Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 4/2022.

In this box, we present a new measure of domestic inflation for the euro area that takes into account the import intensity of HICP items. For this new indicator, the import intensities of HICP items are derived using information from national accounts and input-output tables. The HICP items with a relatively low import intensity are subsequently aggregated to what is referred to as a “Low IMport Intensity” (LIMI) inflation indicator.[3] The threshold for the import intensities, below which an HICP item is included in the indicator, is determined on the basis of empirical criteria. While the ECB’s inflation target is formulated in terms of headline inflation, the concept of domestic inflation is of analytical relevance to monetary policy, as it features prominently in the monetary policy transmission mechanism.[4] The GDP deflator is a commonly used indicator of domestic inflation, but while it discounts for imported inflation it captures price developments beyond consumer prices, such as prices for investment goods or exports that may not be very closely linked to domestically-driven consumer price inflation. In addition, standard exclusion-based indicators of core inflation may still include items that may have a high import intensity. The newly developed LIMI inflation indicator can complement some of these other indicators. It suggests that, although the sharp rise in headline inflation is mainly explained by imported inflation, domestic inflationary pressures have also increased over the past year.[5]

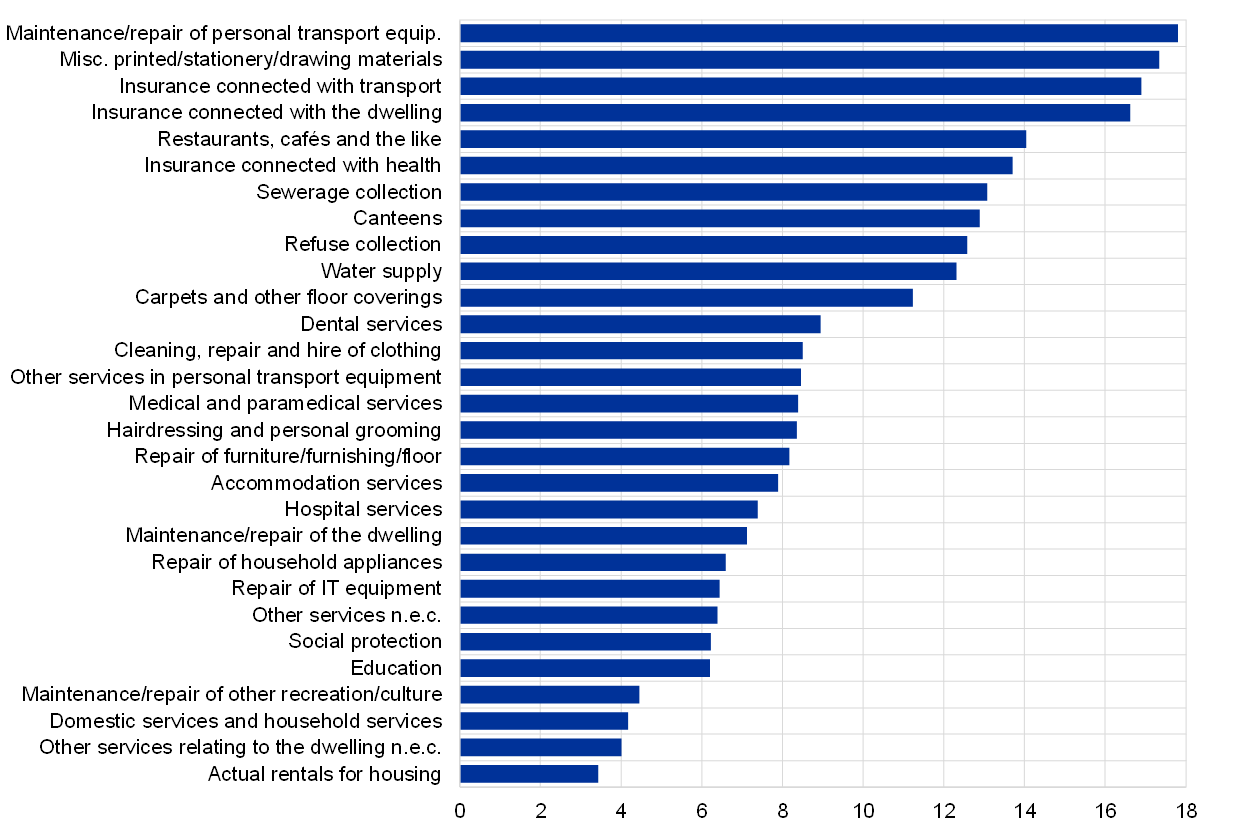

The import intensity of each HICP item is computed as the after-tax direct and indirect import content of private consumption. The higher the import content of a private consumption item, the more its price should react to international factors, given that the after-tax import content of consumption is approximately equal to the long-run elasticity of consumer price inflation to import price changes.[6] The total import content comprises the direct import content of private consumption (i.e. extra-euro area imports of goods that are directly consumed by households) and the indirect import content of private consumption (i.e. extra-euro area imports of intermediate goods that are used in the euro area production of final consumption goods).The total import content of an HICP item is derived first by using information from input-output tables to estimate the import content of consumption products classified by activity and then by mapping those products to the 94 HICP items.[7] According to this approach, in 2017, the import intensity ranged from 19% to 32% for HICP energy items, was close to 22% for HICP food items, ranged between 3% and 68% for HICP services items and between 11% and 44% for HICP non-energy industrial goods items (Chart A).[8]

Chart A

HICP items with an import intensity of less than 18% in 2017

Sources: Eurostat, authors’ calculations.

Note: Due to space constraints, the bars only show HICP items (at the 4-digit COICOP level) with an import intensity of less than 18%, which is the threshold determined on the basis of the empirical assessment.

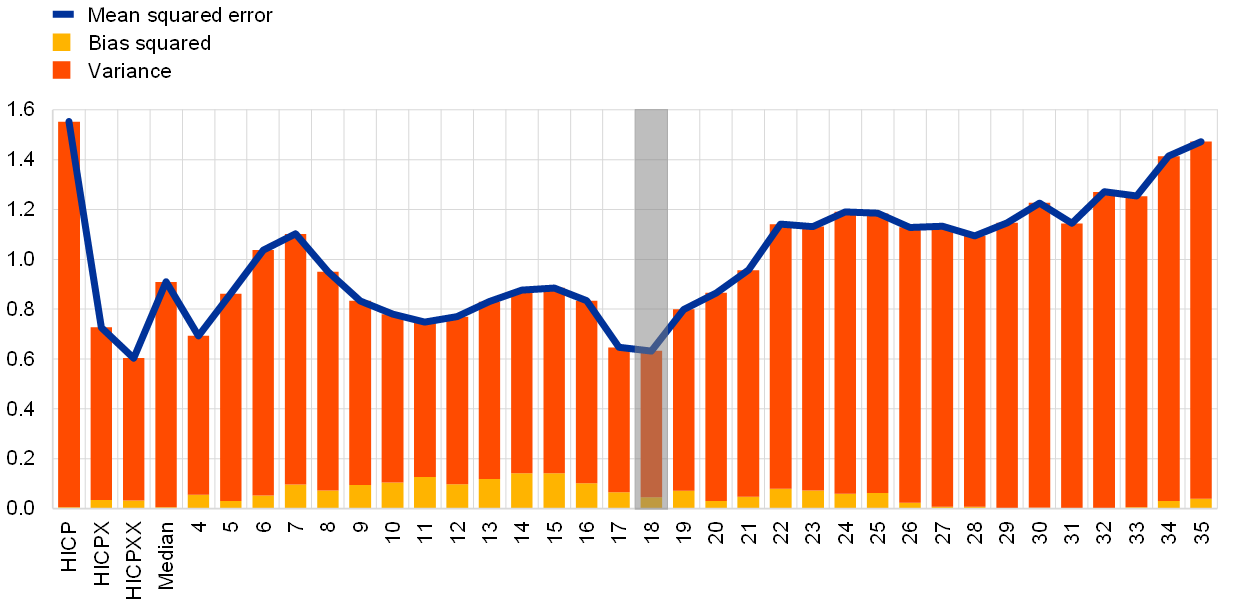

The ability to track headline inflation over the medium term is the main criterion used to determine an optimal threshold for the import intensity, with HICP items falling below that threshold being assigned to the LIMI inflation indicator. The threshold for our LIMI inflation indicator is determined according to empirical criteria. These include the historical bias and overall precision, as measured by the mean squared error (MSE), in tracking developments in headline inflation over the medium term.[9] For the post-global financial crisis (GFC) period, the bias tends to be larger for low import intensity threshold values (Chart B).[10] This may reflect the fact that it is to a large extent services items that tend to have a low import intensity, but at the same time also a relatively high average inflation rate. As the threshold rises, the bias tends to decrease as more non-energy industrial good items – which tend to have, on average, lower inflation rates – are covered by the LIMI inflation indicator. The indicator, based on a threshold of 18%, appears to provide the highest predictive accuracy, as well as a relatively modest bias.[11] Among standard exclusion-based indicators of underlying inflation, HICP inflation excluding energy, food, travel-related items and clothing and footwear (HICPXX) has the lowest MSE and is broadly comparable to that of the LIMI inflation indicator with a set threshold of 18%.

Chart B

Accuracy of candidate LIMI inflation indicators and common indicators of underlying inflation during the post-global financial crisis/pre-pandemic period

(x-axis: maximum import intensity in percentages)

Sources: Eurostat, authors’ calculations.

Notes: The metrics, i.e. the bias, variance and mean squared error, are calculated for candidate LIMI inflation indicators with import intensity thresholds ranging from 4% to 35% over the period from September 2008 to December 2019, with the preferred 18% threshold being shaded. The benchmark is defined as the annualised HICP growth rate over the subsequent two years. HICPX refers to HICP inflation excluding energy and food, while HICPXX refers to HICPX inflation excluding travel-related items and clothing and footwear.

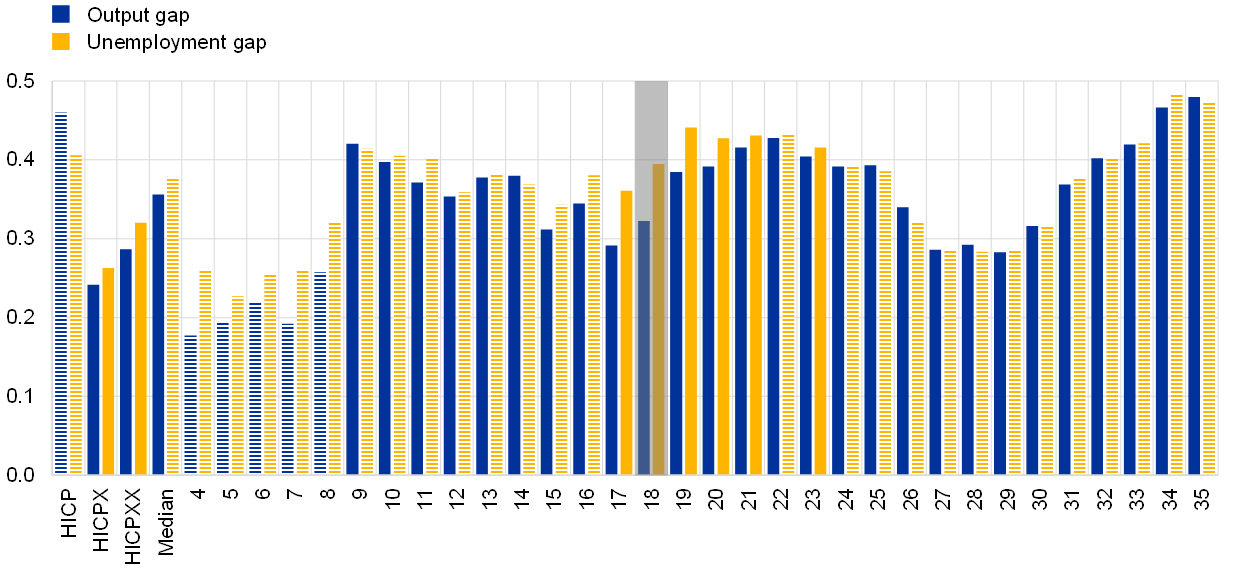

The LIMI inflation indicators generally show a strong link to business cycle conditions. The LIMI inflation indicator should, in principle, have a relatively high sensitivity to domestic slack. In a reduced-form Phillips curve regression based on the output gap, the short-run slope is highly significant in all regressions except in the cases of LIMI inflation indicators with import threshold values of 8% or lower.[12] The long-run slopes that are significant lie in the range from around 0.24 to 0.48. When using the unemployment gap as the measure of slack, the slopes are generally significant for an import threshold of between 17% and 23%. Taken together, a relatively low MSE points to a threshold of 18% for the LIMI inflation indicator. This choice is supported by a strongly significant Phillips curve slope for both the output gap and unemployment gap for this indicator.[13]

Chart C

Long-run slope in Phillips curve regression of LIMI inflation indicators and common indicators of underlying inflation

(x-axis: maximum import intensity in percentages)

Sources: Eurostat, authors’ calculations.

Notes: HICPX refers to HICP inflation excluding energy and food, while HICPXX refers to HICPX inflation excluding travel-related items and clothing and footwear. The median is weighted. The sign of the slope for the unemployment gap is inverted. Corresponding short-run slopes that are not significant at the 1% level are shown in a horizontal striped pattern. The sample period is the second quarter of 2003 to the fourth quarter of 2019.

The LIMI inflation indicator, based on an import intensity threshold of 18%, comprises predominantly items in HICP services. From a total of 94 items in the HICP at the 4-digit COICOP level of disaggregation, the LIMI inflation indicator contained 29 items in 2017, down from 34 in 2010, accounting for 35% and 40% of the total by weight, respectively. This decline may partly reflect some increased prevalence of global supply chains over that period. Since food and energy items typically have an import intensity that is higher than the threshold of 18%, they tend not to be included in the LIMI inflation indicator. Most non-energy industrial goods items are also excluded.[14] Services items are included, with some exceptions such as transport-related services, package holidays, postal services and cultural services. Given that this indicator comprises predominantly services items, it also tends to have a higher average level of inflation than that of the HICP inflation excluding energy and food.[15]

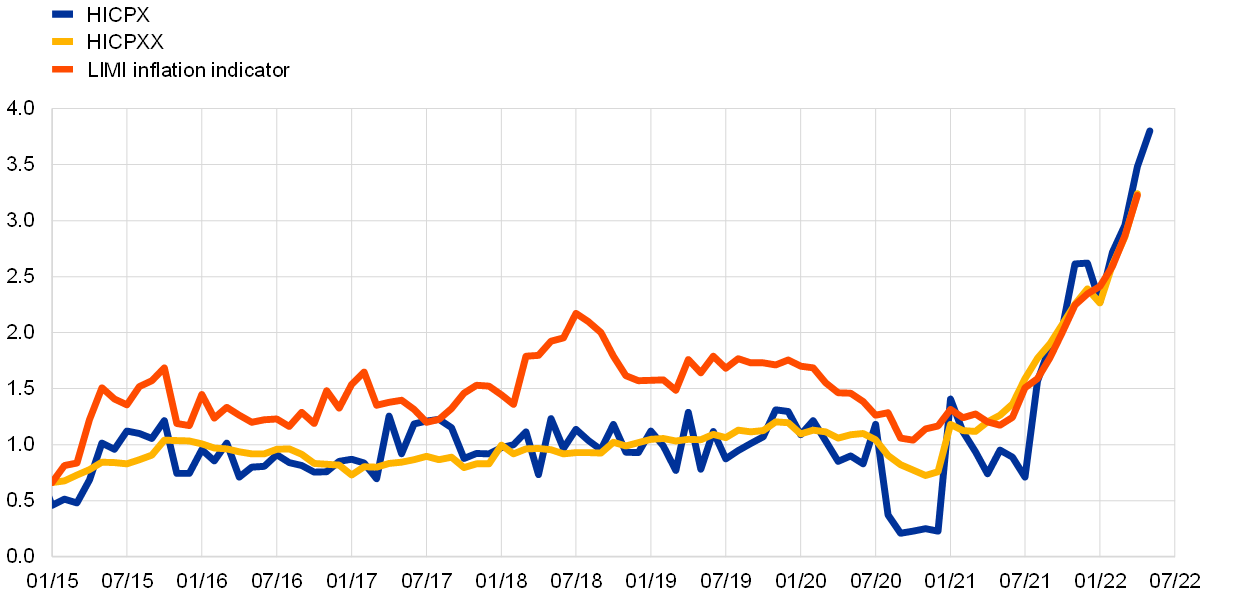

The LIMI inflation indicator suggests that, although the sharp rise in headline inflation is mainly explained by imported inflation, domestic inflationary pressures have also increased over the past year. The LIMI inflation indicator points to some increase in underlying inflationary pressures in the years immediately preceding the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic (Chart D). Subsequently, after a steep decline following the onset of the pandemic, the LIMI inflation indicator started on an upward trajectory in mid-2021.[16] This signal is broadly corroborated by the HICPXX. The LIMI inflation indicator, as well as the HICPXX, has been less affected than the HICPX by the strong volatility in travel-related services during the pandemic, as some of these items have an import content higher than the threshold of 18%. The LIMI inflation indicator also suggests that recent high levels of inflation are mainly imported, reflecting global shocks to supply and demand that are increasingly spilling over to the euro area economy through import prices (Chart E).

Chart D

LIMI inflation indicator in comparison with common indicators of underlying inflation

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat, authors’ calculations.

Notes: The LIMI inflation indicator is based on an import content threshold of 18%. HICPX refers to HICP inflation excluding energy and food, while HICPXX refers to HICPX inflation excluding travel-related items and clothing and footwear. The latest observations are for May 2022 for the HICPX (flash estimate) and April 2022 for the remaining HICP items.

Chart E

Decomposition of HICP inflation

(annual percentage changes; percentage points)

Sources: Eurostat, authors’ calculations.

Notes: The items with a lower import content correlate with those in the indicator of domestic inflation based on an import content threshold of 18%. The latest observations are for May 2022 for the HICP (flash estimate) and April 2022 for the remaining HICP items.

The LIMI inflation indicator can provide supplementary information for an assessment of underlying inflationary pressures. Particularly at times of large swings in international commodity prices or movements in euro exchange rates, this domestic inflation indicator can help to gauge the persistence of underlying inflation developments.[17] Still, as is the case with other indicators of underlying inflation, the accuracy of the LIMI inflation indicator can be episodic.[18] Also, since import intensities can change over time, the composition of the HICP items in the domestic inflation indicator can also shift.[19] Generally, it would be helpful to have more detailed information available about the import intensity of HICP components at a higher level of disaggregation. Overall, the LIMI inflation indicator should be used as a supplementary indicator within a broader set of indicators of underlying inflation. Furthermore, an assessment based on these indicators should be complemented by a more structural analysis of the driving forces to better understand the inflation process.

Deutsche Bundesbank.

Deutsche Bundesbank.

In general, HICPs are designed according to the domestic concept, i.e. the HICP refers to products that are bought in a given country. By contrast, the idea behind the indicator of “domestic” inflation means that some parts of HICP components are produced in a foreign country, such that price developments in those “non-domestic” parts should mainly be driven by foreign market conditions.

The concept of domestic inflation, as used in this box, is closely related to the concept of non-tradable inflation. The difference is that the concept of non-tradable inflation considers the export intensity and the import intensity of different goods and services for all uses, while domestic inflation refers to goods and services produced for domestic consumption with a low import intensity.

See F. Panetta, “Small steps in a dark room: guiding policy on the path out of the pandemic”, speech at the European University Institute, 28 February 2022, and F. Panetta “Patient monetary policy amid a rocky recovery”, speech at Sciences Po, 24 November 2021. Note that the LIMI inflation indicator referred to in these speeches is based on the World Input-Output Database (WIOD), which was subsequently revised using a mapping system based on Eurostat’s FIGARO (Full International and Global Accounts for Research in Input-Output analysis) database.

One caveat here is that the degree of substitutability with imports could also affect prices and this is not taken fully into account. For example, even for an item with zero import intensity, domestic firms may keep the price equal to the international price to avoid losing market share to imported alternatives. Furthermore, going beyond our largely statistical approach, domestic inflation could also be defined according to the sources of the economic shocks. For example, if the price of a good – even with a high import intensity – were to be strongly influenced by euro area demand, then this imported inflation could still be described as “domestic” in the sense that it may come under the control of domestic monetary policy.

The main data sources used to derive the import intensity for individual HICP items are the FIGARO database, as well as the corresponding supply and use tables. FIGARO data are provided at an annual frequency and for sufficient sectors; they cover the period 2010 to 2017 (the calculations for 2000-09 are instead based on WIOD data). The computation of the correspondence tables between the 64 final Classification of Products by Activity (CPA) in the FIGARO database and the 94 HICP items at the 4-digit COICOP level is based on a Eurostat correspondence list (COICOP stands for the classification of individual consumption by purpose). In addition, Eurostat data on wholesale and retail trade, final consumption expenditure at purchaser’s prices, as well as the COICOP weights of the individual HICP items, are used as auxiliary data to conduct the mapping. The import intensities change each year from 2000 to 2017 and are fixed at 2017 values thereafter until the next release of FIGARO data. The mapping is based on publicly available information and it is only an approximation of the import intensity.

The two HICP services items entitled passenger transport by air and passenger transport by the sea and inland water way show very high import intensities. The reason is that it is not possible to compute the import intensity for transport services of passengers and goods separately, as the corresponding CPA items, water and air transport, do not discriminate between the two. The item with the third highest import intensity is package holidays, at 35%.

An estimate of the persistent component of inflation, which is unobservable, is needed to serve as a benchmark. The main benchmark in month t is defined as the annualised HICP growth rate over the subsequent two years, i.e. 1,200*(pt+h– pt)/h where pt is the price level at time t and h is 24 months. The results are robust to the use of alternative proxies for the persistent component of inflation, such as a corresponding benchmark based on inflation three years ahead. The post-GFC sample period runs from September 2008 to December 2017. Data from January 2018 to December 2019 are needed to calculate the two-year ahead benchmark. Data from the pandemic period are not used.

Over the pre-GFC sample period, there is no clear optimum threshold for the import intensity. Much of the strong positive bias in the headline HICP during the pre-GFC sample period is accounted for by high average inflation rates for very oil-intensive items such as liquid fuels. These items have a high import intensity and tend to be excluded from the range of thresholds considered.

The pre-GFC period was characterised by persistently high commodity price inflation. If a commodity super-cycle were to reoccur, then LIMI inflation indicators with a low import intensity threshold that excludes many energy and food items would again likely show a large bias. For this reason, the LIMI inflation indicator with a threshold of 18% should only be used as a complementary indicator in a broader assessment of developments in underlying inflation.

The Phillips curve specification is as follows: yi(t) = α + ρ * yi(t-1) + βi * slack (t-1) + ε(t) where yi(t) is the annualised seasonally-adjusted quarter-on-quarter growth rate of the indicator of domestic inflation i (associated with a given import intensity threshold) at time t and the slack is either the output gap or the unemployment gap.

In addition, over the post-GFC to pre-pandemic period, the only LIMI inflation indicator that shows a significant slope for the unemployment gap is the one with the 18% threshold.

The following non-energy industrial goods items are included from 2017 onwards: carpets and other floor coverings; water supply; and miscellaneous printed matter, stationery and drawing materials.

See the box entitled “What is behind the change in the gap between services price inflation and goods price inflation?”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 5, ECB, 2019.

This upward trajectory could be partly accounted for by the indirect effects of higher international commodity prices on the HICP items in the LIMI inflation indicator. However, the magnitude of these effects is difficult to quantify.

This is assuming that such commodity price and exchange rate movements have one-off level effects.

See Chapter 6 in “Inflation measurement and its assessment in the ECB’s monetary policy strategy review”, Work stream on inflation measurement, ECB Occasional Paper Series, No 265, September 2021.

While these changes in composition tend to be infrequent, this could potentially be a factor that influences the trajectory of the LIMI inflation indicator and this will need to be monitored.