Economic Bulletin Issue 1, 2021

Update on economic and monetary developments

Summary

The start of vaccination campaigns across the euro area is an important milestone in the resolution of the ongoing health crisis. Nonetheless, the pandemic continues to pose serious risks to public health and to the euro area and global economies. The renewed surge in coronavirus (COVID-19) infections and the restrictive and prolonged containment measures imposed in many euro area countries are disrupting economic activity. Activity in the manufacturing sector continues to hold up well, but services sector activity is being severely curbed, albeit to a lesser degree than during the first wave of the pandemic in early 2020. Output is likely to have contracted in the fourth quarter of 2020 and the intensification of the pandemic poses some downside risks to the short-term economic outlook. Inflation remains very low in the context of weak demand and significant slack in labour and product markets. Overall, the incoming data confirm the Governing Council’s previous baseline assessment of a pronounced near-term impact of the pandemic on the economy and a protracted weakness in inflation.

In this environment ample monetary stimulus remains essential to preserve favourable financing conditions over the pandemic period for all sectors of the economy. By helping to reduce uncertainty and bolster confidence, this will encourage consumer spending and business investment, underpinning economic activity and safeguarding medium-term price stability. Meanwhile, uncertainty remains high, including relating to the dynamics of the pandemic and the speed of vaccination campaigns. The Governing Council will continue to monitor developments in the exchange rate with regard to their possible implications for the medium-term inflation outlook. The Governing Council continues to stand ready to adjust all of its instruments, as appropriate, to ensure that inflation moves towards its aim in a sustained manner, in line with its commitment to symmetry.

The global economic recovery continued at the end of 2020, amid increasing headwinds from the resurgence of the pandemic. Economic activity in both the manufacturing and services sectors remains robust, although extended lockdowns in the countries more adversely affected by the pandemic increasingly pose downside risks. The recovery in global trade is ongoing, despite some signs of a loss in momentum towards the end of 2020. Global financial conditions remain highly accommodative, with equity markets being buoyed by COVID-19 vaccine-related developments, expansive fiscal policies and lower uncertainty regarding future trade relations between the European Union and the United Kingdom.

Over the review period (10 December 2020 to 20 January 2021) the forward curve of the euro overnight index average (EONIA) shifted upwards and flattened, which effectively removed most of its prior inversion. In general, risk sentiment improved and global market-based inflation expectations increased on the back of developments in the United States. Consequently, the euro area risk-free curve does not suggest firm market expectations of an imminent rate cut. At the same time, long-term sovereign bond yields in the euro area increased somewhat, but remained at very subdued levels overall. Risk assets performed well, with equity prices increasing on both sides of the Atlantic. US equities outperformed their euro area counterparts and reached new record highs. In foreign exchange markets, the euro depreciated slightly in trade-weighted terms.

Following the unprecedented fall in euro area output in the first half of 2020, economic growth rebounded strongly in the third quarter of the year. However, incoming economic data, surveys and high-frequency indicators suggest that the resurgence of the pandemic and the associated intensification of containment measures have likely led to a decline in activity in the fourth quarter of 2020 and are also expected to weigh on activity in the first quarter of this year. This profile is broadly in line with the baseline scenario of the December 2020 macroeconomic projections. Whereas services sector activity is being severely curtailed by the intensification of containment measures (albeit to a lesser extent than in the first wave of the pandemic in spring 2020), manufacturing activity is continuing to hold up well. While growth in the fourth quarter will be weak and very possibly negative, the relative resilience of the industrial sector suggests that there could be some upside risks to growth. Growth patterns in the euro area are expected to remain uneven, both across sectors and across countries. Looking ahead, the roll-out of vaccines, which started in late December, allows for greater confidence in the resolution of the health crisis. However, it will take time until widespread immunity is achieved, and further adverse developments related to the pandemic, with challenges for public health and economic prospects, cannot be ruled out. Over the medium term, the economic recovery in the euro area should be supported by favourable financing conditions, an expansionary fiscal stance and a recovery in demand as containment measures are lifted and uncertainty recedes.

Euro area annual HICP inflation remained unchanged for the fourth month in a row, standing at -0.3% in December. Headline inflation is expected to move into positive territory in early 2021 owing to the end of the temporary VAT reduction in Germany, upward base effects in energy price inflation and the impact of recent oil price increases. However, underlying price pressures will remain subdued owing to weak demand, notably in the tourism and travel-related sectors, as well as to low wage pressures and the appreciation of the euro exchange rate. Once the impact of the pandemic fades, a recovery in demand, supported by accommodative monetary and fiscal policies, will put upward pressure on inflation over the medium term. Survey-based measures and market-based indicators of longer-term inflation expectations remain at low levels, although market-based indicators of inflation expectations have increased slightly.

In November 2020, monetary dynamics in the euro area continued to reflect the impact of the coronavirus crisis. Broad money growth increased further, while growth in loans to the private sector remained stable, with moderate lending to non-financial corporations and resilient lending to households. Strong money growth continued to be supported by the ongoing asset purchases by the Eurosystem, which remain the largest source of money creation. The tightening of credit standards for loans to firms and to households continued in the fourth quarter of 2020 in the context of renewed COVID-19-related restrictions. Favourable lending rates have continued to support euro area economic growth.

Against this background, the Governing Council decided to reconfirm its very accommodative monetary policy stance.

First, the interest rate on the main refinancing operations and the interest rates on the marginal lending facility and the deposit facility will remain unchanged at 0.00%, 0.25% and -0.50% respectively. The Governing Council expects the key ECB interest rates to remain at their present or lower levels until it has seen the inflation outlook robustly converge to a level sufficiently close to, but below, 2% within its projection horizon, and such convergence has been consistently reflected in underlying inflation dynamics.

Second, the Governing Council will continue the purchases under the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) with a total envelope of €1,850 billion. The Governing Council will conduct net asset purchases under the PEPP until at least the end of March 2022 and, in any case, until it judges that the coronavirus crisis phase is over. The purchases under the PEPP will be conducted to preserve favourable financing conditions over the pandemic period. If favourable financing conditions can be maintained with asset purchase flows that do not exhaust the envelope over the net purchase horizon of the PEPP, the envelope need not be used in full. Equally, the envelope can be recalibrated if required to maintain favourable financing conditions to help counter the negative pandemic shock to the path of inflation.

The Governing Council will continue to reinvest the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the PEPP until at least the end of 2023. In any case, the future roll-off of the PEPP portfolio will be managed to avoid interference with the appropriate monetary policy stance.

Third, net purchases under the asset purchase programme (APP) will continue at a monthly pace of €20 billion. The Governing Council continues to expect monthly net asset purchases under the APP to run for as long as necessary to reinforce the accommodative impact of its policy rates, and to end shortly before it starts raising the key ECB interest rates.

The Governing Council also intends to continue reinvesting, in full, the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the APP for an extended period of time past the date when it starts raising the key ECB interest rates, and in any case for as long as necessary to maintain favourable liquidity conditions and an ample degree of monetary accommodation.

Finally, the Governing Council will continue to provide ample liquidity through its refinancing operations. In particular, the third series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III) remains an attractive source of funding for banks, supporting bank lending to firms and households.

The Governing Council continues to stand ready to adjust all of its instruments, as appropriate, to ensure that inflation moves towards its aim in a sustained manner, in line with its commitment to symmetry.

1 External environment

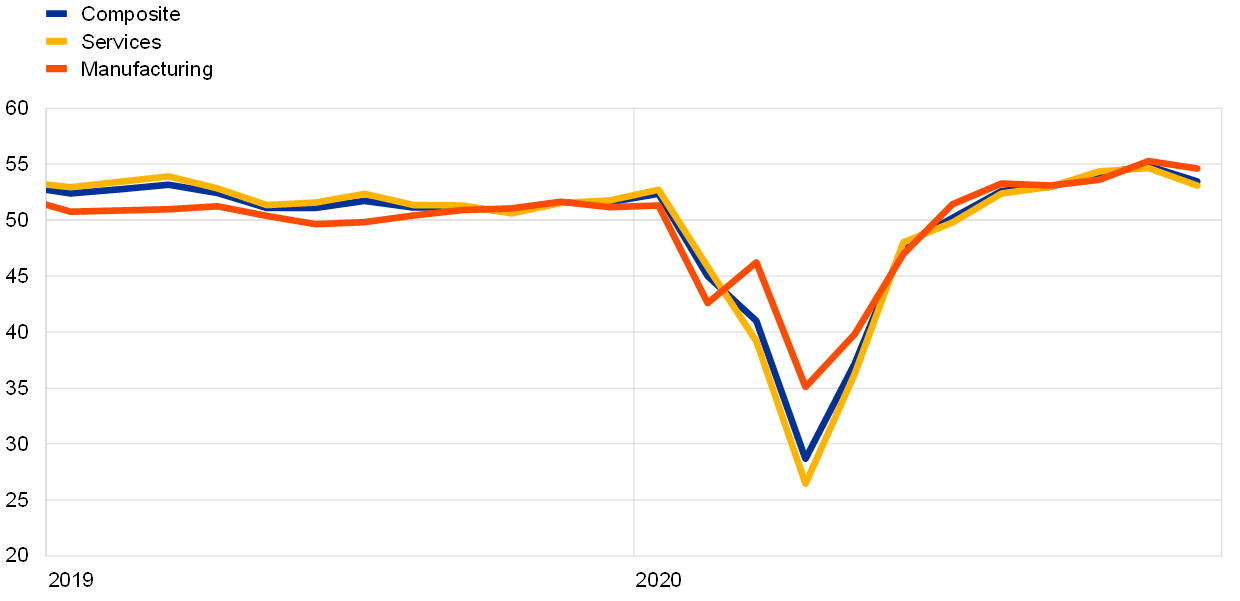

The recovery in global economic activity continued towards the end of 2020, albeit with rising headwinds from a re-intensification of the pandemic. Daily new cases of coronavirus (COVID-19) infections continued to rise globally. However, the most recent wave of the pandemic and the related containment measures have weighed less strongly on economic activity than the first wave in March and April 2020. This can be seen in the levels of the global manufacturing and services Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) excluding the euro area, which remained considerably higher at the end of 2020 compared with the sharp declines observed during the first wave (Chart 1). Looking ahead, global growth prospects this year will depend on how the pandemic evolves and the progress made on vaccination.

Chart 1

Global output PMI (excluding the euro area)

(diffusion indices)

Sources: Markit and ECB staff calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for December 2020.

Risks to the global outlook remain skewed to the downside, driven by a re-intensification of the COVID-19 pandemic. The global rise in daily new COVID-19 infections is creating headwinds to the global economic recovery. Countries that are strongly affected by COVID-19 have lost growth momentum. At the same time, there are upside risks relating to the decline in uncertainty regarding the trade relations between the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom, and the potential for a larger than expected fiscal support package in the United States given the new constellation of its Senate. However, slower than expected progress on vaccination rollout and further intensification of the pandemic could also imply stricter and longer lockdowns that will weigh on global growth prospects.

Global financial conditions remain highly accommodative in both advanced and emerging market economies. Equity markets edged higher, buoyed by COVID-19 vaccine-related developments, combined with supportive central bank action, expansive fiscal policies and lower uncertainty regarding future trade relations between the EU and the United Kingdom. In emerging market economies, equity prices have increased sharply, consistent with strong portfolio inflows into emerging market bond and equity funds, which have now offset the record outflows from those countries’ markets at the start of the COVID-19 crisis. Losses incurred by emerging market currencies in March 2020 also continued to be offset, although exchange rates remain substantially lower than pre-pandemic levels.

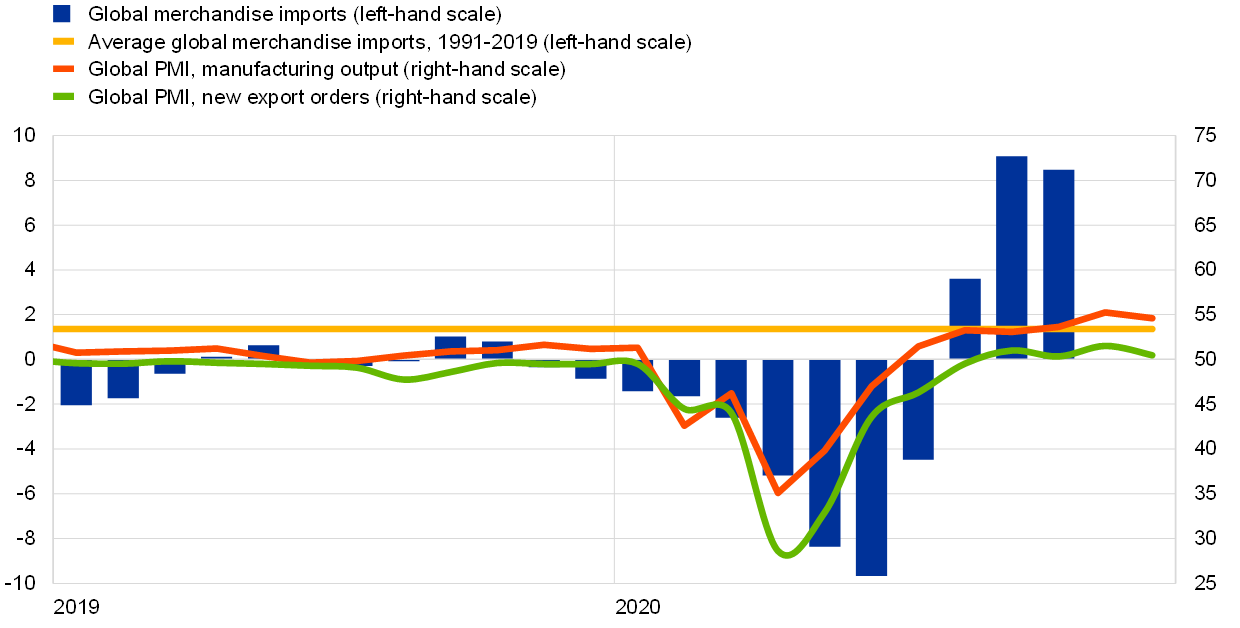

The recovery in global trade is ongoing, despite some signs of a loss in momentum. In the third quarter of 2020 data on goods trade pointed to a broad-based recovery across different categories. Intermediate goods, in particular, were a major driver of global exports in the third quarter, underlining the resilience of global value chains. At the same time, global PMI new export orders (excluding the euro area) fell in December, signalling some moderation in the momentum of global trade towards the end of 2020 (Chart 2).

Chart 2

Surveys and global trade in goods (excluding the euro area)

(left-hand scale: three-month-on-three-month percentage changes; right-hand scale: diffusion indices)

Sources: Markit, CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for October 2020 for global merchandise imports and December 2020 for PMIs.

Global inflation was stable in November. Annual consumer price inflation in the countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development remained at 1.2% in November, while inflation excluding energy and food remained at 1.6%. Looking ahead, global wage and price inflationary pressures are expected to remain contained amid ample spare capacity in most economies.

Commodity prices have continued to show broad-based increases since the last Governing Council meeting, with oil and non-energy prices increasing by more than 10%. The rebound in prices for most commodities over the past months is driven by a surge in global demand following the recovery from the COVID-19 shock. Demand from China for metals seems to be particularly strong. Copper prices have also been supported by government programmes for renewable infrastructure projects and electric vehicles, which are usually copper-intensive. Food prices have been supported by strong demand as governments stockpile and by supply disruptions as a result of hot and dry weather conditions in South America. In addition to rising demand, in early January oil prices also benefited from Saudi Arabia’s announcement of voluntary oil supply cuts of 1 million barrels per day.

Economic activity in the United States benefited from new fiscal stimulus amid headwinds from a weak labour market. Following a sharp recovery in the third quarter of 2020, economic growth is expected to slow in the fourth quarter. At the same time, a sizeable new fiscal stimulus package was agreed towards the end of last year, which will support consumption at a time when the labour market is still weak. Further stimulus measures are likely to be enacted by the new US administration. Meanwhile, the weakness in the labour market prevails, as suggested by rising permanent job losses through November, while the number of new job postings remains below pre-pandemic levels. The unemployment rate continued to be high at 6.7% in November, supported by a reduction in temporary layoffs. Overall, subdued consumer confidence, combined with rising numbers of daily new COVID-19 infections, pose downside risks to economic activity.

In Japan, the economic recovery stalled towards the end of 2020. While consumption remained relatively robust, growth in industrial production weakened in November, while the services PMI continues to stand below the neutral threshold, signalling ongoing weakness. While a new fiscal package of about 3.5% of GDP will support activity in the short term, a third wave of COVID-19 infections is prompting additional lockdown measures that will weigh on the growth outlook.

In the United Kingdom, notwithstanding support from the recent trade agreement with the EU, the near-term growth momentum remains weak. On 24 December 2020 the EU and the United Kingdom announced that they had reached an agreement on their future relationship, which ensures tariff-free goods trade and zero quotas on goods traded. However, companies face additional administrative burdens and longer border processes owing to customs and regulatory checks. This diminishes the uncertainty surrounding the Brexit negotiations, but the worsening pandemic situation and deteriorating labour market conditions continue to weigh on consumer confidence and demand. Official monthly UK GDP data and surveys signal a decline in growth into negative territory in the fourth quarter of 2020. In addition, pandemic developments escalated in December amid the emergence of a more infectious mutation of the virus. The government implemented a strict nationwide lockdown that will last at least through mid-February and further depress economic activity.

China, by contrast, experienced a continuation of its robust recovery. China’s GDP in the fourth quarter increased by 2.6% (quarter on quarter), which brings annual growth for 2020 to 2.3%. This makes China one of the few countries in the world to record positive economic growth in 2020. The GDP figures for the final quarter of 2020 indicate that the recovery momentum has broadened from investment towards consumption. PMI data also signal that the service sector is gaining strength as the pandemic remains broadly under control in China, notwithstanding lockdowns in several municipalities amid new cases.

2 Financial developments

The euro overnight index average (EONIA) and the new benchmark euro short-term rate (€STR) averaged -47 and -56 basis points respectively[1] over the review period (10 December 2020 to 20 January 2021). In the same period, excess liquidity increased by approximately €86 billion to around €3,537 billion, mainly reflecting asset purchases under the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) and the asset purchase programme (APP), which were partially offset by autonomous factors and voluntary repayments of TLTRO II operations. No TLTRO III operations were conducted during the review period.

At the same time, the EONIA forward curve shifted upwards and flattened, which effectively removed most of its prior inversion. Currently, the forward curve does not suggest firm market expectations of an imminent rate cut.[2] EONIA forward rates remain below zero for horizons up to 2028, reflecting continued market expectations of a prolonged period of negative interest rates.

Long-term sovereign bond yields in the euro area increased somewhat in the reference period but remained at very low levels overall, while long-term yields in other major jurisdictions increased more significantly. The GDP-weighted euro area ten-year sovereign bond yield increased by 5 basis points to -0.19% (see Chart 3), reacting little to the December meeting of the Governing Council, the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement that was announced on 24 December 2020 and pandemic-related news. Ten-year sovereign bond yields in the United Kingdom and the United States were more volatile, increasing by 10 and 17 basis points respectively. This mainly reflects a global “reflation” trend driven by increasing inflation expectations in the United States since early January.

Chart

Ten-year sovereign bond yields

3

(percentages per annum)

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Notes: Daily data. The vertical grey line denotes the start of the review period on 10 December 2020. The zoom window shows developments in sovereign yields since 1 April 2020. The latest observations are for 20 January 2021.

Euro area sovereign bond spreads relative to risk-free rates remained broadly unchanged. Some countries saw their sovereign bond yields increase in early January, broadly in parallel with risk-free rates. Specifically, ten-year German, French, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese sovereign spreads moved by 0, -3, -1, -2 and -2 basis points respectively to reach -0.27, -0.05, 0.84, 0.33 and 0.29 percentage points. The GDP-weighted euro area ten-year sovereign spread (relative to the corresponding risk-free rate) consequently decreased by 2 basis point to 0.06 percentage points and as such remained below its pre-pandemic level of February 2020.

Equity prices increased on both sides of the Atlantic, with equities in the United States outperforming those in the euro area and reaching new record highs. Equity prices in both the United States and Europe benefited from improved risk sentiment, driven in part by the global reflation trend which has been observed since early January. In the euro area, equity prices of non-financial corporations (NFCs) rose by 4.3% above the levels observed at the beginning of the review period. Bank equity prices also increased, albeit by a less pronounced 1.1%. In the United States, NFC equity prices increased by 5.5% – broadly in line with their euro area peers – while bank equity prices rose significantly, by 10.6%.

Euro area corporate bond spreads remained broadly stable and stand slightly above their pre-pandemic levels in some sectors. The spreads on both investment-grade NFC bonds and financial sector bonds relative to the risk-free rate remained stable over the review period to stand at 59 and 70 basis points respectively as at 20 January 2021. Overall, there have been only minor movements in corporate bond spreads since the December meeting of the Governing Council, with current conditions appearing highly predicated on ongoing fiscal and monetary policy support.

In foreign exchange markets, the euro depreciated slightly in trade-weighted terms (see Chart 4). Over the review period, the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro, as measured against the currencies of 42 of the euro area’s most important trading partners, depreciated by 0.7%. Regarding bilateral exchange rate developments, the euro depreciated against the pound sterling (by 2.8%), mainly reflecting the pound’s appreciation following the conclusion of the Brexit process with the announcement of the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement. Amid stabilisation in the global risk sentiment, the euro appreciated slightly against the Swiss franc (by 0.2%), while depreciating moderately against the Japanese yen (by 0.7%) and the US dollar (by 0.1%). The euro weakened against the Turkish lira (by 5.4%) and the Chinese renminbi (by 1.2%) and strengthened against the Brazilian real (by 4.5%).

Chart

Changes in the exchange rate of the euro vis-à-vis selected currencies

4

(percentage changes)

Source: ECB.

Notes: EER-42 is the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro against the currencies of 42 of the euro area’s most important trading partners. A positive (negative) change corresponds to an appreciation (depreciation) of the euro. All changes have been calculated using the foreign exchange rates prevailing on 20 January 2021.

3 Economic activity

Following the sharp and deep fall in euro area output in the first half of 2020, economic growth rebounded strongly in the third quarter, but it could well turn negative again in the fourth quarter. Total economic activity rose by 12.4% quarter on quarter in the third quarter of 2020, following declines of 11.7% and 3.7% in the second and first quarters respectively (Chart 5). A breakdown of growth in the third quarter shows that the recovery in output was broadly based, with increased domestic demand and net trade making positive contributions to growth totalling 11.4 and 2.3 percentage points respectively, while changes to inventories made a negative contribution totalling 1.2 percentage points. Hard data, survey results and high-frequency indicators all point to a renewed decline in GDP in the fourth quarter, which would be broadly in line with expectations, reflecting the intensification of containment measures as a result of the renewed rise in COVID-19 infection rates. Whereas service sector activity is being severely curtailed (albeit to a lesser extent than in the first wave in spring 2020), manufacturing activity is continuing to hold up well. Growth patterns in the euro area are expected to remain uneven across sectors, with the service sector being hardest hit by the pandemic (partly as a result of its sensitivity to social distancing measures). The same is true across countries, with developments in output being dependent on infection rates and efforts to contain the pandemic. Box 3 of this issue of the Economic Bulletin examines the drivers of regional differences in the economic impact of COVID-19 in the four largest euro area economies during the initial phase of the pandemic.

Chart 5

Euro area real GDP, the composite output Purchasing Managers’ Index and the Economic Sentiment Indicator

(left-hand scale: quarter-on-quarter percentage changes; right-hand scale: diffusion index)

Sources: Eurostat, European Commission, Markit and ECB calculations.

Notes: The two lines indicate monthly developments; the bars show quarterly data. The Economic Sentiment Indicator (ESI) has been standardised and rescaled so that it has the same mean and standard deviation as the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI). Dotted lines show quarterly averages of monthly PMI observations. The latest observations relate to the third quarter of 2020 for real GDP and December 2020 for the ESI and the PMI.

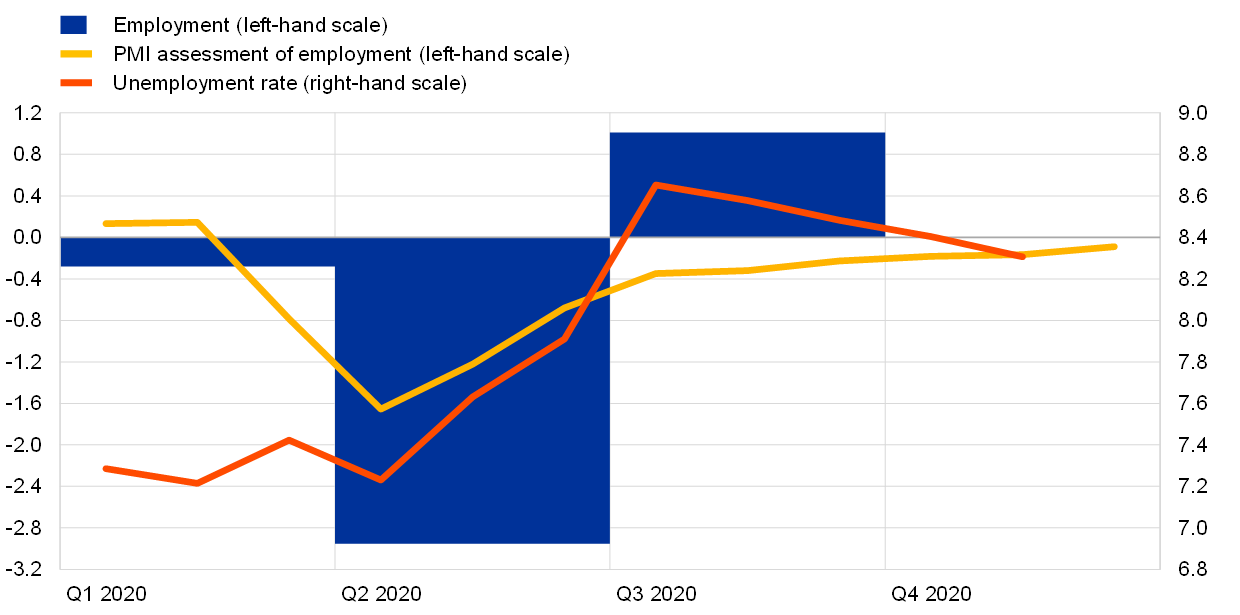

The unemployment rate in the euro area declined further in November 2020, helped by an increase in the number of workers covered by job retention schemes. The unemployment rate stood at 8.3% in November, down from 8.4% in October and just under 8.7% in July (Chart 6). At the same time, the figure for November was still around 1.1 percentage points higher than the rate seen in February prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Job retention schemes continued to cushion developments in the labour market, covering an estimated 5.8% of the labour force in November, up from around 5% in October in response to the latest lockdown measures.[3] Employment increased by 1.0% in the third quarter of 2020, following a decline of 3.0% in the second quarter. However, despite that improvement, employment was still 2.2% lower than it had been in the fourth quarter of 2019. Total hours worked increased by 14.8% in the third quarter, having declined by 13.6% in the second quarter, but remained 4.6% lower than they had been in the fourth quarter of 2019. Information on employment and hours worked in the fourth quarter of 2020 is not yet available.

Chart 6

Euro area employment, the PMI assessment of employment and the unemployment rate

(left-hand scale: quarter-on-quarter percentage changes, diffusion index; right-hand scale: percentages of the labour force)

Sources: Eurostat, Markit and ECB calculations.

Notes: The two lines indicate monthly developments; the bars show quarterly data. The PMI is expressed as a deviation from 50 divided by 10. The latest observations relate to the third quarter of 2020 for employment, December 2020 for the PMI and November 2020 for the unemployment rate.

Short-term labour market indicators have continued to improve somewhat, but are still signalling contractionary developments. The monthly PMI for employment rose marginally to stand at 49.1 in December – its eighth consecutive increase – up from 48.3 in November and 48.2 in October (Chart 6). The PMI for employment has recovered significantly since recording an all-time low in April 2020. However, it continues to point to a contraction in employment and could be read as an early indication of subdued employment prospects in the period ahead.

Having increased by some 14% in the third quarter, consumer spending weakened in the fourth quarter as social distancing measures were strengthened. In November, retail trade shrank by 6.1% month on month, following a 1.4% increase in October. At the same time, consumer confidence rebounded in December. The European Commission’s consumer confidence indicator rose to ‑13.9 in that month, up from -17.6 in November, mainly on account of relative improvements in the forward-looking components of the survey. However, consumer confidence remained low compared with pre-pandemic levels. While labour income has been severely affected by the COVID crisis, fiscal transfers have absorbed most of the impact on euro area households’ disposable income. The rebound in consumption in the third quarter of 2020 was reflected in a decline in the household saving rate, which fell to 17.3% in that quarter, down from 24.6% in the second quarter. Looking ahead, the saving rate is likely to remain above its pre‑COVID level in the short term on account of both precautionary and involuntary motives, before gradually normalising thereafter.[4]

After the strong growth seen in the third quarter, which was driven by very dynamic growth in machinery and equipment, corporate investment is likely to have increased slightly further in the fourth quarter, but the second wave of the pandemic suggests downside risks to investment in the first quarter of 2021. Industrial production of capital goods increased further in November, with its average value in October and November standing 6.6% higher than the level seen in the third quarter. Capacity utilisation increased to 76%, up from 72% in the third quarter, but was still 5 percentage points lower than it had been prior to the pandemic. Meanwhile, survey indicators for the capital goods sector (such as the European Commission’s industrial confidence indicator and the relevant PMI) tended to improve in the fourth quarter relative to the third quarter. In addition, the third quarter brought some relief to corporate balance sheets, with national accounts data indicating that gross operating surpluses rebounded by 12% in that quarter, following a cumulative decline of more than 14% in the first half of 2020. New loans to non‑financial corporations contracted slightly in the third quarter, having increased strongly in the first two quarters in the interest of maintaining essential business operations, before remaining broadly stable in October and November. However, the further intensification of the pandemic suggests downside risks to investment in the first quarter of 2021.

Housing investment (proxied by real residential investment) recovered strongly in the third quarter, increasing by 12.3% quarter on quarter, following a cumulative decline of 14.3% in the first half of 2020, and is expected to remain subdued in the short term. That recovery was particularly strong in the large euro area countries that were most affected by lockdowns during the first wave of the pandemic, with Italy, France and Spain seeing substantial increases of 45.0%, 30.6% and 15.7% respectively. In Germany, meanwhile, housing investment declined by 2.0% in the third quarter. Activity tended, overall, to be driven by firms working their way through a large backlog of construction plans, with construction sites reopening and new building projects being launched. However, the short-term outlook for housing investment remains subdued, with the backlog of orders dwindling and new business activity drying up as countries increase restrictions in order to contain the spread of the virus. Indeed, the euro area PMI for construction output remained below the expansionary threshold in the fourth quarter, declining further quarter on quarter in average terms. Meanwhile, construction production increased by just 1.4% month on month in November, pointing to an overall slowdown in quarter‑on‑quarter terms in the fourth quarter and suggesting that housing investment might be following a similar trend. Looking further ahead, despite some slight improvements in the fourth quarter of 2020, firms’ expectations continue to point to weak developments over the short term.

Following the rebound in euro area trade seen in the third quarter, growth in trade has moderated. November data on nominal trade in goods confirm that growth in extra‑ and intra-euro area trade has moderated since September, but the process of returning to pre-pandemic levels of trade is continuing, with growth rates higher than those seen in the two years to February 2020 (with extra-euro area imports and exports around 4.5% below pre-pandemic levels, and intra-euro area trade around 3.2% lower). Euro area imports and exports have increased in all sub-categories since April 2020, especially exports to the United Kingdom (in part as a consequence of UK stockpiling of goods ahead of Brexit) and exports to China. Consumption goods (especially cars and fuel) have seen a robust expansion, boosted by strong Chinese demand for German goods. Conversely, the weakness of private investment has dampened trade in capital goods and will continue to weigh on activity until uncertainty surrounding the rolling-out of vaccines and the evolution of the pandemic dissipates. While it has been less affected than capital goods, trade in intermediate goods (which remains subdued) tends to shape the overall picture, as it accounts for the bulk of total flows (especially for intra-euro area trade). Leading indicators point to further improvements at the end of the year, including improvements to trade in services (which is still very depressed). Indeed, the PMI for new service export orders suggests that the situation improved slightly in December as the winter holiday season kicked in.

Economic indicators (particularly survey results) suggest that output may well contract in the fourth quarter of 2020, reflecting the strengthening of containment measures. Industrial production (excluding construction) increased by 2.5% month on month in November, meaning that the average level of production in the first two months of the fourth quarter was 3.8% higher than the average for the third quarter. However, if we look at more recent survey data, we can see that the composite output PMI fell to 48.1 in the fourth quarter, down from 52.4 in the third quarter, thus indicating a contraction in output. This decline was explained entirely by developments in the service sector, while the manufacturing sector displayed a small improvement. This is not surprising and reflects services’ greater sensitivity to social distancing measures. While growth will be weak – and very possibly negative – in the fourth quarter, the relatively resilient industrial sector points to some upside risks to growth. High‑frequency indicators also point to a slowdown in the fourth quarter.

Looking ahead, the roll-out of vaccines, which started in late December, allows for greater confidence in the resolution of the health crisis. However, it will take time for widespread immunity to be achieved, and further adverse developments relating to the pandemic cannot be ruled out. While uncertainty surrounding COVID‑19 is likely to dampen the recovery in the labour market and weigh on consumption and investment, the economic recovery in the euro area should be supported by favourable financing conditions, an expansionary fiscal stance and a recovery in demand as containment measures are lifted and uncertainty recedes. The results of the latest round of the Survey of Professional Forecasters (which was conducted in early January) show that private sector GDP growth forecasts have been revised downwards for 2021 and upwards for 2022 relative to the previous round (which was conducted in early October). Forecasters foresee a 2.5% decline in GDP in the final quarter of 2020, followed by flat growth in the first quarter of 2021. This is somewhat more pessimistic than the short-term outlook entailed by the December 2020 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, which foresaw a 2.2% decline in the fourth quarter, followed by a 0.6% increase in the first quarter of 2021.That revision is consistent with increased pessimism regarding the short-term outlook on account of the intensification of containment measures, together with some rising hope regarding medium-term prospects on the back of expectations of a safe and successful start to the vaccination process.

4 Prices and costs

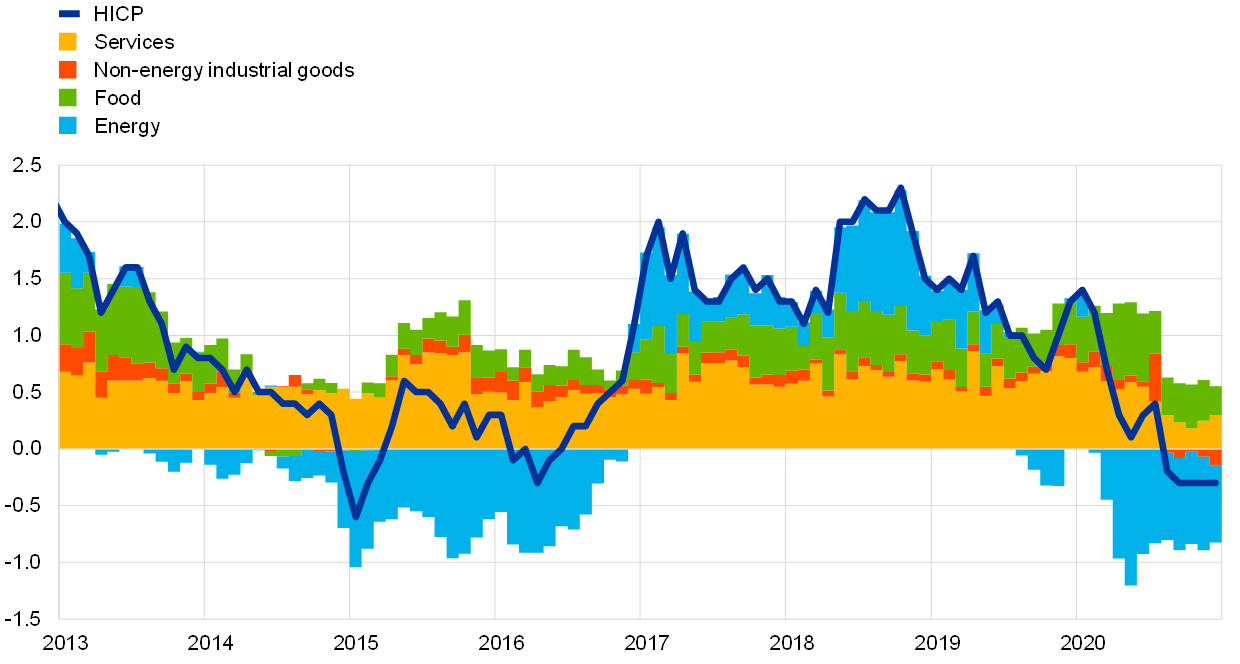

Headline inflation remained unchanged for the fourth consecutive month in December 2020 at -0.3%. The unchanged inflation rate of -0.3% in December masks movements in the main components: while energy and services inflation increased, food inflation and non-energy industrial goods (NEIG) inflation decreased (Chart 7). Despite the recent increase, energy inflation remained deep in negative territory at ‑6.9%, representing a still substantial drag on HICP inflation. Most HICP sub-indices in December were considered reliable by Eurostat, although the share of price imputations has risen again owing to new containment and lockdown measures.

Chart 7

Contributions of components of euro area headline HICP inflation

(annual percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for December 2020. Growth rates for 2015 are distorted upwards owing to a methodological change (see the box entitled “A new method for the package holiday price index in Germany and its impact on HICP inflation rates”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2, ECB, 2019).

Measures of underlying inflation remained broadly unchanged at low levels. HICP inflation excluding energy and food (HICPX) remained unchanged for the fourth consecutive month at a historical low of 0.2% in December. The unchanged inflation rate conceals a decline in NEIG inflation to -0.5% in December from -0.3% in November and a slight increase in services inflation to 0.7% from 0.6% over the same period. The decline in NEIG inflation was mainly due to the clothing and footwear component, while the increase in services inflation was largely due to a modest reversal of the substantial declines in travel-related services inflation (see Box 6). Other measures of underlying inflation remained broadly stable at low levels in December. The low levels also continued to reflect the temporary reduction in German VAT rates during the second half of 2020 (Chart 8).

Chart 8

Measures of underlying inflation

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations based on estimates in “Impact of the temporary reduction in VAT on consumer prices”, Monthly Report, Deutsche Bundesbank, November 2020.

Notes: The latest observations are for December 2020. HICPXX stands for HICP excluding energy, food, travel-related items and clothing and footwear.

Pipeline price pressures for NEIG inflation increased in the early stages of the supply chain, albeit from generally low levels. Domestic producer price inflation for non-food consumer goods was 0.7% in November, unchanged from the previous month and continuing to hover slightly above its long-term average, while import price inflation for non-food consumer goods remained negative, partly owing to past euro appreciation, albeit increasing marginally to -1.1% in November from -1.2% in October. At the earlier input stages, inflation for intermediate goods increased substantially in November: domestic producer price inflation increased to -0.6%, from -1.3% in the previous month, while import price inflation increased to -1.6% from ‑2.4% over the same period. This may in part reflect some easing in downward pressures from the euro effective exchange rate and oil prices and a further strengthening in upward pressures from prices for other commodities.

Output price inflation as measured by the GDP deflator declined in the third quarter of 2020. The annual growth rate of the GDP deflator declined to 1.1% in the third quarter of 2020 from 2.4% in the previous quarter. This mainly reflected the impact of a sharp decline in unit labour cost growth as less negative labour productivity growth, which was boosted by a strong pick-up in GDP growth, outweighed a strengthening of compensation per employee growth.[5] A lower recourse to short-time work schemes in view of the rebound in economic activity not only supported compensation per employee growth but, via lower subsidies, also implied an easing of the negative contribution from net indirect taxes to the GDP deflator. At the same time, reflecting the pick-up in economic activity, profit margins increased compared to the previous quarter, although their contribution was still negative.

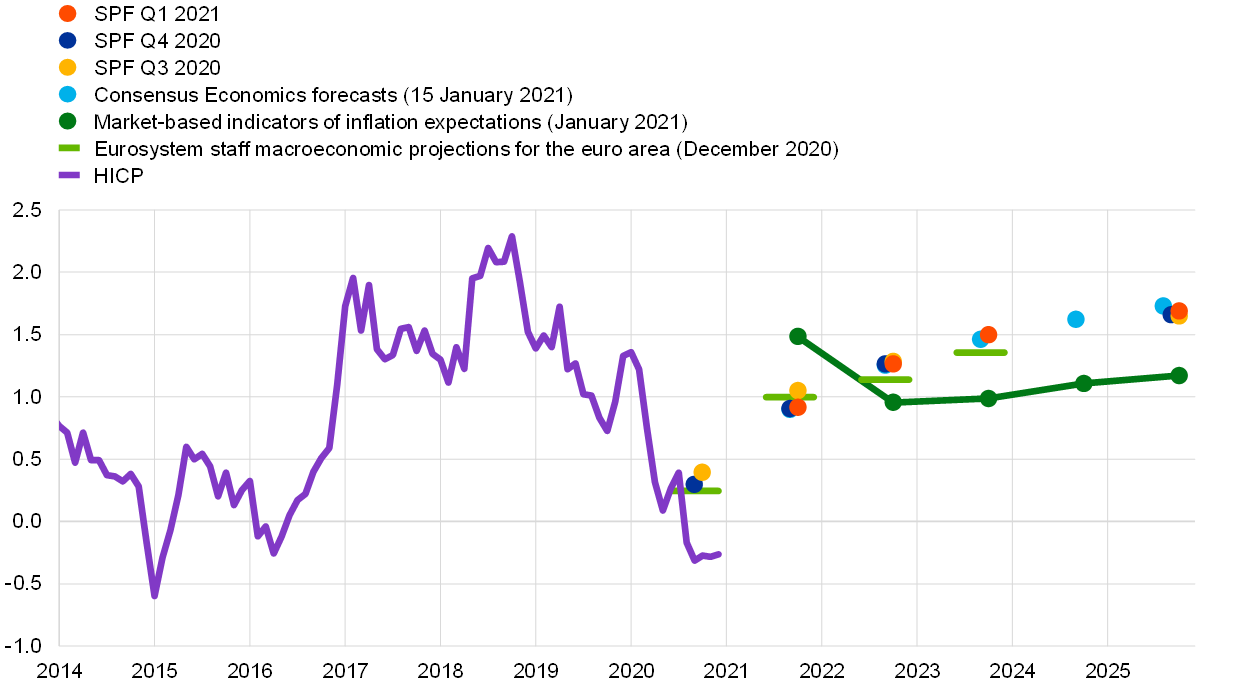

Market-based indicators of medium to longer-term inflation expectations in the euro area increased, but still remained at very subdued levels, while survey-based indicators of inflation expectations were broadly stable at low levels (Chart 9). Movements in inflation markets remained limited, with an uptick taking place in mid-January. Since the Governing Council meeting on 10 December, the most prominent indicator of longer-term market-based inflation expectations, the five-year forward inflation-linked swap (ILS) rate five years ahead, has risen by 6 basis points to 1.32%, slightly above its pre-pandemic level (1.25%). Nevertheless, current levels of longer-term forward ILS rates continue to be very subdued and do not suggest a return of inflation to the ECB’s aim in the foreseeable future. Survey-based indicators of longer-term inflation expectations were unchanged or increased slightly, but remained at low levels. According to the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) for the first quarter of 2021, conducted in early January 2021, longer-term inflation expectations were unchanged at 1.7%. Longer-term inflation expectations as measured by Consensus Economics in January were also 1.7%, up slightly from 1.6% in the previous round in October.

Chart 9

Market and survey-based indicators of inflation expectations

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF), Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area (December 2020) and Consensus Economics (15 January 2021).

Notes: The SPF for the first quarter of 2021 was conducted between 7 and 11 January 2021. The market-implied curve is based on the one-year spot inflation rate and the one-year forward rate one year ahead, the one-year forward rate two years ahead, the one-year forward rate three years ahead and the one-year forward rate four years ahead. The latest observations for market-based indicators of inflation expectations are for 19 January 2021.

5 Money and credit

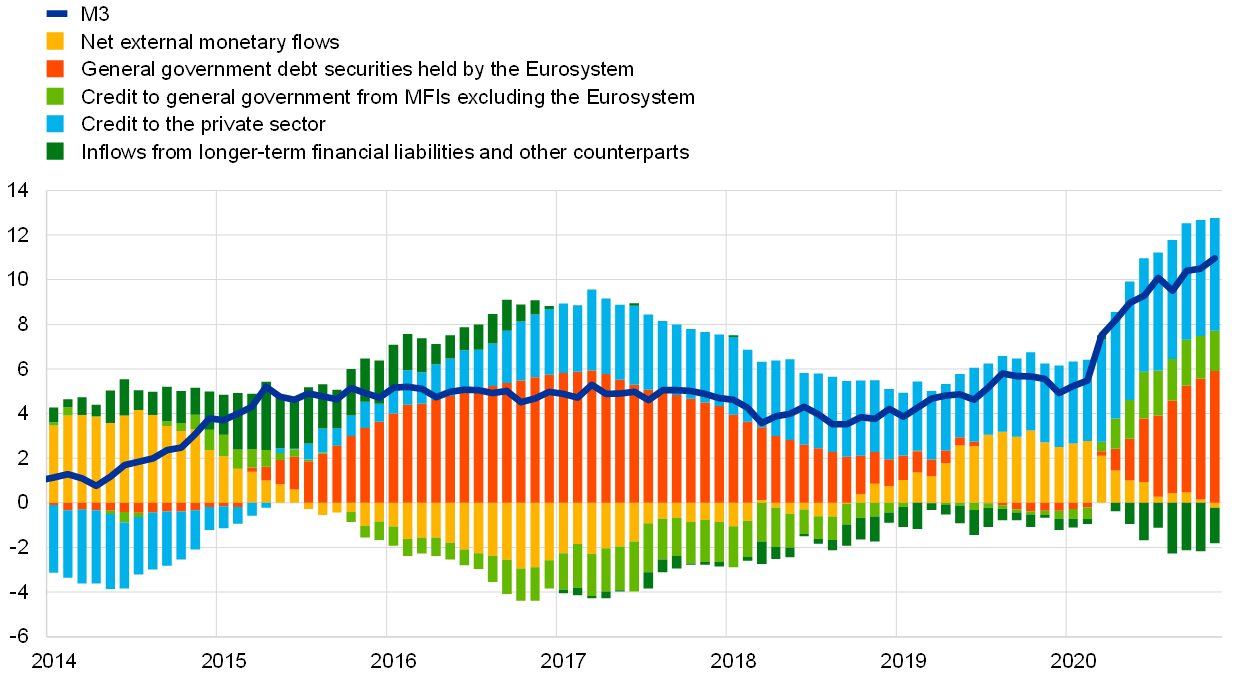

Broad money growth increased further in November 2020. The annual growth rate of M3 rose to 11.0% in November, after 10.5% in October (Chart 10). While the coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis has triggered an exceptional preference for liquidity, the strong growth in broad money is, to a large extent, reflecting the sizeable support measures taken by the ECB and supervisory authorities, as well as by national governments, to ensure that sufficient liquidity is provided to the economy to address the economic consequences and uncertainties stemming from the crisis. In November, a further contributing factor was higher net spending by governments from the deposit buffers accumulated in previous months, as these deposits are not part of M3. The use of these buffers reflected the tightening of COVID-related restrictions and the reactivation of fiscal support measures in a month with broadly zero net borrowing by governments. The increase in M3 was mainly driven by the narrow aggregate M1, which includes the most liquid components of M3. The annual growth rate of M1 increased to 14.5% in November, after 13.8% in October. This development was mainly attributable to the strong annual growth in overnight deposits held by firms and households, for which an important driver was a strong preference for liquidity. Other short-term deposits and marketable instruments continued to make a small contribution to annual M3 growth, mirroring the low level of interest rates and the search-for-yield behaviour of investors.

Domestic credit has remained the main source of money creation. The Eurosystem’s net purchases of government securities under the ECB’s asset purchase programme (APP) and the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) made the largest contribution to M3 growth in November 2020 (red portion of the bars in Chart 10). Credit to the private sector lost some momentum but continued to provide the second largest contribution to M3 growth (blue portion of the bars in Chart 10). Further support to M3 growth came from credit to general government from monetary financial institutions (MFIs) excluding the Eurosystem (light green portion of the bars in Chart 10), but the respective flows have moderated recently. As in previous months, the contribution from annual net external monetary flows remained negligible in November (yellow portion of the bars in Chart 10), while longer-term financial liabilities and other counterparts dampened broad money growth. This was due to developments in other counterparts (repurchase agreements, in particular), while favourable conditions on targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs) continued to support banks’ funding substitution, resulting in net redemptions in long-term bank bonds.

Chart 10

M3 and its counterparts

(annual percentage changes; contributions in percentage points; adjusted for seasonal and calendar effects)

Source: ECB.

Notes: Credit to the private sector includes monetary financial institution (MFI) loans to the private sector and MFI holdings of securities issued by the euro area private non-MFI sector. As such, it also covers the Eurosystem’s purchases of non-MFI debt securities under the corporate sector purchase programme and the PEPP. The latest observation is for November 2020.

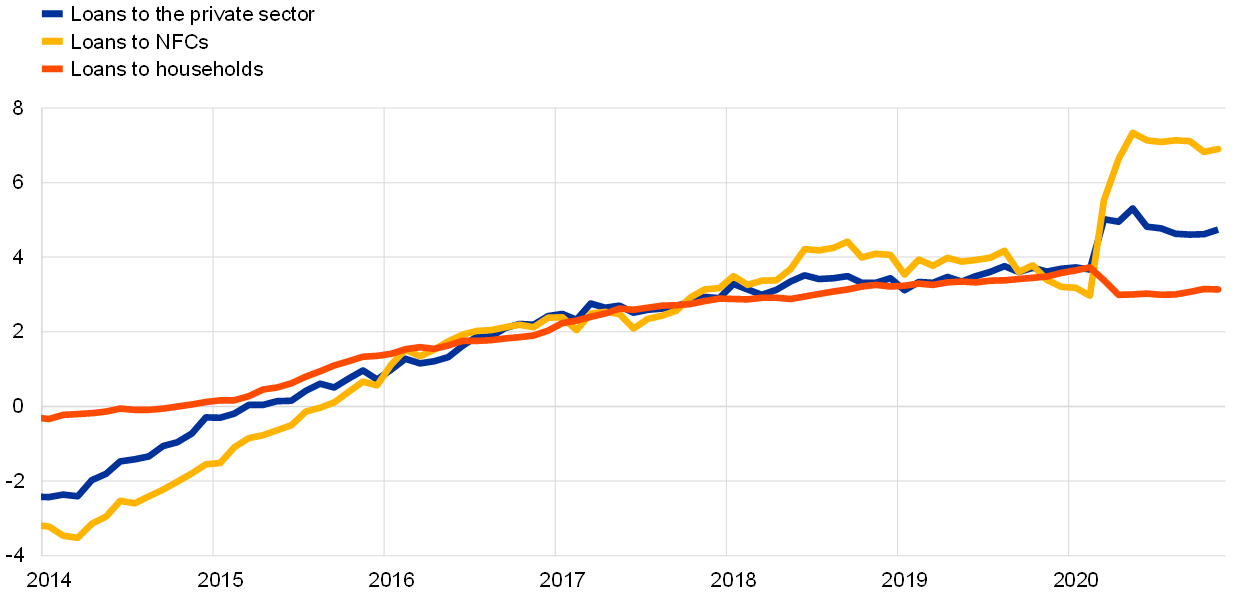

Growth in loans to the private sector remained stable in November 2020. The annual growth rate of bank loans to the private sector stood at 4.7% in November, broadly unchanged since June (Chart 11). The pattern of broadly stable lending to households and moderating lending to firms since the end of the summer has continued. This shift is being driven by the specific nature of the COVID-19 crisis, which led to a collapse in corporate cash flows and compelled firms to step up significantly their reliance on external financing during the first phase of the crisis. In November loans to non-financial corporations (NFCs) were broadly unchanged at 6.9%, while monthly lending flows to NFCs continued to moderate. The moderation in borrowing by firms from banks since the summer has coincided with lower recourse to government guarantees, which may signal that firms’ emergency liquidity needs are diminishing. Annual growth in loans to households remained almost unchanged at 3.1% in November, after 3.2% in October. Mortgage lending continued to drive household borrowing, while growth in consumer credit weakened in November, in line with a tightening of COVID-related restrictions.

Chart 11

Loans to the private sector

(annual growth rate)

Source: ECB.

Notes: Loans are adjusted for loan sales, securitisation and notional cash pooling. The latest observation is for November 2020.

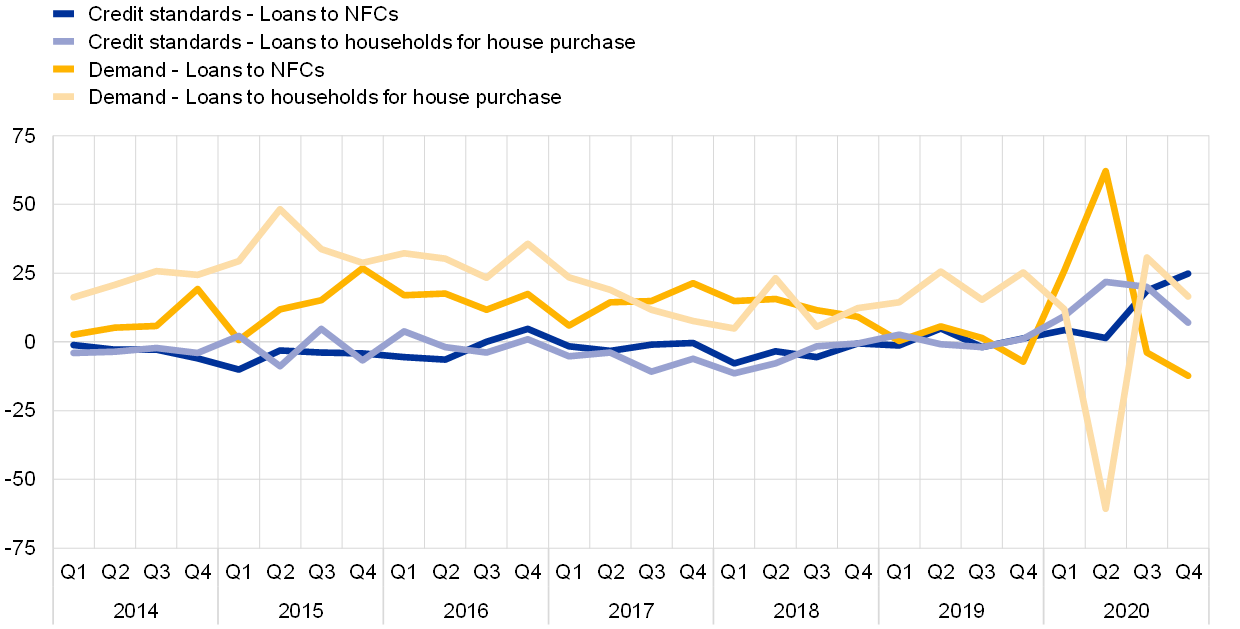

The January 2021 euro area bank lending survey shows that the tightening of credit standards for loans to firms and to households continued in the fourth quarter of 2020 in the context of renewed COVID-related restrictions (Chart 12). Credit standards on loans to firms tightened in the fourth quarter of 2020, mainly driven by heightened risk perceptions (related to the deterioration in the general economic outlook and the firm-specific situation). For the first quarter of 2021, banks expect a further net tightening of credit standards for firms. Credit standards for housing loans and for consumer credit continued to tighten in the fourth quarter of 2020 but at a slower pace than in the previous quarters of 2020. Firms’ demand for loans or drawing of credit lines declined in the fourth quarter of 2020, after a continued net increase in demand for inventories and working capital in previous quarters, which reflected firms building up precautionary liquidity buffers. By contrast, net demand for housing loans increased in the fourth quarter, supported by the low general level of interest rates and, to a lesser extent, improving housing market prospects, while net demand for consumer credit declined. Banks expect a further moderate net tightening of credit standards for households and a slight decline in housing loan demand in the first quarter of 2021. Banks also indicated that COVID-related government guarantees were important in supporting banks’ credit standards and terms and conditions for loans to firms – both SMEs and large enterprises – in 2020. Euro area banks’ access to retail and wholesale funding generally improved in the fourth quarter of 2020. Euro area banks also indicated that their access to debt securities funding and securitisation continued to improve in the fourth quarter of 2020. At the same time, they highlighted a continued strengthening of their capital position against the backdrop of regulatory and supervisory actions in the second half of 2020 and a net tightening of their credit standards for loans to enterprises and for consumer credit on account of non-performing loan ratios.

Chart 12

Changes in credit standards and net demand for loans (or credit lines) to enterprises and to households for house purchase

(net percentages of banks reporting a tightening of credit standards or an increase in loan demand)

Source: ECB (euro area bank lending survey).

Notes: For the bank lending survey questions on credit standards, ”net percentages” are defined as the difference between the sum of the percentages of banks responding “tightened considerably” or “tightened somewhat” and the sum of the percentages of banks responding “eased somewhat” or “eased considerably”. For the survey questions on demand for loans, “net percentages” are defined as the difference between the sum of the percentages of banks responding “increased considerably” or “increased somewhat” and the sum of the percentages of banks responding “decreased somewhat” or “decreased considerably”. The latest observation is for the fourth quarter of 2020.

Favourable lending rates have continued to support euro area economic growth. Lending rates have stabilised at their historical lows, reflecting the continued impact of the measures taken by the ECB, supervisors and governments to support credit supply conditions. In November 2020 the composite bank lending rates for loans to NFCs and households remained broadly unchanged at 1.50% and 1.35% respectively (Chart 13). This development was widespread across euro area countries. Moreover, the spread between bank lending rates on very small loans and those on large loans stabilised at levels below those observed before the start of the pandemic. At the same time, the severe economic impact of the resultant crisis on firms’ revenues, households’ employment prospects and overall borrower creditworthiness, as reflected in the bank lending survey, may put upward pressure on bank lending rates. Therefore, policy support – notably the expansion of the PEPP and the recalibration of TLTRO III adopted in December 2020 – will help to limit upward pressures on bank lending rates in a difficult and uncertain economic environment.

Chart 13

Composite bank lending rates for NFCs and households

(percentages per annum)

Source: ECB.

Notes: Composite bank lending rates are calculated by aggregating short and long-term rates using a 24-month moving average of new business volumes. The latest observation is for November 2020.

Boxes

1 Pandemic-induced constraints and inflation in advanced economies

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic had a severe and extraordinary impact on the global economy during the first half of 2020. Economic activity across advanced economies was severely affected, and consumer price inflation declined on the back of these developments. The pandemic weighed on not only headline inflation but also underlying inflation measures, such as consumer price inflation excluding food and energy, which declined during the initial lockdowns and gradually rebounded thereafter. This pattern was shaped by the confluence of two key forces triggered by the crisis: weak demand and constrained supply. This box uses granular data on consumer spending and prices, together with a structural analysis using Bayesian Vector Autoregression (BVAR) models, to study their relative impact on inflation in key advanced economies outside the euro area.[6]

More2 Rotation towards normality – the impact of COVID-19 vaccine-related news on global financial markets

The outbreak of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic led to a synchronised sell-off of global risky assets, followed by an uneven recovery across sectors and countries. The stock market recovery was characterised by investors rebalancing away from countries and sectors hit by the pandemic, including airlines, tourism and energy, towards those perceived to benefit from the crisis, most notably IT and communications services, as well as pharmaceutical firms. Across countries, the pre-pandemic sector composition of the stock market explains the bulk of the differences in equity market performances in 2020 (Chart A, upper panel).

More3 The economic impact of the pandemic – drivers of regional differences

This box examines the drivers of intra-country regional differences in the economic impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19), as observed in the four largest euro area economies during the initial phase of the pandemic. More specifically, it discusses the role played by sectoral structure and trade linkages in explaining the difference in terms of how COVID-19 affects the regions within these countries economically.

More4 Model-based risk analysis during the pandemic: introducing ECB-BASIR

The interplay between epidemiological fundamentals of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, containment policies and the macroeconomy can be assessed by combining a macroeconomic model with an epidemiological model. ECB‑BASIR[7] is an extension of the ECB-BASE[8] model which addresses specific features of the COVID-19 crisis by combining a standard pandemic susceptible-infected-recovered (SIR) model with a semi-structural large-scale macroeconomic model. An SIR model – a compartmental model introduced by Kermack and McKendrick[9] – divides the population into groups and, using differential equations, predicts how a disease will spread on the basis of the number of susceptible, infected, recovered or deceased individuals. We extend that model by incorporating two additional categories: (i) quarantined individuals, and (ii) people who have been vaccinated (who are assumed to be immune to the virus). We postulate that economic behaviour will affect the transmission of the disease (with declines in consumption and work activity reducing the probability of people getting infected, for example), establishing a channel from the macroeconomic model to the epidemiological model through the sensitivity of transmission to economic interaction between people. The channel running in the opposite direction, from the epidemiological model to macroeconomic behaviour, is established by assuming that different groups of agents modelled in the epidemiological component have differing ability to work, consume and invest. For example, agents that are constrained by lockdowns can only consume part of what unconstrained agents consume, with those differences between the consumption of constrained and unconstrained agents being estimated on the basis of data for the first and second quarters of 2020. Those effects then propagate through the macroeconomic linkages in the model.

More5 Housing costs and homeownership in the euro area

Housing costs represent a significant share of the household budget. Housing costs typically include the utility costs (water, electricity, gas and heating), maintenance, and rental or mortgage interest payments, altogether accounting for around one-fifth[10] of household income expenditure in 2019. Changes in these costs are closely linked with housing market developments, such as rental and house prices, as well as mortgage payments. Furthermore, housing costs are dependent on structural features, which will be the focus of this box, such as the homeownership rate or certain household characteristics. This is due to the fact that tenants and less affluent households, for example, tend to spend a large share of their income on housing. Against this background, this box examines certain data that help to frame the housing cost burden in the euro area and across types of household.

More6 Prices for travel during the COVID-19 pandemic: is there commonality across countries and items?

Inflation for travel-related items has plummeted in the euro area during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Services inflation in general has deteriorated recently reaching a trough in October 2020. The main driver behind the decline has been the strong drop in inflation for travel-related services (here referring to package holidays, accommodation services, and passenger transport by air), despite its relatively moderate weight in HICP services (Chart A).[11] This likely reflects the nature of the containment and lockdown measures taken across the euro area.[12] Given that the impact of lockdown measures on inflation has been particularly visible in those countries that are heavily exposed to tourism[13], this box analyses the potential commonalities in travel-related items affected by COVID-19 lockdowns pulling down services inflation across the euro area countries.

MoreArticles

1 The ECB’s dialogue with non-financial companies

As part of the process of gathering information on the outlook for economic activity and prices, the ECB maintains regular contacts with non‑financial companies. This gathering of business intelligence has become more structured over time and tends to be particularly valuable during exceptional periods, such as those resulting from the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Therefore, starting with this issue of the Economic Bulletin, the ECB will provide a summary of the main findings from its contacts with leading euro area businesses. This article explains how these interactions contribute to the ECB’s economic analysis and how they are organised and summarised. The main findings from the most recent exchanges with companies, which took place in early January 2021, are summarised in Box 1.

More2 The role of demand and supply factors in HICP inflation during the COVID-19 pandemic – a disaggregated perspective

The economic impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is not a standard textbook shock. Instead the shock is multidimensional, with sources on both the external and the domestic side, on both the demand and the supply side, and at both the aggregate and the sector-specific level. This poses challenges for the assessment of inflation. Established relationships between inflation and its determinants may not hold up or may not be scalable, given the magnitude of disturbances in product and labour markets. Moreover, the increasing emphasis of the inflation literature on distributions rather than point outcomes for future inflation is relevant for analysing the impact that the COVID-19 shock has had on inflation risks.

More3 The initial fiscal policy responses of euro area countries to the COVID-19 crisis

This article was updated on 10 February to amend footnote 4 and the title of Chart 2 on the European Commission’s evaluation of Member States’ draft budgetary plans for 2021.

Euro area countries have relied extensively on fiscal policy to counter the harmful impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on their economies. They have implemented a broad range of measures, some with an immediate budgetary impact and others, such as liquidity measures, which, in principle, are not expected to cause an immediate deterioration in the fiscal outlook. Since all euro area countries were hit by the economic shock largely through the same channels, their fiscal responses in the early stages of the crisis were similar in terms of the instruments used. Fiscal emergency packages were mostly aimed at limiting the economic fallout from containment measures through direct measures to protect firms and workers in the affected industries. Simultaneously, extensive liquidity support measures in the form of tax deferrals and State guarantees were announced to help firms particularly impacted by the containment policies to avoid liquidity shortages. In order to support the recovery, fiscal policy needs to provide targeted and mostly temporary stimulus, tailored to the specific characteristics of the crisis and countries’ fiscal positions. Government investments, complemented by the Next Generation EU package, and accompanied by appropriate structural policies, should play a major role in this respect.

MoreStatistics

Statistical annex© European Central Bank, 2021

Postal address 60640 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Telephone +49 69 1344 0

Website www.ecb.europa.eu

All rights reserved. Reproduction for educational and non-commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

This Bulletin was produced under the responsibility of the Executive Board of the ECB. Translations are prepared and published by the national central banks.

The cut-off date for the statistics included in this issue was 20 January 2021.

For specific terminology please refer to the ECB glossary (available in English only).

ISSN 2363-3417 (html)

ISSN 2363-3417 (pdf)

QB-BP-21-001-EN-Q (html)

QB-BP-21-001-EN-N (pdf)

- The methodology for computing the EONIA changed on 2 October 2019; it is now calculated as the €STR plus a fixed spread of 8.5 basis points. See the box entitled “Goodbye EONIA, welcome €STR!”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 7, ECB, 2019.

- This assessment reflects information from the latest survey results and empirical estimates of “genuine” rate expectations, i.e. forward rates net of term premia.

- See the article entitled “The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the euro area labour market”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 8, ECB, 2020.

- See also the box entitled “COVID-19 and the increase in household savings: precautionary or forced?”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 6, ECB, 2020.

- For more information, see the box entitled “Short-time work schemes and their effects on wages and disposable income”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 4, ECB, 2020.

- For analysis of the euro area and euro area countries, see “The role of demand and supply factors in HICP inflation during the COVID-19 pandemic – a disaggregated perspective”, Monthly Bulletin, Issue 1, ECB, 2021.

- See Angelini, E., Damjanović, M., Darracq Pariès, M. and Zimic, S., “ECB-BASIR: a primer on the macroeconomic implications of the Covid-19 pandemic”, Working Paper Series, No 2431, ECB, June 2020.

- See Angelini, E., Bokan, N., Christoffel, K., Ciccarelli, M. and Zimic, S., “Introducing ECB-BASE: The blueprint of the new ECB semi-structural model for the euro area”, Working Paper Series, No 2315, ECB, September 2019.

- See Kermack, W.O. and McKendrick, A.G., “A Contribution to the Mathematical Theory of Epidemics”, Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series A, Vol. 115, No 772, August 1927, pp. 700-721.

- This includes imputed rents.

- Package holiday prices are recorded in the country where the trip starts, although the largest part of the underlying service may be provided in the travel destination. The price of the package holiday is still likely to reflect price developments for accommodation, restaurants and other similar services in the travel destination.

- It should be kept in mind that the lockdowns have led to large changes in consumer spending patterns that have not been reflected so far in official inflation statistics. For a detailed discussion of pandemic-induced changes in household consumption and their implications for inflation see the box entitled “Consumption patterns and inflation measurement issues during the COVID-19 pandemic”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 7, ECB, 2020.

- See the box entitled “Developments in the tourism sector during the COVID-19 pandemic”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 8, ECB, 2020.