Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 2/2025.

This box analyses recent developments in the euro area rental market using data from the ECB Consumer Expectations Survey (CES). Rents are a large component of household spending, but their analysis has been somewhat challenging as harmonised data on households’ rent expenditure are not readily available across the euro area. The CES can contribute to filling this data gap as it collects timely information about household spending.[1] It also allows for the analysis of heterogeneity across the countries covered by the CES, as well as individual households.[2]

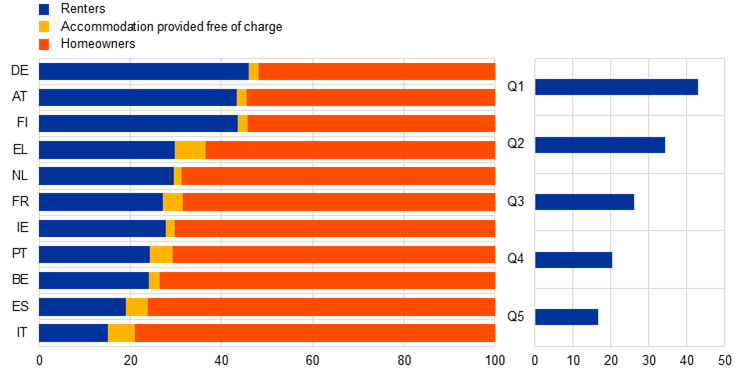

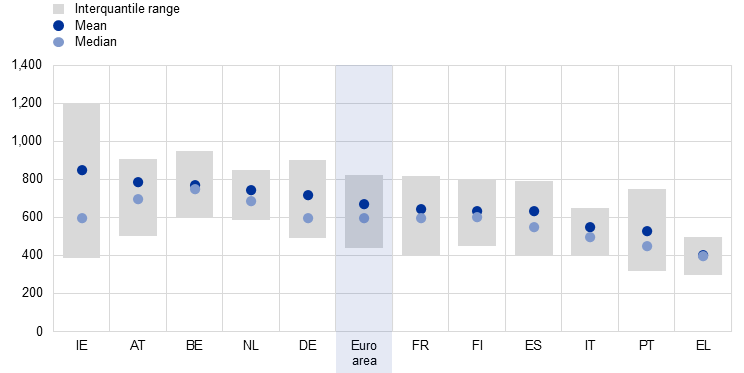

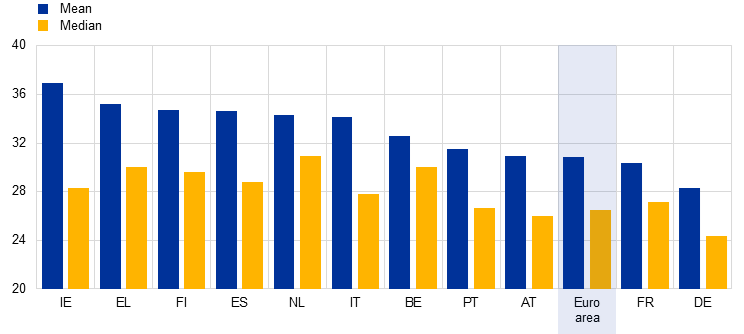

The share of renter households and the level of nominal rents vary considerably across countries. In the euro area, the average share of renters stands at around 28% and nominal rental expenditure amounts to around one-third of households’ monthly income. However, the share of renters varies widely across countries, currently ranging from 15% in Italy to almost 50% in Germany and Austria (Chart A, panel a, left-hand side).[3] The share of renters is highest in the lowest income group (Chart A, panel a, right-hand side). A closer look at the level of nominal rents also reveals a great deal of cross-country and within-country dispersion (Chart A, panel b).[4] Rent dispersion is very high in Ireland, where there are large location-dependent differences (i.e. between urban and rural areas; as also visible in the stark difference between the mean and the median), while it is much lower in Greece and the Netherlands. Overall, the highest nominal rents are observed in Ireland, Austria and Belgium. When looking at rent expenditure relative to household income (Chart A, panel c), the country ranking changes: Ireland still has the highest average rent to income ratio, followed by Greece and Finland, while Germany has the lowest. Countries where renters make up a larger share of the population also tend to have more high-income households as renters, which pushes down the average rent to income ratio.

Chart A

Share of renters and rent levels by country

a) Share of renters by country and income quintile

(percentages of respondents)

b) Rent levels and dispersion

(EUR per month)

c) Rent levels relative to monthly household income

(percentages of income)

Sources: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) and ECB calculations.

Notes: The calculations are based on weighted estimates. Panel a) comprises a full sample of respondents for 2024 and January 2025. Percentages of housing types are by country and income quintile (Q). Income quintiles are calculated for a full sample of respondents for all waves in 2024 and January 2025. Panel b) comprises a full sample of renters for January 2025 and panel c) comprises a full sample of renters from January 2024 to January 2025. The analysis of the rents does not control for dwelling size. Values are winsorised at the country level (at the second and 98th percentiles).

The CES-based rent expenditure growth indicator suggests that rent growth eased after peaking in the third quarter of 2023 but remained above 3% in the third quarter of 2024. The indicator is constructed as the weighted average of the individual household growth rates, once the data have been cleaned to ensure that they are not influenced by strong outliers or by composition effects from respondents entering or leaving the panel.[5] The average year-on-year rent growth rate in the euro area increased from the beginning of 2022, reaching a peak of above 5% in 2023 (Chart B, panel a) and declined gradually afterwards, remaining close to 3% for most of 2024. The CES-based rent indicator uses a more harmonised approach than the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP), which follows rental changes over time for the same households, regardless of whether they remain in the same dwelling or move. The resulting indicator is more responsive to inflation and the business cycle than HICP rents, especially for certain countries (e.g. Germany). This may be related to different practices, as the HICP regulation allows countries to choose which methodology they apply as reflected in the HICP methodological manual.[6]

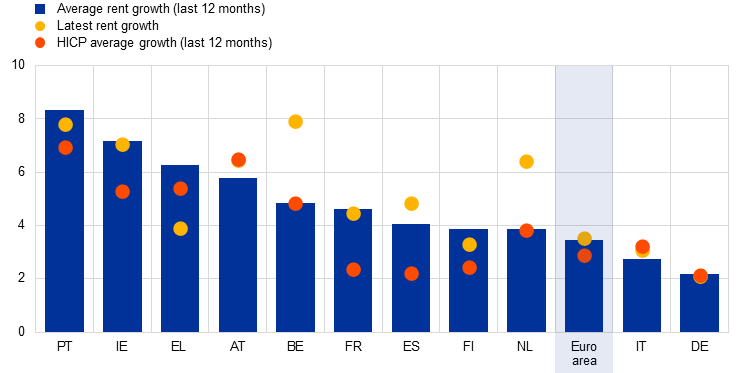

There have been substantial cross-country differences in reported rent growth. The average year-on-year rent growth reported in the CES over the last 12 months has been above 7% in Ireland and Portugal, but below 3% in the Netherlands, Germany and Italy (Chart B, panel b). In the third quarter of 2024 (the most recent values), households in Portugal reported the highest rent growth (this was also much higher than past averages), while the values for Italy and Finland were lower than their past averages. In Ireland and Austria, rent growth has remained consistently high.

Chart B

Rent growth in the euro area and by country

a) Rent growth in the euro area

(year-on-year percentage changes)

b) Rent growth by country

(year-on-year percentage changes)

Sources: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel b) comprises a full sample of renters. Calculations are based on weighted estimates. The latest two-quarter moving average for the year-on-year growth rate (yellow dots) refers to January 2025. The blue columns show the average rent growth for the sample period (January 2024 to January 2025). The red dots refer to average HICP rent growth over the past 12 months.

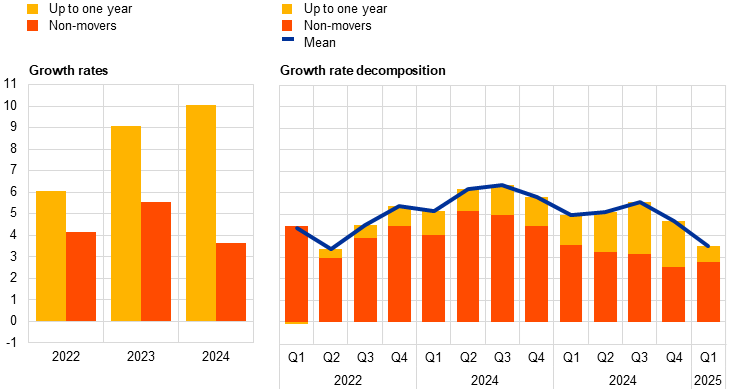

Recent CES-based rent growth per square metre has been more than proportionally driven by new rental contracts. The average rate of rent growth per square metre for households that have moved in the previous year has been consistently higher than the rent growth for households that have not moved; and it has increased steadily over the past three years (Chart C, panel a, left-hand side). General rent increases in the economy usually start with higher rents for new leases, as tenant protections on existing contracts encourage landlords to raise rents when there is a change of tenant. Over time, rents for existing contracts gradually rise as well. The higher rent growth for new contracts may have also been partly driven by households moving to higher-quality accommodation or to better areas. Indeed, the predominant reason indicated by households for changing accommodation was the desire to improve their living conditions. Decomposing the overall rent growth rate into contributions from recent movers (i.e. renters who have moved up to one year earlier) and non-movers shows that the latter play a bigger role in the overall growth rate as they account for a larger share. Nevertheless, given the higher rent growth in this segment, movers – who represent about 15% of renters – make a more than proportional contribution, accounting for around one-third of the overall growth rate (Chart C, panel a, right-hand side).

Chart C

Breakdown of rent growth

a) Rent growth per square metre – contributions by duration of residence

(year-on-year percentage changes, percentage change contributions)

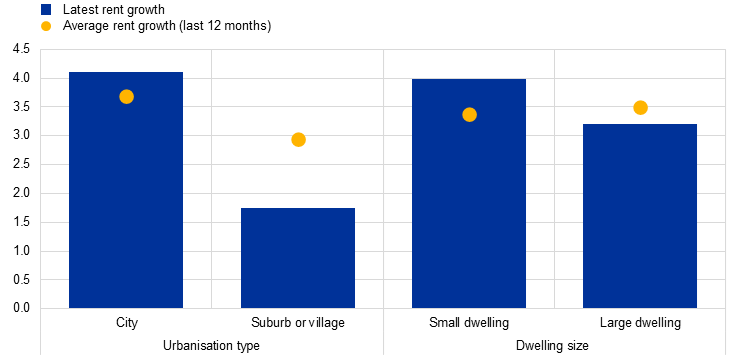

b) Rent growth by urbanisation type and dwelling size

(year-on-year percentage changes)

Sources: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Calculations are based on weighted estimates. Panel a) comprises a subsample of renters with a known duration of residence. The blue line depicts the combined two-quarter moving average of the year-on-year growth rate of the rents divided by square metres. “Up to one year” refers to the contribution of respondents who have lived in their current residence for one year or less. Panel b) comprises a full sample of renters. The latest two-quarter moving average of the year-on-year growth rate refers to January 2025. “Average rent growth” is the average of the year-on-year growth rates in the sample period (January 2024 to January 2025).

Recent rent growth reported in the CES has been higher in cities and for smaller dwellings. Chart C, panel b) shows that rent growth in cities has remained higher than rent growth in suburbs and rural areas and that the difference seems to have widened in the recent past. CES data also point to somewhat higher rent growth for smaller dwellings compared with larger ones, whereas growth rates were broadly equal in the past.

The CES-based rent tracker allows for timely in-depth monitoring of the rental market. These individual-level CES data can expand the possibilities of monitoring rental developments also with respect to heterogeneity across households. Future work will seek to further validate this indicator – including cross-validating the CES data with external sources. Furthermore, the role of quality adjustments in rent growth could be explored more thoroughly by considering factors such as dwelling age, location and renovation, to gauge the extent to which the growth rate reflects changes in housing quality.

Housing-related expenditure, including rent, house maintenance and insurance (excluding mortgage payments) is collected quarterly as part of a broader question on household consumption in 12 expenditure categories.

As of 2022 the countries covered by the CES are Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Netherlands, Austria, Portugal and Finland.

This is broadly in line with findings from EU statistics on income and living conditions and the Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Survey in terms of both country ranking and percentages.

The main rent growth indicator presented in this box does not account for systematic differences in quality and age across countries. However, these are controlled for in the non-mover series that considers only non-movers shown in Chart C, panel a), where growth rates are calculated for the rent of the same individuals in the same dwelling, 12 months apart.

The mean of individual growth rates is heavily trimmed to avoid the effects of outliers stemming from reporting errors. To do this, unrealistically large year-on-year changes (negative growth of less than 50% or positive growth of more than 200% within a year) are trimmed (removed from the sample). Additionally, rent increases and decreases of more than 50% are winsorised (observations exceeding the limits are replaced with the limit).To contain the impact of compositional changes, which could lead to mechanical effects unrelated to actual rental growth, a household’s rent only enters the growth indicator if the household is a renter both at the beginning and at the end of the 12-month period.

In the HICP, rentals can be calculated by following households, dwellings or landlords. This flexibility could potentially lead to different practices across national statistical offices that, in turn, could have a differential effect on the observed outcomes. For more details, see Section 12.4.4 of the HICP methodological guide.