Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 4/2024.

The ECB’s labour hoarding indicator measures the share of firms that have not reduced their workforce despite a worsening of their firm-specific outlook. This indicator is constructed for the first time using the ECB and European Commission Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE) in the euro area. The labour hoarding indicator can be decomposed into two margins: an “activity margin”, which captures the share of firms that have faced a deterioration in their specific outlook, and an “employment margin”, indicating the share of firms that have not reduced their workforce despite reporting a deterioration in their outlook. The activity margin depicts to what extent adverse shocks affect the outlook of firms in the euro area, while the employment margin reflects firms’ ability to hold on to their workforce while facing an adverse shock.[1]

In the first quarter of 2024, the share of firms hoarding labour remained above pre-pandemic levels (Chart A).[2] The labour hoarding indicator stood at 22.2% in the first quarter of 2024, at relatively high levels compared with the pre-pandemic average of 12.7% (for the period from the third quarter of 2014 to the third quarter of 2019). This indicator reveals that a significant share of firms (30.2%) have been facing a worsening of their own economic outlook over the previous six months. Of these firms, 73.5% avoided reducing their workforce during that period. The ability of firms to retain workers decreased slightly in the first quarter of 2024, from 76.1% in the third quarter of 2023, but it remains around the average level recorded before the pandemic. Hence, the activity margin grew considerably with respect to the pre-pandemic period, while the employment margin remained broadly unchanged.

Chart A

Labour hoarding indicator

(share of firms, percentages)

Sources: ECB and European Commission Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE).

Notes: The labour hoarding indicator is the share of firms that have not reduced their workforce while facing a worsening of their firm-specific outlook. The activity margin captures the share of firms that have faced a deterioration in their specific outlook over the previous six-month period, while the employment margin refers to the share of firms that have not reduced their workforce of all those that reported a deterioration in their outlook over the same period. First quarter waves cover October-March; third quarter waves cover April-September.

The labour hoarding indicator has broadly increased from levels seen prior to the onset of the pandemic, most prominently for manufacturing (Chart B). In the first quarter of 2024, the labour hoarding indicator stood at 22.8% for manufacturing, 19.6% for construction and 22.4% for market services. Labour hoarding remained considerably high in all sectors compared with the period before the pandemic, when these three sectors had average levels of 11.2%, 11.4% and 13.3% respectively. More recently, following the surge in energy prices, the increase in labour hoarding was most salient in the manufacturing sector, where it peaked at 35.6% in the third quarter of 2022. Firms in other sectors also undertook labour hoarding in response to deteriorating business conditions, with 25.6% of firms in construction and 26.5% of firms in market services reporting not reducing their workforce following a worsening in their own economic outlook.

Chart B

Labour hoarding indicator across sectors

(share of firms, percentages)

Sources: ECB and European Commission Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE).

Notes: The sectoral labour hoarding indicator is the share of firms that have not reduced their workforce while facing a worsening of their firm-specific outlook among all the firms in a given sector of economic activity.

The profit margins of firms increased substantially with the recovery after the pandemic and, in 2022, were at their highest levels in a decade (Chart C).[3] Firms’ profit margins (before taxes) rose from an average of 4.3% of operating revenues in the period 2014-19 to around 5.8% in 2022. At the firm level, a similar increase was observed for the average and median firms. For the average firm, profit margins rose from 3.8% in 2014-19 to 5.3% in 2022, while for the median firm they went from 2.8% in 2014-19 to 3.9% in 2022.

Chart C

Firms’ profit margins over time

(percentages)

Sources: ECB and European Commission Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE), and Moody’s ORBIS.

Notes: The SAFE-ORBIS aggregate profit margin is calculated by summing the profits before taxes and revenues of all the firms in each ORBIS balance sheet year before calculating the profit margin ratio. There is a time lag before the balance sheet records become available in ORBIS; the latest available year for the profit margins in our analysis is 2022.

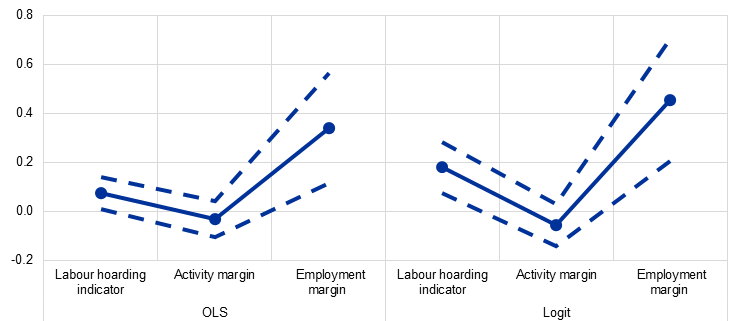

Higher profit margins are estimated to have improved the ability of firms to hoard labour in the event of an adverse shock to their economic outlook (Chart D). Firm-level regressions are performed to estimate the relationship between profit margins and labour hoarding.[4] A 1 percentage point increase in the profit margin of a firm is estimated to add around 0.2 percentage points to the share of firms hoarding labour in response to a worsening outlook. The rise in labour hoarding is driven by the employment margin, which is estimated to expand by roughly 0.4 percentage points, while the activity margin is estimated to remain broadly unaffected by the higher profit margin.[5] This implies that the growth in profit margins helped firms avoid having to reduce their workforce after being hit by shocks that worsened their economic outlook following the pandemic.

Chart D

Labour hoarding impact from a 1 percentage point increase in a firm’s profit margin

(percentage points)

Sources: ECB and European Commission Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE), and Moody’s ORBIS.

Notes: The impact of a change in a firm’s profit margin is estimated using panel data methods by regressing the firm’s labour hoarding indicator on: (i) the firm’s profit margin for the preceding accounting year, (ii) a time effect to cater for changes in the business cycle, and (iii) firm-specific fixed effects. The ordinary least-squares (OLS) model has time-varying firm weights. The logit model has fixed firm-level weights.

The impact of higher profit margins on labour hoarding was broadly based across sectors but strongest for construction. The estimated impact of a higher profit margin on the labour hoarding indicator stands at 0.1 percentage points for the industrial sector, 0.5 percentage points for construction and 0.2 percentage points for market services. While overall shifts in labour hoarding were mostly driven in all sectors by external shocks that worsened the economic outlook of firms, the observed high profit margins remained an important factor in helping firms keep their ability to hoard labour elevated.

A tightening of profit margins may have implications for employment growth in the period ahead.[6] The high profit margins of 2021-22 are starting to normalise towards their pre-pandemic levels. Thus, declining profit margins are likely to be one possible factor reducing the scope for firms to undertake labour hoarding. Looking ahead, they are expected to provide less support to employment growth than previously.

The firm-specific outlook is assessed in response to the question “For each of the following factors, would you say that [your enterprise’s experiences and views] have improved, remained unchanged or deteriorated over the past six months?” and on the basis of the factor “Your enterprise-specific outlook with respect to your sales and profitability or business plan”. The question is qualitative. As such, it might imply that the firm’s outlook has remained favourable.

Complementing the increase in labour hoarding, employment developments have been supported by a decline in real wages. This factor is discussed in more detail in the box entitled “Drivers of employment growth in the euro area after the pandemic: a model-based perspective” in this issue of the Economic Bulletin.

We complement the information obtained from the SAFE with balance sheet information for firms for the preceding year, taken from ORBIS. Profit margins are defined as the ratio of a firm’s profits before taxes to its operating revenues. The growth in profit margins for 2021-22 in the SAFE-ORBIS dataset is consistent, although not directly comparable, with the increase in unit profits recorded at the macro level. There is a time lag before the balance sheet records become available in ORBIS, with the latest available year for SAFE-ORBIS profit margins in our analysis being 2022.

These regressions include firm-level fixed effects to account for a firm’s unobservable characteristics, as well as time-fixed effects that cater for changes in the business cycle and for the shifting composition of firms in each SAFE wave.

It should be emphasised that the decision of firms to undertake labour hoarding is rational and coherent with long-term profit maximisation goals. Profit-maximising firms choose to undertake labour hoarding when the costs of redundancies, re-employment and training exceed the costs of employee retention.

The recent developments in labour hoarding have also had an impact on labour productivity, as discussed in Arce, O. and Sondermann, D., “Low for long? Reasons for the recent decline in productivity”, The ECB Blog, 6 May 2024.