Understanding the crypto-asset phenomenon, its risks and measurement issues

Understanding the crypto-asset phenomenon, its risks and measurement issues

Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 5/2019.

This article discusses the crypto-asset phenomenon with a view to understanding its potential risks and enhancing its monitoring. First, it describes the characteristics of the crypto-asset phenomenon, in order to arrive at a clear definition of the scope of monitoring activities. Second, it identifies the primary risks of crypto-assets that warrant continuous monitoring – these risks could affect the stability and efficiency of the financial system and the economy – and outlines the linkages that could cause a risk spillover. Third, the article discusses how, and to what extent, publicly available data allow the identified monitoring needs to be met and, by providing some examples of indicators on market developments, offers insights into selected issues, such as the availability and reliability of data. Finally, it covers selected statistical initiatives that attempt to overcome outstanding challenges.

1 Introduction

The ECB has been analysing the crypto-asset phenomenon with a view to identifying and monitoring potential implications for monetary policy and the risks crypto-assets may pose to the smooth functioning of market infrastructures and payments, as well as for the stability of the financial system.[1] This task begins with the development of a monitoring framework to provide the data and insights that are necessary to continually gauge the extent and materiality of evolving crypto-asset risks with a view to ensuring preparedness for any adverse scenarios.

For its monitoring activities, the ECB relies to a great extent on publicly available third-party aggregated data. A great deal of aggregated information is available on public websites, which can provide, for instance, metrics for crypto-asset networks, estimates of market capitalisation, prices and trading volumes on crypto-exchanges and the amount of funds raised when a crypto-asset is offered to the public in “initial coin offerings” (ICOs). These sources differ with regard to the methodologies they use, the completeness of data coverage and access to the underlying raw information, to name but a few areas. Processing the underlying raw information (when available) brings with it considerable uncertainty about data availability and quality owing, in part, to a lack of regulation of some players along the crypto-asset value chain, whose unsupervised activity in a borderless environment often hinders access to reliable information. Statistics and supervisory reporting mechanisms do not generally cover crypto-assets (e.g. the exposures of supervised institutions to these assets).

Building a crypto-asset monitoring framework on this basis requires caution on account of the data issues, and a stepwise approach to filling gaps. First, it is important to identify monitoring needs based on an accurate characterisation of crypto-assets that allows the scope to be clearly defined. On this basis, once the relevant data sources have been identified, data can be collected and quality checks applied to ensure data quality and the consistency of methodologies and definitions. Whenever possible, the ECB complements aggregated data with granular breakdowns to enable the calculation of customised indicators. Nevertheless, important gaps remain unaddressed in the current framework, such as data on financial institutions’ exposures. Further work is also needed to extract relevant insights from the public networks.

This article is organised as follows. Section 2 describes the characteristics of the crypto-asset phenomenon, in order to arrive at a clear definition of the scope of monitoring activities. Based on this characterisation, Section 3 aims to identify the relevant crypto-asset risks and the economic connections, “gateway” functions and other channels through which these risks may spread to the financial system and the broader economy. Section 4 discusses the indicators for monitoring crypto-assets, based on publicly available data, the availability and reliability of data (including examples based on selected indicators for monitoring market developments), data gaps and ongoing statistical initiatives that attempt to overcome outstanding challenges. Finally, the article offers a number of conclusions and points to the way forward for monitoring crypto-assets.

2 Characterising elements of crypto-assets

The phenomenon of crypto-assets can be defined and analysed from different perspectives, namely their underlying technology, their features and the economic implications that such assets[2] may have. Whereas the use of cryptography is implicit in the choice of the term “crypto”-asset, traditional assets such as money and financial instruments can also be recorded by means of the same technology – typically distributed ledger technology (DLT). Therefore, DLT is not a factor in differentiating the new phenomenon from other assets that are recorded digitally via more traditional technologies. Moreover, the issuer of any digitally recorded asset is, in principle, free to change the technology used for its recording. This implies that the use of DLT as a defining element of crypto-assets would hamper the comparability of data over time and limits its informational content.

To ensure the consistency of its analysis over time and across technologies, the ECB has chosen to define crypto-assets[3] as “a new type of asset recorded in digital form and enabled by the use of cryptography that is not and does not represent a financial claim on, or a liability of, any identifiable entity.” The focus is therefore on the regulatory, economic and business dimension of crypto-assets as a new asset class, rather than on the use of technologies that are currently needed for its existence but are not specific to it. The fact that a crypto-asset does not constitute a claim on any identifiable entity means that its value is supported only by the expectation that other users will be willing to pay for it in the future, rather than by a future cash flow on which users can form their expectations.

The main characterising element of a crypto-asset is that it is not a claim on either an issuer or a custodian. However, its users attach value to it because they believe that: i) its supply will remain limited, and ii) market participants will agree on who is entitled to sell any of the units in circulation. Scarcity of a crypto-asset and the possibility to prove who can dispose of each of its units allow the existence of a crypto-asset market, where users on the supply side can offer their units for sale and users on the demand side are willing to bid.

A trusted bookkeeper would normally support such beliefs by keeping a central record of how many units of an asset have been issued and who holds them at any point in time. Market participants might try to sell units they do not own or to sell units they own a number of times. That can be difficult when dealing with physical goods, whose counterfeiting requires specific skills and physical resources and can typically be vetted by experts, who can differentiate a duplicate from a genuine asset. When an asset is in digital form, counterfeiting is as easy and as cheap as copying and pasting. For this reason, in the case of assets in digital form, a trusted central party is usually tasked with controlling the number of units (notary function) and is responsible for keeping track of who owns what (bookkeeping function).

Cryptographic techniques are used to replace the trusted bookkeeper in the recording of crypto-assets, with a view to: i) ruling out any unexpected increase in crypto-assets issued on a distributed ledger, and ii) getting the network of users to agree on who owns what (further eliminating the need for a trusted bookkeeper). A distributed ledger is essentially a record of information – or database – that is shared across a network of users, eliminating the need for a central party to deal with the validation process. The key innovation brought by DLT is the ability to distribute the validation of the recording of new assets, and of their subsequent transfer, among a set of users who do not necessarily trust one another and may have conflicting incentives. The network of users can be unrestricted and can allow anybody to take part in validation, with no proof of identity required, as is typically the case for crypto-assets. Validation requires a voting process among DLT network users, whose individual voting power depends on the specific protocol used and should prevent the formation of coalitions able to take control of the network.

In the case of unrestricted DLT networks, which are generally used for recording crypto-assets, there is no clear governance. In fact, distributed validation is typically the only governance tool available to agree on who owns what number of units. That hinders the usability of the crypto-asset. To the extent that the validation mechanism aims to prevent a single user (or a relatively small coalition of users) from being able to modify the content and functioning of a distributed ledger, coordinating any change is difficult. Even when a sufficient number of users agree to update the protocol used, other users are free to decide whether to accept the new rules or continue with the old ones. If this happens, a “fork” will emerge, whereby two sets of users rely on different sets of information on individual holdings and may never reconcile their views.

Any asset in digital form can be recorded by means of DLT, without necessarily differing from its non-DLT equivalents in terms of economic impact and legal nature – hence the same regulation could potentially apply. Recording an asset on a distributed ledger does not change its economic characteristics or the set of attached risks that warrant scrutiny by regulators. Assets that constitute a claim on an identifiable entity do not fall under the definition and analysis of crypto-assets in this paper, regardless of the technology used for their bookkeeping. This paper does not therefore cover private financial assets such as financial instruments and funds in the form of electronic money, or commercial bank money. Neither does it cover central bank money in the form of banks’ reserves, cash, or the widely researched but yet theoretical concept of a central bank digital currency.

3 Crypto-asset risks and linkages that warrant monitoring

The financial system may be subject to risks from crypto-assets to the extent that both are interconnected; spillover effects may also be transmitted to the real economy. In particular, crypto-assets may have implications for financial stability and interfere with the functioning of payments and market infrastructures, as well as implications for monetary policy. ECB analysis[4] shows that, while these risks are currently contained and/or manageable within the existing regulatory and oversight frameworks, links with the regulated financial sector may develop and increase over time and have future implications. The discharge of the Eurosystem’s responsibilities, namely to define and implement monetary policy and to promote the smooth operation of payment systems, as well as the Eurosystem’s tasks in the areas of banking supervision and financial stability, may be affected. Accordingly, the analysis concludes that the ECB should continue monitoring crypto-assets, raise awareness of their risks and develop preparedness for any future adverse scenario. This section aims to: i) provide an overview of risks stemming from crypto-assets, and ii) identify the main connections that may facilitate the transmission of these risks to the financial system and the economy, with a view to informing and calibrating monitoring efforts.

Crypto-asset risks primarily originate from: i) the lack of an underlying claim, ii) their (partially) unregulated nature, and iii) the absence of a formal governance structure.

i) Since crypto-assets have no underlying claim, such as the right to a future cash flow or to discharge any payment obligation, they lack fundamental value. This makes their valuation difficult and subject to speculation. As a result, crypto-assets may experience extreme price movements (volatility risk), thereby exposing their holders to potentially large losses. Depending on the circumstances of a possible price crash, the effects may be passed on to the creditors of the holders (if the positions involve leverage) and other entities.

ii) Crypto-assets, as defined in this article, can hardly fulfil the characteristics of payment and financial instruments[5] and, as such, fall outside the scope of current regulation.[6] Given that they are unregulated, their holders do not benefit from the legal protection associated with regulated instruments. For instance, in the event of bankruptcy or hacking of a crypto-asset service provider that controls access to customers’ holdings of crypto-assets (e.g. custodian wallet providers), the holdings would neither be subject to preventive measures (e.g. safeguarding and segregation) nor benefit from schemes or other arrangements to cover any losses incurred. In view of the current state of law, there is limited scope for public authorities to regulate crypto-assets.[7] Any such intervention may be further complicated by the lack of governance and distributed architecture of crypto-assets (see below), as well as their cross-border dimension.

iii) As the use of DLT allows crypto-assets to dispense with an accountable party, the roles and responsibilities for identifying, mitigating and managing the risks borne in the crypto-asset network cannot be (clearly) allocated. From this characteristic derive, among others, heightened money laundering and terrorist financing risks, to the extent that there is no central oversight body responsible for monitoring and identifying suspicious transaction patterns, nor can law enforcement agencies target one central location or entity (administrator) for investigative purposes or asset seizure.[8] In view of the lack of formalised governance, it may also be difficult to address operational risks, including cyber security risks, and the risk of fraud. In fact, in the broader crypto-asset ecosystem, the provision of certain services (e.g. trading) is often centralised. In such cases, the service providers can be identified and held accountable. However, this is not always possible in decentralised models, which minimise or do away with the role of intermediaries.

The extent to which the financial system and the economy may be exposed to crypto-asset risks depends on their interconnectedness. In particular, i) holdings of crypto-assets, ii) investment vehicles, and iii) retail payments represent the main linkages between the crypto-asset market on the one hand and the financial systems and the broader economy on the other hand.

i) Individuals and financial institutions, including credit institutions/investment firms, payment institutions and e-money institutions, are not prohibited by EU law from holding or investing in crypto-assets.[9] Crypto-assets can be accessed by anyone with an internet connection, with no need to open an account with a crypto-asset service provider. Financial institutions may invest in crypto-assets and/or engage in trading and market making activities. Credit institutions may also provide credit to clients to acquire crypto-assets or loans collateralised with crypto-assets, as well as lend to entities that deal with crypto-assets. Moreover, financial institutions can provide other crypto-asset-related services (e.g. custody services) that may result in enhancing the accessibility and fostering the use of crypto-assets, thereby incentivising crypto-asset holdings and investments. These activities may be motivated, among other things, by financial institutions’ interest in applications relying on DLT.

ii) Derivatives and investment vehicles connect investors with the crypto-asset market without them having to hold crypto-assets directly. Investment vehicles include exchange-traded products (ETPs) and contracts for difference (CFDs) that track crypto-asset prices. In addition, ICOs – a largely unregulated way for firms to raise capital by generating new crypto-assets in a way similar to initial public offerings – have started to raise interest among investors since 2017, motivated by high returns on investment. It should be noted, though, that these “coins” may vary significantly in terms of their characteristics and functions: for instance, they may offer forms of investment in a company that may be linked to securities, or merely grant access to (future) products/services offered by the issuer. Suffice it to say, for our purposes, that these “coins” may not qualify as crypto-assets as defined in Section 2, to the extent that they have an issuer.

iii) Under certain circumstances, crypto-assets may be used for retail payments. Use cases range from merchant payments, international remittances and business-to-business (B2B) cross-border payments, to micro-payments and machine-to-machine (M2M) payments,[10] and may be driven by DLT-driven efficiency gains as these segments are generally characterised by complexities and high costs. It should be noted that, while holders of crypto-assets can transfer crypto-asset units without an intermediary by accessing directly the decentralised crypto-asset network, user convenience has led to the emergence of service providers that facilitate the use of crypto-assets for payments, e.g. by handling payments on behalf of merchants that accept crypto-assets and by reducing their exposure to price volatility. Often, though, end-users still make and/or receive payments in national currency(ies) and are not required to hold crypto-asset balances, whereas the role of crypto-assets is limited to enabling a back-end channel for the transaction, particularly in cross-border payments.[11]

New and existing intermediaries provide the “gateway” functions that facilitate the interconnections between crypto-assets on the one hand and the economy and financial markets on the other hand. Within the broader crypto-asset-related activities, gateway functions describe the activities that enable the inflows and outflows of crypto-assets from the crypto-asset market to the financial systems and the economy, i.e. crypto-asset trading and custody/storage. Other functions (e.g. mining) or services (e.g. promotion of ICOs) are out of scope, because they live exclusively within the crypto-asset ecosystem. Payment services, in turn, rely on the gateway functions to foster the use of crypto-assets as a means of exchange.

Trading platforms provide the on-off ramps for users to buy and sell crypto-assets[12] in exchange for either fiat currencies or other crypto-assets. Trading platforms may differ in their business models and the services they provide. Some trading platforms may publish market quotes based on their clients’ trading activity and, by doing so, facilitate price formation. Trading platforms may also be distinguished based on whether or not they hold crypto-assets on behalf of their clients, and execute trades on their books as opposed to the DLT network(s). Some centralised platforms may provide custody services beyond what is needed to execute/settle a trade, in which case they also act as custodian wallet providers (see below) on a permanent basis.

Custodian wallet providers allow the storage of cryptographic keys that are used to sign crypto-asset transactions. The involvement of a custodian wallet provider is generally requested by crypto-asset investors because of its convenience and on the premise that cryptographic keys will be stolen less easily than from a personal device. Custodian wallets can be either hosted online (also called “hot wallets”, entailing the storage of keys on a device that is connected to the internet that allows the initialisation of transactions at any time) or offline (also called “cold wallets”, entailing the storage of keys with no connection to the internet until the user needs to authorise a transaction). Hot wallets are vulnerable to hacking via the internet. Cold wallets, on the other hand, are less convenient to use frequently but are protected from hackers and can also be kept in devices that can be physically locked in vaults. In some cases, the custodian directly holds the crypto-asset units via its cryptographic key on behalf of the investor.

The size and extent of the interconnections and gateways described above may have implications for the stability of the financial system, monetary policy and the safety and efficiency of payments and market infrastructures:[13]

- Potentially large and unhedged exposures of financial institutions to crypto-assets could have financial stability implications, all the more so since there is currently no identified prudential treatment for crypto-asset exposures of financial institutions. In its statement on crypto-assets, while conceding that banks currently have very limited direct exposures, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) sets expectations for banks that acquire crypto-asset exposures or provide related services, including due diligence, governance and risk management, disclosure and supervisory dialogue.[14] The European Banking Authority (EBA) also foresees the development of a monitoring template that competent authorities can issue to financial institutions to identify and measure the level and type of crypto-asset activity.[15]

- In an extreme scenario, if euro cash and electronic payment instruments hypothetically gave way to crypto-assets for retail payment transactions, there could be significant implications for monetary policy and economic activity.[16] However, given the characteristics of the crypto-asset phenomenon, particularly high price volatility, it is difficult to envisage crypto-assets fulfilling the role of a monetary asset in the near future. Having said that, new developments aiming to mitigate volatility risks (i.e. “stablecoins”) may prove more attractive or suitable for payment use cases.

- Finally, financial market infrastructures (FMIs), particularly payment systems, securities settlement systems and central counterparties, carry the risks of crypto-assets and may act as channels for the transmission of these risks through the financial system. First, financial market infrastructures may be exposed to risks from their participants’ crypto-asset activities to the extent that adverse crypto-asset market conditions or other adverse events may compromise participants’ ability to meet their obligations. In this case, crypto-asset market-based shocks could be passed from one participant or infrastructure to another/others. Second, financial market infrastructures may pose risks if they clear crypto-asset-based products or use crypto-assets for settlement, collateral or investment. As it currently stands, European law effectively limits the usage of crypto-assets as settlement assets in financial market infrastructures and sets requirements for collateral or investments that crypto-assets do not currently meet.[17] Moreover, for EU central counterparties to clear crypto-asset products, they would need to obtain authorisation from their national authorities subject to demonstrating how risk management requirements were to be fulfilled in the light of the specific characteristics to be addressed.

4 Current issues in measuring the crypto-asset phenomenon

To properly assess crypto-asset risks and their potential impact on the financial system and the economy, it is necessary to complement the qualitative analysis on the linkages described (see Section 3) with quantitative information. On the one hand, the public nature of crypto-asset DLT networks generally ensures transparency, i.e. transaction data are open for the public to see and verify. On the other hand, the decentralised and (partially) unregulated nature of crypto-asset activities makes it difficult to obtain specific data (e.g. the number of individual users) and to organise systematic data collection efforts. In this context, public websites that track crypto-asset prices only provide a rough indication of market trends. Overall, available data on crypto-assets are neither complete nor fully reliable for the purposes of monitoring market trends to the degree of detail necessary to gauge their risks. Moreover, they only allow the monitoring of global trends with very limited country segregation. This section will discuss the current shortcomings in data collection and analysis, providing concrete examples, and will propose possible options to overcome major constraints.

4.1 Stepwise approach to the monitoring framework of crypto-assets

Publicly available aggregated data already provide some tools for measuring crypto-asset risks and their linkages with the regulated financial system. These data, subject to passing quality checks and being complemented with other data from commercial sources, provided the basis of a crypto-asset dataset as the first step in the ECB approach to monitoring this phenomenon. Using application programming interfaces (APIs)[18] and big data technologies, it has been possible to create an automated set of procedures for collecting, handling and integrating several data collections with a view to deriving customised indicators. The ECB collected data from publicly available and commercial data providers considering available documentation, coverage and the availability of very granular aggregates or raw data. The granularity of data, coupled with applied data quality control measures, enabled the calculation of customised and methodologically consistent indicators. Preparing consistent indicators required the development of mappings and the harmonisation of information.[19]

Crypto-asset indicators tailored to this monitoring exercise have been grouped in four categories covering i) markets, ii) gatekeepers, iii) linkages, and iv) ICOs.

i) Market indicators cover pricing and trading information, including derivatives markets. The monitoring tool allows selecting any crypto-asset or a group of crypto-assets from a pool of over 2,000 assets currently traded and constructing indicators on prices, traded volumes and market capitalisation in selected units of fiat or crypto-assets. Furthermore, it includes indicators focusing on trading vis-à-vis fiat currencies. With respect to derivatives, the indicators offer a detailed overview of bitcoin futures contracts traded on the institutionalised exchanges of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) and the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE).

ii) The indicators on gatekeepers cover trading platforms and wallets, as well include some information on payments. The indicators on trading platforms show trading volumes and pricing by selected platform or a set of platforms grouped according to their country of incorporation, fees option, centralisation or decentralisation feature and other factors. Additionally, indicators on arbitrage have been developed. With respect to wallets, information on the classification of wallets by type, supported crypto-assets and security features are collected. The payment segment contains indicators on the number and locations of ATMs supporting crypto-assets, which are those that enable the user to buy and sell a particular crypto-asset against fiat currencies. Moreover, some information on cards supporting crypto-assets is included. Such cards enable payment in fiat currencies using crypto-assets as a deposit. Furthermore, some indicators based on on-chain transactions are provided.

iii) An important category of indicators aims to cover to the extent possible the linkages of the crypto-asset markets with the financial systems and the real sector of the economy. The indicators from this category cover for example ETPs offering exposures to crypto-assets and indicators based on statistics on holdings of securities[20].

iv) The final part concerns the indicators for ICOs, i.e. amount of funds raised and features, e.g. their legal form, the underlying blockchain and the country of incorporation.

However, there are still important gaps in the data, particularly relating to certain interlinkages and to payment transactions, including the use of layered protocols (see Section 4.2). First, a major data gap exists with respect to the interlinkages with the real and financial sectors, including the amount of banks’ or financial corporations’ direct holdings of crypto-assets and information on lending for purposes of investing in crypto-assets. Another area concerns transactions with cards supporting crypto-assets, sales of merchants accepting crypto-assets and the value of withdrawal transactions from crypto-asset ATMs. Finally, an analysis of the information on transactions using layered protocols is required to capture the actual extent of the use of crypto-asset DLT networks for settlements. The dataset for the crypto-asset monitoring framework is, by definition, a constantly evolving product, as it has to keep up with changing monitoring needs, reflecting rapid changes in the market, while remaining proportionate to the potential risks posed by the crypto-asset market.

As a second step in the development of a monitoring framework for crypto-assets, it is envisaged that major data gaps should be closed. Overall, the first step in the data processing cycle has been completed, paving the way for the next steps covering further work on indicators and data, which would close the identified data gaps. Actions derived from feedback from this data processing cycle are expected to enhance the data and analytical infrastructure. Work will continue to further develop the indicators based on the granular data from trading platforms, blockchains and official data collections and statistics on the crypto-asset market, consistent with the monitoring needs and proportionate to the potential risks posed by this market.

4.2 Availability and reliability of data on on-chain, off-chain and layered protocol transactions

To assess the availability and reliability of data on crypto-assets, it is important to differentiate between “on-chain” and “off-chain” crypto-asset transactions. On-chain crypto-asset transactions are those recorded directly on a distributed ledger. Off-chain transactions are recorded either on the book of an institution, for instance in the case of trading platforms, or in a private network of users that use the distributed ledger of a crypto-asset to record the net transactions among participants only at a later stage.

On-chain transactions

Information concerning on-chain data is often publicly available, although its analysis can be complex. Most DLT protocols differ from the record-keeping that is typical of financial accounts systems, where an amount of an asset is transferred by reducing the sender’s account by that precise amount and by crediting it to the receiver’s account. Crypto-assets are usually transferred in a way similar to that of cash transactions: when a user receives a quantity of crypto-assets, those units are not divisible and have to be sent all together in a future transaction.[21] Therefore, a sender needs to specify what part of the crypto-asset units jointly obtained in a previous transaction should be transferred to the receiver(s) and what part should come back as “change”.

Identifying the value of a crypto-asset transaction and whether different crypto-asset wallets belong to the same individual (or institution) is currently a difficult task. However, it is likely to become even more challenging in the future. Change can either be allocated to the same wallet from which the transaction originated or be routed to another wallet controlled by the sender.[22] A number of initiatives are being developed by the community of crypto-asset users to make identification of these transactions more difficult. Such initiatives include the possibility of a number of senders combining their crypto-asset transactions.[23]

On-chain data recorded on the distributed ledger of a crypto-asset can refer to transactions in other assets, which are recorded and transferred by means of an associated layered protocol. While the distributed ledger is typically used to record only one “native” crypto-asset, its transactions can be used to record free-form text. Concretely, this text can contain the confirmation that other assets have been transferred using a distinct protocol.[24] Since a superficial analysis of the on-chain transaction would only disclose a negligible transaction in the native crypto-asset, one needs to interpret the transaction knowing the details of the layered protocol in order to conclude that possibly a sizeable transaction has occurred in the second asset.

Off-chain transactions

Various methodological choices are applied in constructing and supplying the very rudimentary information of the price and market capitalisation of a crypto-asset. In general terms, the aggregated price information of a crypto-asset is determined, among other things, by the selection of trading platforms, the underlying trading volumes, conventions concerning the 24-hour close-of-business time, factors to address low liquidity levels, failures of trading platforms, data and connectivity. Without applying any selection criteria, pricing of crypto-assets is very disperse.[25] Pricing information feeds further into the calculation of the market capitalisation indicator, together with the crypto-asset supply information for which various options exist.

Off-chain transactions are a growing phenomenon that aims to overcome the constraints of distributed ledgers used for crypto-assets. In an unrestricted DLT network, the validation of new transactions has to be costly to preserve the integrity of the system and relatively slow to allow sufficient time for all users to agree on the latest valid set of transactions before a new one is validated. “Channels” have been introduced as a solution for clusters of users to settle transactions faster among themselves and, as in net deferred settlement typical of some market infrastructures, only use the unrestricted distributed ledger for the “ultimate” settlement of net transactions.

Pricing and trading information

Even when a business related to crypto-assets is covered by regulation, as should be the case with crypto-asset trading platforms, there are instances where no accountable party takes the role of operator. This is true of some trading platforms that are “decentralised”, since they rely on validation by DLT network users to execute a trade. Moreover, trades agreed on decentralised trading platforms typically involve the mutual transfer of two assets, which are settled as two individual transactions that can hardly be identified as constituting a single trade.

One of the main differentiating factors with respect to trading activities and the resulting pricing are the fee characteristics of crypto trading platforms. Among trading platforms, those with zero-fee or transaction-fee mining features might be problematic in the context of pricing and trading volume data reliability. On zero-fee platforms, traders are able to trade freely without fees, regardless of how many trades they make, which may lead to higher trading volumes. Similarly, trading platforms with a transaction-fee mining feature offset transaction fees with trading platform native tokens. A reward of this nature might incentivise traders to trade more to receive tokens that offer valuable options as voting rights on the platform or a dividend. Both of these forms can lead to market manipulation of simultaneously selling and buying the same asset to create misleading and artificial market activity, also called wash trading.

Low liquidity, unusual price spikes and erratic trading behaviour in the round-the-clock market also contribute to the challenges of pricing crypto-assets. Unlike any other market, the crypto-asset market operates 24 hours per day, with no standardised “close of business” time. Data aggregators provide lower frequency data, e.g. daily, in line with their preferred time frame convention, which may not coincide with that of other providers. To address the issue of low liquidity, data providers adjust the contributions of the prices achieved on the less liquid exchanges in the overall indicator of a price of a crypto-asset. Unusual spikes and erratic trading behaviour are also corrected using boundaries or other exclusion criteria based on benchmarks supported by, for example, website traffic indicators and expert judgement. The issue contributing to the difficulty in getting reliable data covers also the lack of standard naming convention for crypto-assets and their identifiers.

The uninterrupted provision of data by trading platforms might be affected by technical issues related to the substantial risks of cyberattack, fraud and hacking.[26] In cyberattacks, such as denial-of-service attacks, the perpetrators seek to make a machine or network resource unavailable to its intended users by disrupting the service of a host connected to the internet. This is typically accomplished by flooding the targeted machine or resource with requests. The hacking of user or platform accounts may lead to the bankruptcy of trading platforms, especially those with unsuitable technological infrastructures operating in a legally uncertain global virtual environment. Theft, cybercrime and other criminal activities have affected an estimated 6% of the total supply of bitcoin and do not include the unreported cases of individuals who have lost bitcoins to hackers. With respect to the interruption of data provision, typical issues that data aggregators or exchanges experience take the form of service outages, connectivity errors and unstable APIs.

Market capitalisation information

In order to calculate market capitalisation the price of a crypto-asset has to be complemented with information on the aggregate supply, which can be measured in several ways. Specifically, four main measures of supply can be distinguished: i) circulating supply, ii) total supply, iii) maximum supply, and iv) variations of inflation-adjusted supply, which take into account future supply within a specific time horizon (usually five years). Circulating supply is the best approximation of the units of a crypto-asset that are circulating in the market or are in the hands of the general public. Total supply is the total number of units of a crypto-asset in existence at a given moment in time. In addition to circulating supply, total supply includes those units that are locked, reserved or cannot be sold on the public markets and excludes units that have been verifiably burned. Maximum supply is the approximation of the maximum amount of units that will ever exist in the lifetime of this crypto-asset and is pre-determined by the protocol used. In the case of inflation-adjusted supply, an additional supply scheduled, for example, for the next five years is added to the circulating supply. Finally, for some crypto-assets, maximum supply does not exist, as there is no limit implied by the protocol.

Bitcoin futures and crypto-asset exchange-traded products in Europe

Information provided by reliable sources, such as institutionalised exchanges trading bitcoin futures or ETPs, may not be fully comparable due to differences in the specifications of the underlying contracts or investment pools. Bitcoin futures are traded on trading platforms, such as BitMEX and BitflyerFX, as well as on the institutionalised exchanges, i.e. CBOE and CME. Bitcoin futures on the institutionalised exchanges differ with respect to contract units, price limits, margin rates and tick sizes, thereby rendering the prices quoted by the two exchanges not strictly comparable.[27] Further differences stem from different settlement bases and underlying cut-off times.[28] ETPs traded on the institutionalised exchanges, for instance the SIX Swiss Exchange[29] or Nasdaq Nordic[30] in Europe, offer exposures to bitcoin and Ethereum and are priced based on various sources.[31]

Aggregated indicators on crypto-assets

A wide variety of indicators aims to represent the total market of crypto-assets. These indicators are provided on the internet either by commercial[32] or non-commercial websites, which supply crypto-asset-related information, funds investing in crypto-assets,[33] or research groups[34] and academics.[35] For such indicators, the most important methodological choices include the coverage of crypto-assets and pricing sources, index rebalancing and weighting schemes. With respect to the selection of crypto-assets, market capitalisation is the main criterion used. Pricing sources are selected based on their liquidity, reliability and fulfilment of various selection criteria, e.g. compliance with anti-money laundering policies. Weighting schemes are also based on market capitalisation, often applying caps and trading volumes. Rebalancing is carried out periodically, typically on a monthly frequency, but can also be in close to real time.

Summing up, two aspects for future work emerge from the analysis of issues concerning measuring the crypto-asset phenomenon. The first is to deal with the complexity and growing challenges of analysing on-chain and layered protocol transactions. With respect to off-chain transactions, given the many methodological options, further analysis should focus on increasing the availability and transparency of the reported data and the methodologies used, harmonising and enriching metadata, and developing best practices for indicators on crypto-assets.

4.3 Selected measurement issues with rudimentary indicators of crypto-asset market developments

While one of the basic indicators of the size of the crypto-asset market that is often used is the growing number of crypto-assets created over time, only a fraction of these crypto-assets is traded persistently. Out of the thousands of crypto-assets created so far, around 35% have been recently traded on trading platforms (see Chart 1) and 5% have been traded every day since the beginning of 2018. Similar developments can also be observed when looking at the indicator of the number of trading pairs. The number of crypto-assets traded on a daily basis (i.e. within 24-hour intervals) recovered from lows of around 1,300 at the turn of 2018 and 2019 to reach just over 2,200 in April 2019. April 2019 numbers are relatively close to the record high of 2,456 crypto-assets traded on a daily basis, recorded in September 2018. From a trading persistency perspective, around 700 crypto-assets have been traded every day since the beginning of 2019, one-third of them since the beginning of 2018. In terms of trading pairs, recent numbers point to more than 5,100 pairs traded on a daily basis, up from the 3,000 pairs traded in the first quarter of 2019. Every day since the beginning of 2019, 1,603 pairs have been traded, one-third of this amount since the beginning of 2018.

Chart 1

Traded crypto-assets

(April 2019; thousands)

Sources: Cryptocompare and ECB calculations.

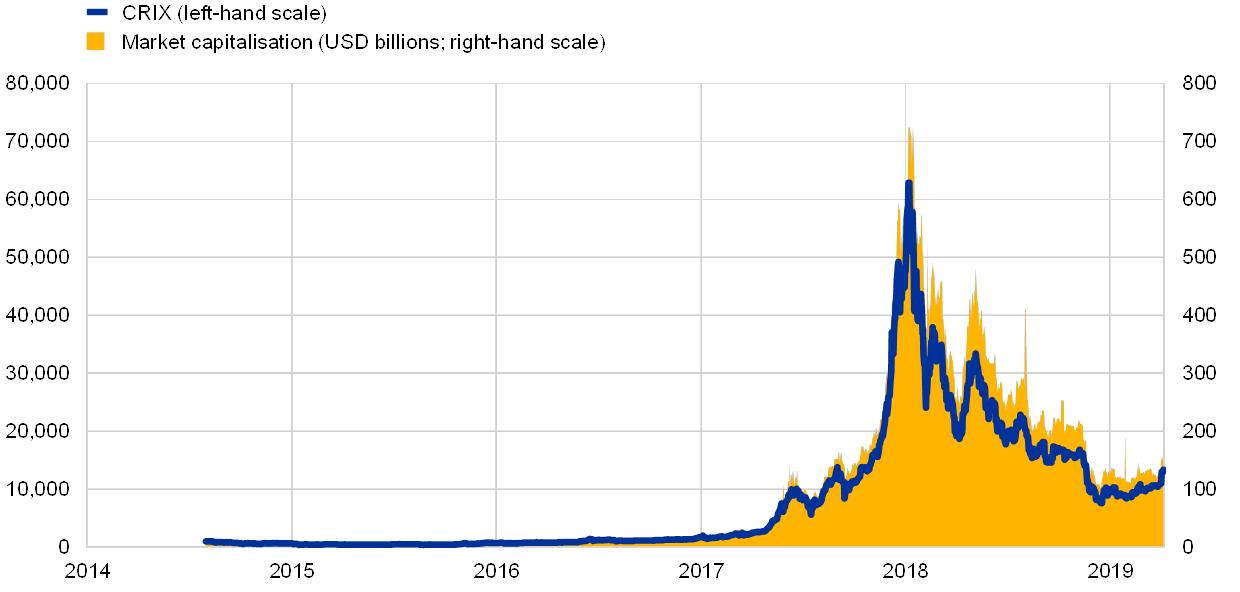

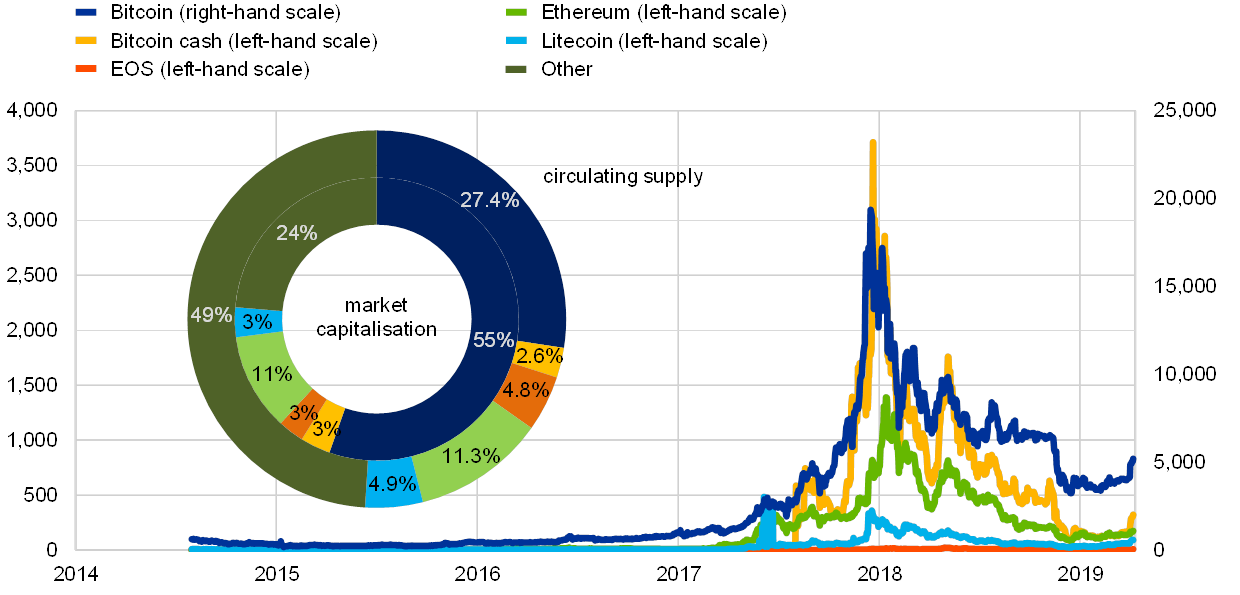

If another indicator, market capitalisation, is used for gauging the size of the crypto-asset market, the size varies by 20%, depending on whether the circulating supply or the maximum supply is chosen as the underlying measure. Recent market capitalisation based on the circulating supply (estimated at USD 165 billion) has returned to 2017 levels, having peaked at the end of 2018, strongly mirroring developments in the pricing of crypto-assets as measured, for example, by the CRIX index[36] (see Chart 2). Three-quarters of the total market capitalisation is accounted for by five crypto-assets, which also make up half of the total circulating supply of crypto-assets (see Chart 3). Market capitalisation of bitcoin alone constitutes 50% of the total, while its total circulating supply amounts to slightly less than one-third of the total for crypto-assets. Prices of these five crypto-assets strongly shaped the general pricing trends of the total crypto-asset markets. Using the maximum supply of crypto-assets to calculate the market capitalisation would mean a 20% increase in the indicator value, with half of this attributed to bitcoin. In line with the bitcoin protocol, the maximum supply of bitcoin would be reached in 2140.

Chart 2

Market capitalisation and crypto-asset price index

(April 2019)

Sources: Cryptocompare, CRIX, Coinmarketcap and ECB calculations.

Note: Market capitalisation is based on the circulating supply.

Chart 3

Prices, market capitalisation and circulating supply of selected crypto-assets

(April 2019; USD)

Sources: Cryptocompare, Coinmarketcap and ECB calculations.

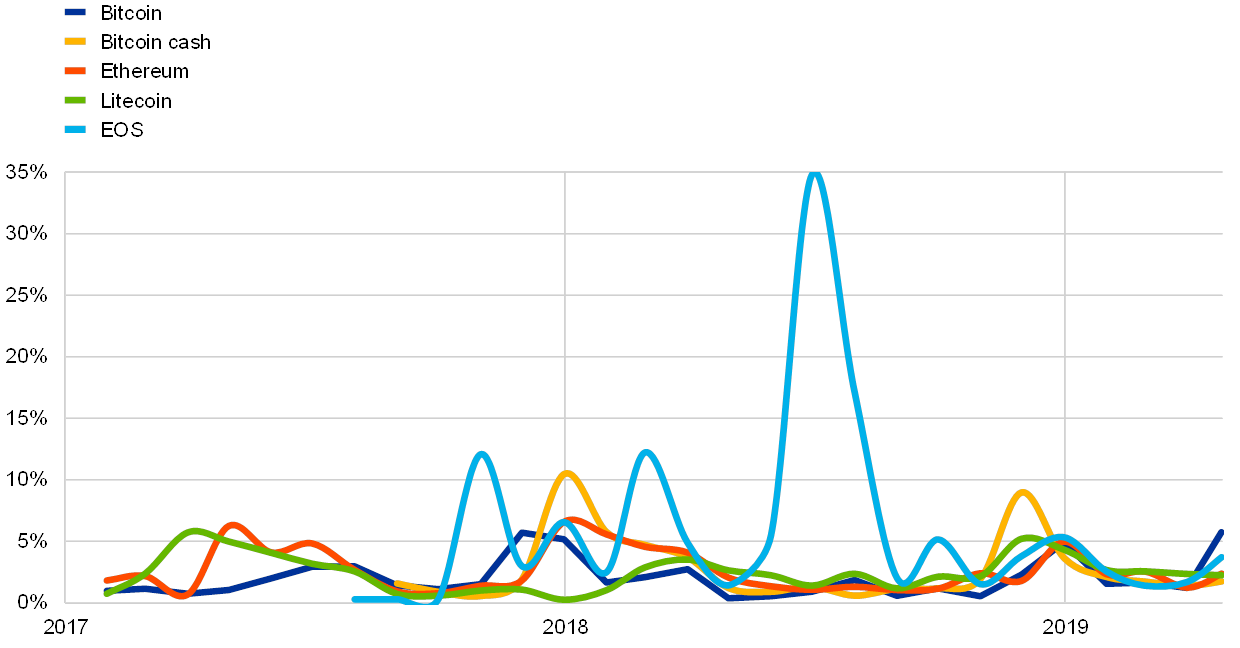

The total market pricing and market capitalisation trends were strongly shaped by the aggregate prices of each of the five aforementioned crypto-assets, which on a disaggregated basis fluctuated significantly across trading platforms. Disregarding differences in the trading and transaction fees of various platforms, as well as transaction processing times and potential price movements between transactions, the price heterogeneity for crypto-assets is significant (see Chart 4). The normalised interquartile ranges of the prices of five major crypto-assets traded versus the US dollar picked up in April 2019, although they did not reach end-2018 levels of around 5% and 9% (the latter for bitcoin cash). The dispersion of the prices of each of these crypto-assets across trading platforms have decreased in 2019, compared with 2018 levels and peaks around the turn of the year.

Chart 4

Price dispersion for selected crypto-assets

(April 2019)

Sources: Cryptocompare and ECB calculations.

Note: The interquartile ranges of prices of crypto-assets across trading platforms are normalised by the average price across platforms weighted by trading volumes.

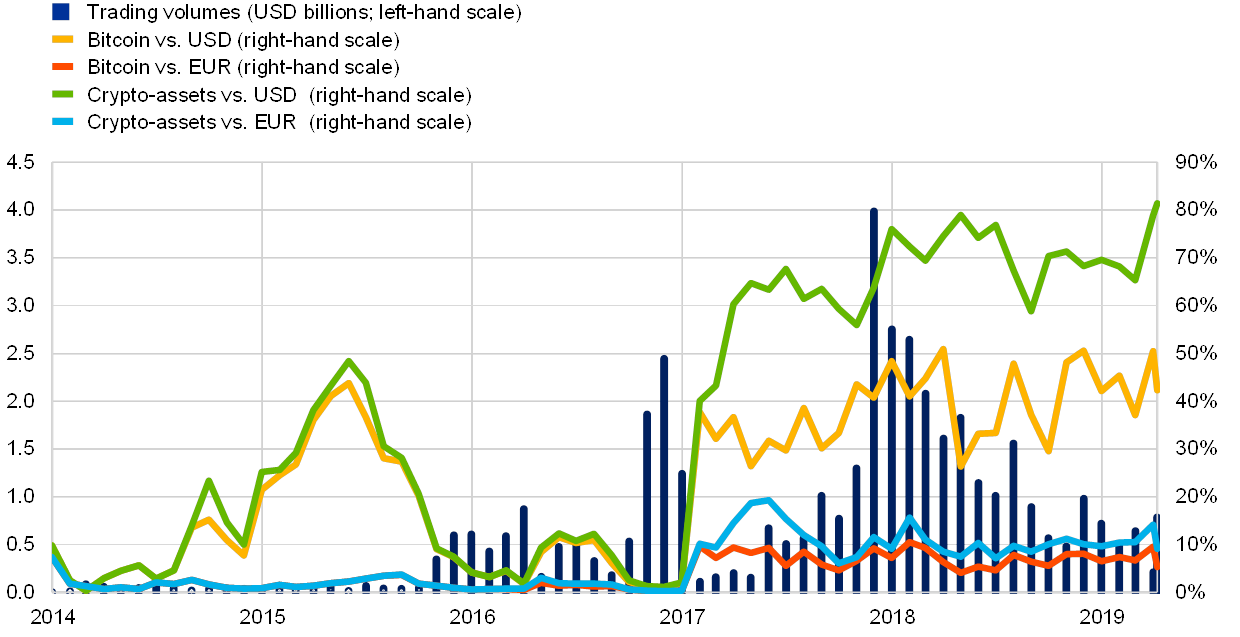

Trading activity vis-à-vis fiat currencies on the crypto-asset platforms has remained buoyant, albeit at lower levels historically, while wash trading is considered to be significant. From the central bank perspective, it is important to monitor the volumes of crypto-assets that are cleared in euro and in other fiat currencies. Trades of crypto-assets cleared in euro hovered broadly around 10% of all trades vis-à-vis fiat currencies, compared with an increasing share of up to 81% for the US dollar. Half of the volumes vis-à-vis fiat currencies were recorded for bitcoin. The trades took place, by and large, on centralised trading platforms. However, activity on decentralised trading platforms seems to be picking up but still accounts for less than 1% of trading volumes. From the geographical perspective, trades on platforms located in Europe amounted to 24% of all trading, with the highest trading volumes recorded on platforms in Malta and the United Kingdom, while trades on platforms not attributed to a country accounted for 30% of trading volumes. With respect to wash trading, some analyses[37] point to the very high number of trades affected by this market manipulation.

Chart 5

Trading volumes vis-à-vis USD, euro and other fiat currencies

(April 2019)

Sources: Cryptocompare and ECB calculations.

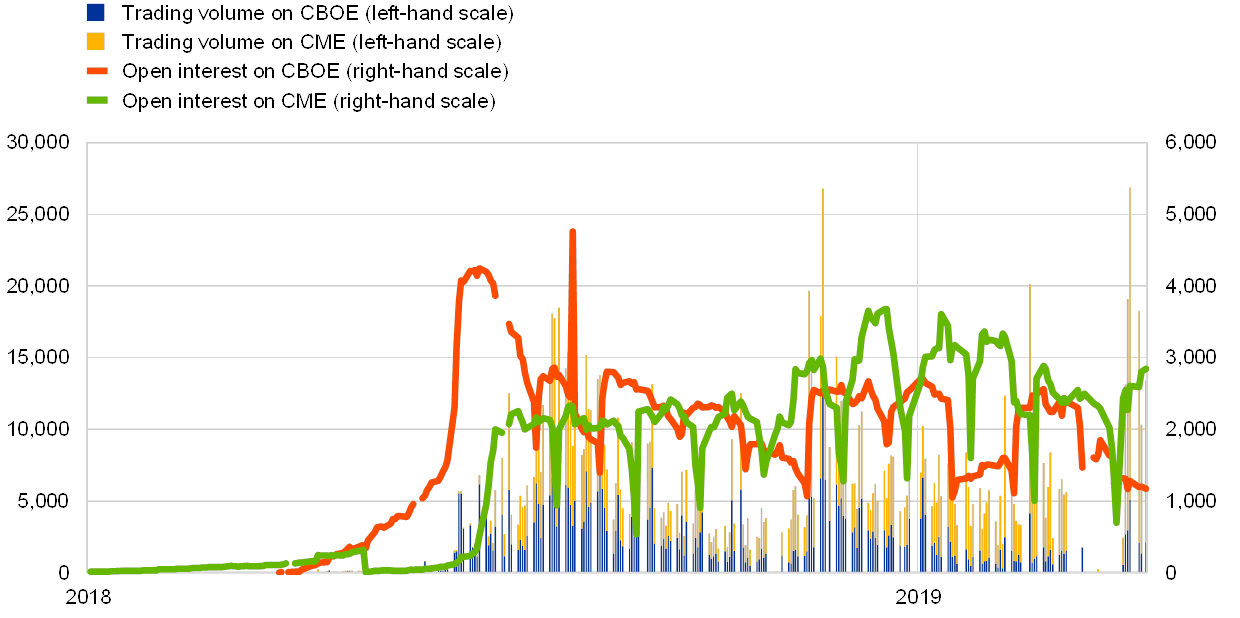

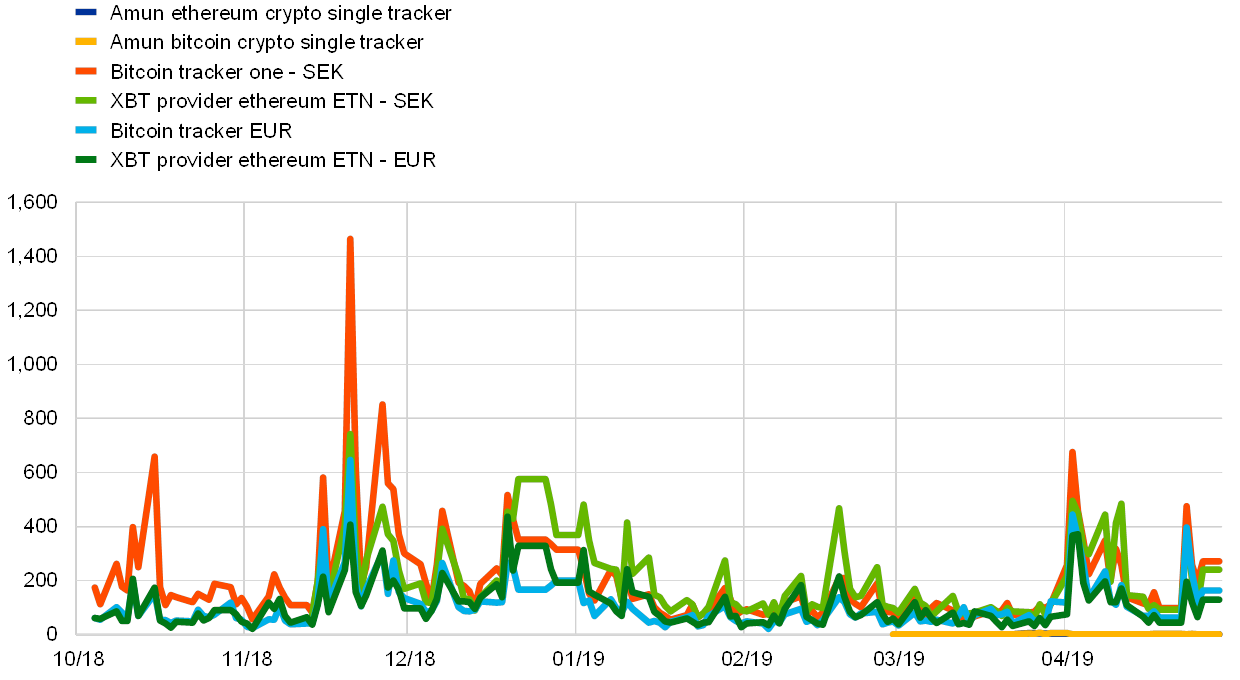

On institutionalised exchanges, trading activity of bitcoin futures and ETPs with underlying crypto-assets peaked in April 2019; however, CBOE suspended trading of bitcoin futures, while trading activity of ETPs on the SIX Swiss Exchange is anaemic. The bitcoin futures market has declined slightly since the end of 2018. Trading volumes peaked strongly, though, on the CME exchange in April 2019, following the CBOE announcement of the suspension of the upcoming future contracts, citing improvements in the approach towards crypto-currency derivatives as a reason (see Chart 6). Turning to trading activity for ETPs on European exchanges, as measured by the number of trades, while activity is buoyant on the Nasdaq Nordic, reaching more than 17,000 trades in April, trading on the SIX Swiss Exchange is weak (see Chart 7).

Chart 6

Trading volumes and open interest of bitcoin futures

(April 2019)

Sources: Bloomberg and ECB calculations.

Note: Trading volumes and open interest refer to the current contracts for the forthcoming month.

Chart 7

Trades of ETPs on the European institutionalised exchanges

(April 2019; number of trades)

Sources: Bloomberg and ECB calculations.

While no hard data are available for purchase transactions of goods or services with settlement in crypto-assets, some indicators on the usage of crypto-assets point to activity picking up slightly. This is reflected in the growing number of ATMs supporting crypto-assets, an increase in the options of cards with crypto-asset features, new wallets with expanded coverage of crypto-assets and a growing interest by merchants in accepting crypto-assets. The number of ATMs supporting crypto-assets is growing, with the largest numbers in the United States and Canada (2,643 and 625 respectively). The number of similar ATMs in Europe is approaching 1,000, which constitutes a 20% share of these ATMs worldwide, the biggest presence being in the United Kingdom and Spain. With respect to cards supporting crypto-assets, there are a few new options of cards in Europe that can be loaded with major crypto-assets, e.g. bitcoin, Ethereum or litecoin. Regarding wallets, the majority are targeting the major crypto-assets and are becoming more multi-asset-oriented, with some supporting close to 100 crypto-assets. For the majority of wallets, users control their private keys as opposed to the less popular options of storing private keys with a third party. Despite the reportedly growing interest of merchants in accepting crypto-assets as a form of payment,[38] no hard data on underlying transactions are available. However, purchase transactions of goods or services with settlement in crypto-assets in Europe are estimated to be insignificant.

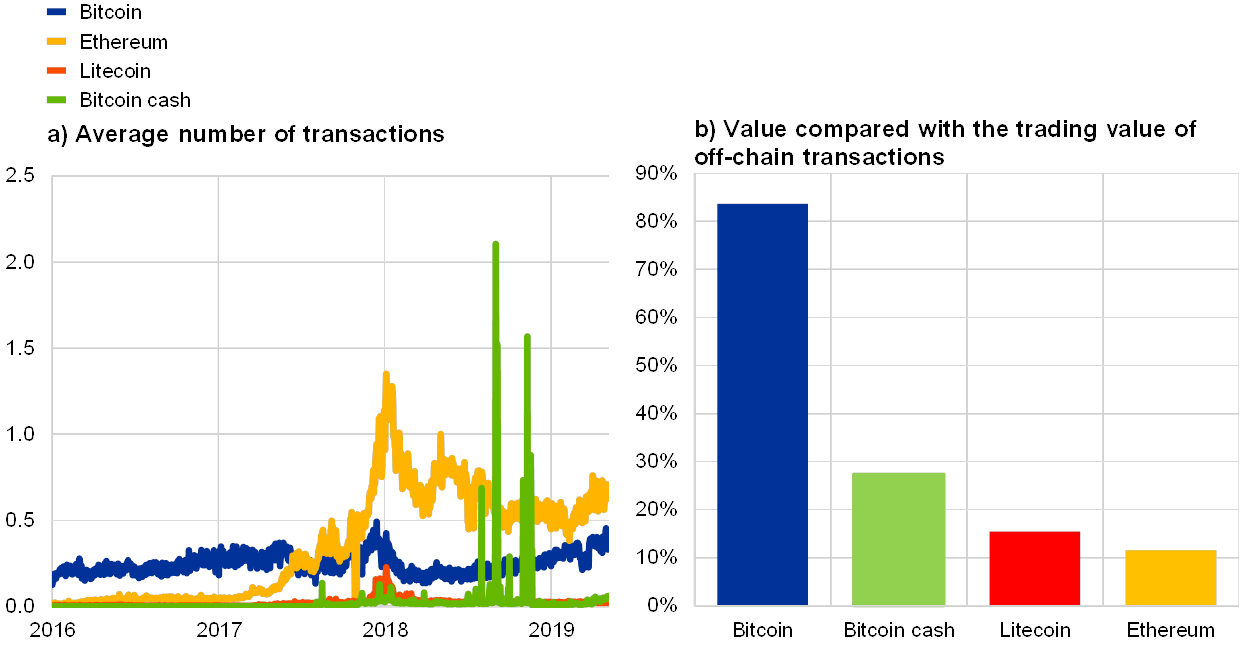

The number of on-chain transactions for major crypto-assets is growing, but it only gives a partial view of total crypto-asset transactions as off-chain transactions are not taken into account. The number of transactions per day on the bitcoin blockchain shows a steady increase since spring 2018. Transactions on the Ethereum blockchain are currently at the 0.5 million level, after peaking in January 2018 at 1.3 million per day. Transactions on the bitcoin cash blockchain recently showed an upward trend, from 4,000 to 38,000 transactions per day. This followed a few extreme spikes in winter 2018 after the split of this crypto-asset. Finally, transactions on the litecoin blockchain remained rather stable at around 25,000 transactions per day. Comparing the values of the transactions recorded on these blockchains with the trading values on trading platforms, the on-chain transactions account for a small fraction of the value of off-chain transactions (see Chart 8).

Chart 8

On-chain transactions for selected crypto-assets

(April 2019; left panel: millions/day; right panel: percentages)

Sources: Bitinfocharts, Cryptocompare and ECB calculations.

Overall, selected indicators show that the crypto-asset market is resilient, but analysis should be interpreted with caution on account of uncertainties related especially to significant price dispersion, wash trading and the unavailability of hard transaction data. Despite the broad decline in the off-chain prices of crypto-assets, following a peak at the end of 2018, in the crypto-asset market a high number of crypto-assets continue to be traded every day on the trading platforms and activity is stable on some institutionalised exchanges. This assessment can also be supported by the growing values of on-chain and off-chain transactions per day for major crypto-assets. On the other hand, price dispersion of crypto-assets across trading platforms is substantial, driven to some extent by wash trading. Moreover, the lack of detailed information on crypto-asset transactions hinders analysis.

4.4 Statistical initiatives to improve information on crypto-assets

Statistical issues related to crypto-assets, also within the broader topic of fintech, have been followed by the central bank community, for example the Irving Fisher Committee (IFC) on Central Banking Statistics.[39] Specifically, the IFC has set up a working group on fintech data issues[40] whose objective is to analyse and make possible recommendations for central bank statistics. The aim of the IFC’s work is twofold. First, it is to take stock of existing data sources and assess central banks’ additional information needs, which should be addressed through the IFC survey of the member central banks. Second, it is to investigate key data gaps, together with the costs and benefits of initiatives to address them, and provide guidance for developing adequate statistical definitions.

Furthermore, the statistics community[41] has started to investigate the statistical classification of crypto-assets in the System of National Accounts (SNA), which may have significant implications on the measurement of GDP and other key indictors and provide further insight into crypto-asset-related activities. National accounts are a data source for various economic indicators, such as GDP and its components and derived indicators, which provide insight, for example, into the size of the economy and the main drivers of economic activity. The statistical classification of crypto-assets and related activity in the SNA may significantly impact key indicators, including the GDP for some countries, depending on the method chosen.[42] Complexity in the statistical classification of crypto-assets derives from the very characteristic of crypto-assets not representing a financial claim on, or a liability of, any identifiable entity. Developing harmonised statistical treatment of crypto-assets in line with the general national accounts guidance for income, value generation, asset creation and accumulation would provide further insight and help to address existing data and analytical challenges.

Within the European System of Central Banks (ESCB), the ECB has established an informal network on crypto-asset data to analyse options to enhance information on crypto-assets. Following on from the initial internal work at the ECB, an informal network of representatives from the ESCB was created to analyse the options for addressing identified crypto-asset data gaps. The work of the network focuses on the improvement of the existing data and indicators, investigation into new sources for analysis and closer collaboration on analytical work covering statistical issues. In the medium term, the network plans to reflect also on the issues related to the classification of crypto-assets in central bank statistics.

Statistical initiatives involving central banks can provide valuable contributions to closing the identified crypto-asset data gaps in the future. There has been no comprehensive global initiative for developing and compiling statistics on crypto-assets in a structured way before. In the future, central banks can provide input with respect to the new data sources for information on the interlinkages of crypto-assets. Drawing from the available tools, central banks could contribute to closing data gaps via initiatives towards increased availability and transparency of data, indicators and methodologies, best practices, as well as potential statistical compilations.

5 Conclusions

Crypto-assets are enabled by DLT and characterised by the lack of an underlying claim. In the light of the implications they might have for the stability and efficiency of the financial system and the economy, and also for the fulfilment of the Eurosystem’s functions, crypto-assets warrant continuous monitoring. To this end, the ECB has set up a dataset based on high-quality publicly available aggregated data complemented with other data from some commercial sources using API and big data technologies. However, important gaps and challenges remain: exposures of financial institutions to crypto-assets, interlinkages with the regulated financial sectors and payment transactions that include the use of layered protocols are all examples of domains with prominent data gaps.

The challenges in measuring the phenomenon of crypto-assets are diverse and relate both to on-chain and off-chain data. Specifically, it is hard to retrieve public data on segments of the crypto-asset market that remain off the radar of public authorities; some relatively illiquid trading platforms may be affected by wash trading; and there is no consistency in the methodology and conventions used by institutionalised exchanges and commercial data providers. Moreover, new and unexpected data needs may well arise with further advancements in crypto-assets and related innovation.

Statistical initiatives by the ECB and the central banking community are expected to provide a valuable input to efforts aimed at closing the data gaps associated with crypto-assets. Looking ahead, the ECB will continue to work on indicators and data by dealing with the complexity and growing challenges encountered in analysing on-chain and layered protocol transactions. Furthermore, investigation will continue regarding the new data sources for information on interlinkages of crypto-assets. With respect to the off-chain transactions, amid a multitude of methodological options, further work will focus on increasing the availability and transparency of the reported data and the methodologies used, harmonising and enriching the metadata and developing best practices for indicators on crypto-assets.

- In 2018 the ECB established the Internal Crypto-Assets Task Force (ICA-TF), with a mandate to deepen the analysis of crypto-assets. For a summary of the outcome of the ICA-TF’s analysis, see “Crypto-assets: Implications for financial stability, monetary policy, and payments and market infrastructures”, Occasional Paper Series, No 223, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, May 2019.

- In this article the term “asset” is used to refer to something of value to some market participants. It is not used in a legal or accounting sense.

- See “Crypto-assets: Implications for financial stability, monetary policy, and payments and market infrastructures”, ibid.

- See “Crypto-assets: Implications for financial stability, monetary policy, and payments and market infrastructures”, ibid.

- In its “Report with advice to the European Commission on crypto-assets” (January 2019), the European Banking Authority (EBA) states that, to qualify as e-money, assets must satisfy the definition of electronic money as set out in the second Electronic Money Directive (Section 2.1.1). In particular, the assets must represent a claim on the issuer (thereby excluding crypto-assets as defined in this article). In parallel, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) considers that assets like bitcoin are unlikely to qualify as financial instruments (see ESMA’s “Advice: Initial Coin Offerings and Crypto-Assets”, paragraph 80, January 2019).

- With the exception of anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) requirements under the fifth EU anti-money laundering directive, Directive (EU) 2018/843 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending Directive (EU) 2015/849 on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing, and amending Directives 2009/138/EC and 2013/36/EU (OJ L 156, 19.6.2018, p. 43).

- Following the EBA’s and ESMA’s advice (see footnote 5), the European Commission’s Vice-President Dombrovskis announced in his speech at the Eurofi High-level Seminar 2019 in Bucharest, Romania, that the Commission had initiated a feasibility study on a possible common regulatory approach at the EU level.

- See “Virtual Currencies – Key Definitions and Potential AML/CFT Risks”, Financial Action Task Force, June 2014. Subsequently, the Financial Action Task Force updated the International Standards to clarify their application to virtual assets and virtual asset service providers by amending Recommendation 15, “New Technologies”, and by adding two new definitions to the FATF Glossary.

- See “Report with advice for the European Commission on crypto-assets”, ibid.

- See “2nd Global Cryptoasset Benchmarking Study”, Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance, 2019.

- The “Global Cryptocurrency Benchmarking Study” by the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (2017) reported that 86% of participating payment companies were using bitcoin as their primary “payment rail” for cross-border transactions.

- See “2nd Global Cryptoasset Benchmarking Study”, ibid.

- For an assessment of these implications, see “Crypto-assets: Implications for financial stability, monetary policy, and payments and market infrastructures”, ibid. In fact, crypto-assets may have broader risk implications – for example, they may weaken financial system integrity and lend themselves to money laundering and the financing of terrorism – and raise consumer/investor protection concerns. These risks are not the primary focus of the ECB’s analysis.

- See “Statement on crypto-assets”, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 13 March 2019.

- See “Report with advice for the European Commission on crypto-assets”, ibid.

- In “Crypto-assets: Implications for financial stability, monetary policy, and payments and market infrastructures”, ibid, see Section 4.1 entitled “Potential implications for monetary policy”.

- In particular, crypto-assets are not on the list of central counterparties’ eligible collateral of the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2016/2251 of 4 October 2016 supplementing Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council on OTC derivatives, central counterparties and trade repositories with regard to regulatory technical standards for risk-mitigation techniques for OTC derivative contracts not cleared by a central counterparty (C/2016/6329) (OJ L 340, 15.12.2016, p. 9–46). Similarly, permitted central counterparties’ investments do not contemplate crypto-assets under Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2012 on OTC derivatives, central counterparties and trade repositories (OJ L 201, 27.7.2012, p. 1–59). In “Crypto-assets: Implications for financial stability, monetary policy, and payments and market infrastructures”, see Section 4.4 entitled “Risks to financial market infrastructures”.

- APIs enable users to access data providers’ databases by means of an automated set of queries provided via Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP – the protocol underlying internet websites) and return data.

- For example, the calculation of the market capitalisation required to cross-map and harmonise identifiers and naming conventions for crypto-assets as data from different providers needed to be integrated in order to use circulating supply as a preferred component for this indicator. Harmonisation of units also added an extra layer of complexity, as it required synthetic exchange rates to be calculated for all crypto-assets covered in the dataset.

- See Securities holdings statistics on the ECB’s website for more information.

- These indivisible units are sometimes called “unspent transaction outputs” (UTXOs).

- Understanding which part of the outputs of a transaction is the intended transfer and which constitutes change to the sender is not trivial. See Athey, S., Parashkevov, I., Sarukkai, V. and Xia, J., “Bitcoin Pricing, Adoption, and Usage: Theory and Evidence”, Working Paper, No 3469, Stanford Graduate School of Business, August 2016.

- See Pay-to-Endpoint and Coinjoin initiatives.

- The same approach could be used to record and transfer either traditional assets or crypto-assets.

- See Makarov, I. and Shoar, A., “Trading and Arbitrage in Cryptocurrency Markets”, May 2018.

- See Moore T. and Christin, N., “Beware the Middleman: Empirical Analysis of Bitcoin-Exchange Risk”, in: Sadeghi, A.R. (ed.) Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 7859, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013. The authors have found that transaction volume is positively correlated with a breach. At the same time, average transaction volume is negatively correlated with the probability that a trading platform will close prematurely.

- For example, for bitcoin futures traded at CME the contract units and settlement date are five bitcoin and mid-month, compared with one bitcoin and end-month in the case of CBOE.

- Contracts traded on the CME are settled based on the Bitcoin Reference Rate (BRR) index, which aggregates bitcoin trading activity across a representative sample of bitcoin exchanges between 15:00 and 16:00 GMT. Contracts traded on CBOE are settled based on the price obtained from the Gemini exchange at 16:00 GMT on the final settlement date.

- For more information on the ETPs traded, see SIX Swiss Exchange.

- See tracker certificates.

- For example, Amun ETPs follow the methodology of CryptoCompare’s Aggregate Pricing Index (CCCAGG). XBT Provider AB, issuer of crypto-asset trackers, follows pricing on specified platforms, i.e. OKCoin, Kraken, Bitstamp, Bitfinex, ItBit, Gemini and GDAX for bitcoin, and Poloniex, Kraken, Bitfinex, GDAX and Gemini for Ethereum, which also fulfil several selection criteria (e.g. markets are required (i) to publish, on a continuous and regular basis, bid-ask spreads and the last price in USD; (ii) not to be declared unlawful; (iii) to represent at least 5% of the total 30-day cumulative volume for all the platforms; and (iv) to settle fiat currency and transfers within seven and two local business days respectively).

- See, for example, Bloomberg Galaxy Crypto Index or CryptoCompare’s Aggregate Pricing Index (CCCAGG).

- See, for example, Bitwise Cryptoasset Index Methodology.

- See, for example, CCI30 Crypto Currency Index 30.

- For example, CRIX, Index for Cryptocurrencies, Simon Trimborn, Wolfgang Karl Härdle, Journal of Empirical Finance, Volume 49, December 2018, pp. 107-122.

- CRIX, Index for Cryptocurrencies, ibid.

- See, for example, https://www.sec.gov/comments/sr-nysearca-2019-01/srnysearca201901-5164833-183434.pdf.

- “What drives bitcoin adoption by retailers”, Working Paper, No 585, De Nederlandsche Bank, 2018.

- For more information see the BIS website.

- See “2018 IFC Annual report”, Irving Fisher Committee on Central Bank Statistics, Bank for International Settlements, March 2019.

- For example, within the Expert Group on National Accounts of the United Nations Statistical Commission.

- See, for example, “How to deal with Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies in the System of National Accounts?”, OECD, 2018 and “Treatment of Crypto Assets in Macroeconomic Statistics”, IMF, 2018.