Geopolitical risk and its implications for macroprudential policy

Macroprudential Bulletin 28, April 2025.

This article explores the link between geopolitical risk and bank solvency and discusses the potential implications for macroprudential policy. Drawing on 120 years of data, analysis reveals that heightened geopolitical risk has been associated with lower bank capitalisation over the past century. This effect can arise through multiple economic and financial channels, including reduced economic activity, surging inflation, increased sovereign risk, and shifts in capital flows and asset prices. However, the analysis also finds that the impact of geopolitical risk on bank solvency has been non-linear, with major geopolitical risk events having a much stronger effect than less major or more localised geopolitical shocks, with the effect being heterogenous across countries. Macroprudential policy and microprudential supervision play important and complementary roles in ensuring that banks are sufficiently prepared to absorb potential geopolitical shocks. While microprudential supervision ensures that geopolitical risk is factored into capital and liquidity planning, macroprudential capital buffer requirements can be released when shocks materialise, thereby supporting banks in absorbing losses while maintaining the provision of key financial services to the real economy.

1 Introduction

Geopolitical risk has attracted renewed attention in recent years. Geopolitical risk can be defined as “the threat, realization, and escalation of adverse events associated with wars, terrorism, and any tensions among states and political actors that affect the peaceful course of international relations”.[1] Well-known geopolitical risk events of the last 40 years include the First Gulf War in the early 1990s and the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001. While geopolitical risk was rather low by historical standards between 2018 and 2021, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the conflict in Gaza have led to renewed spikes (Chart 1).

Chart 1

Geopolitical risk has spiked again in recent years

Geopolitical risk index

(index: average 1985-2019 = 100)

Source: Caldara and Iacoviello (2022).

Geopolitical risk events can cause adverse economic developments and may endanger financial stability. Unlike other types of risk (e.g. credit risk), geopolitical risk is multi-faceted and not directly quantifiable as it arises from a range of interconnected political, economic and social factors spreading across borders and sectors. In its most extreme form (war), geopolitical risk materialisation may be associated with human losses, destruction of physical assets and corporate defaults, which may also translate into severe financial losses. However, less extreme events can also have consequences for the financial sector. For example, geopolitical risk events can push up oil/energy prices and thereby increase inflation and interest rates and reduce economic activity. Moreover, major disruptions to international trade due to wars or increasing regional political fragmentation can substantially reduce potential gross domestic product (GDP) and drag down stock market prices. Such developments can in turn amplify existing financial stability vulnerabilities or potentially trigger the materialisation of financial stability risks.[2] The currently elevated geopolitical risk thus has significant implications for financial stability and therefore also for macroprudential policy.

Against this background, this article looks in more detail at the link between geopolitical risk and bank solvency and discusses the potential implications for macroprudential policy. In Section 2 we use data from the past 120 years to show that elevated geopolitical risk usually leads to sizeable declines in bank capitalisation.[3] In Section 3 we argue that releasable macroprudential capital buffers are particularly suitable for addressing geopolitical risk in the current environment of heightened uncertainty.

2 The impact of geopolitical risk on bank solvency

2.1 Data and descriptive analysis

Data from the past 120 years show that geopolitical risk was particularly high during the two world wars and during the 1960s and 1980s. The 20th century witnessed several geopolitical crises, such as the world wars, the events of the Cold War and the conflicts in the Middle East. As the most extreme geopolitical risk events occurred decades ago, a long time series is essential to examine the potential implications of geopolitical risk for financial stability. This analysis therefore takes a very long historical perspective based on a sample of 17 countries worldwide over the period 1900-2020.[4] It combines two main data sources: the country-level geopolitical risk index (GPRC) developed by Caldara and Iacoviello (2022) and country and banking sector characteristics from Jordà et al. (2017).[5]

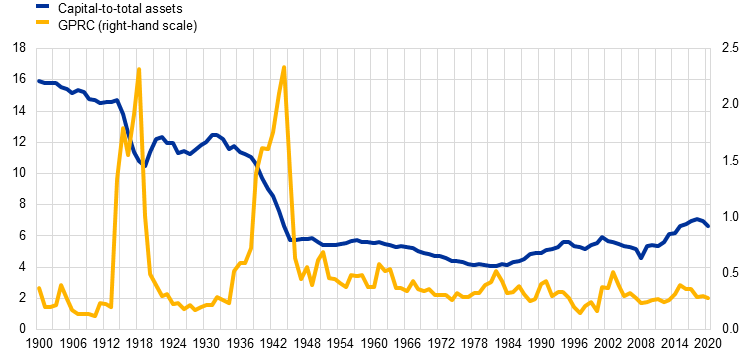

Chart 2

Bank capitalisation declined sharply during the two world wars, while the impact of other geopolitical events was weaker

Geopolitical risk and bank capitalisation

(left-hand scale: percentages; right-hand scale: index)

Sources: Behn et al. (2025), Jordà-Schularick-Taylor Macrohistory (2016), Caldara and Iacoviello (2022), and ECB calculations.

Chart 2 indicates that bank capitalisation has tended to decrease following major geopolitical risk events. Specifically, banking sector capitalisation declined sharply during the two world wars, with an average drop of 5 percentage points (Chart 2).[6] However, since the 1950s, the negative correlation between geopolitical risk and bank capitalisation seems to have weakened. Capital fell on average by 0.1 percentage points in the aftermath of the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 and by 0.2 percentage points after the 9/11 terrorist attack, while other geopolitical risk events are associated with only negligible changes in bank capitalisation. However, to isolate the impact of geopolitical risk on bank capitalisation, it is important to control for other confounding factors.

2.2 Estimation and non-linear effects

Regression analysis confirms that heightened geopolitical risk has been associated with lower bank capitalisation over the past century. Country-level panel data estimations controlling for a broad range of country and banking sector-specific characteristics reveal a negative and statistically significant relationship between the geopolitical risk index and the bank capital-to-assets ratio. In particular, a two standard deviation increase in the geopolitical risk index has been associated with a decrease in the bank capital-to-assets ratio of around 0.2 percentage points on average (Chart 3, panel a). Given the average capital-to-assets ratio of around 8%, this represents a 2.5% capital depletion.[7]

Chart 3

Heightened geopolitical risk is associated with a decline in bank capital, but the effect is non-linear and particularly pronounced for major events

a) Estimated effect of a two standard deviation increase in the geopolitical risk index on bank capitalisation | b) Estimated effect of major and less major geopolitical events on bank capitalisation |

|---|---|

(percentage points) | (percentage points) |

|  |

Sources: Behn et al. (2025), Jordà-Schularick-Taylor Macrohistory (2016), and Caldara and Iacoviello (2022).

Notes: See footnotes for information about the model specification and variables construction. Confidence intervals are at the 95% level.

The impact of geopolitical risk on bank solvency has been non-linear, with major geopolitical risk events exerting a much stronger effect. Estimates capturing differential effects of major and less major geopolitical risk events on bank capitalisation suggest that only large-scale crises may pose an immediate threat to financial stability.[8] All else being equal, major geopolitical events like the two world wars led to a statistically significant decline in bank capitalisation of 0.53 percentage points, whereas less major events, despite also having a negative and significant effect, resulted in a much smaller 0.07 percentage point contraction (Chart 3, panel b). These findings indicate that only extreme geopolitical shocks have the potential to undermine bank solvency and financial stability directly, while more localised or moderate events are unlikely to push banks into distress (although they may, of course, further aggravate adverse developments). Moreover, the results highlight the importance of sufficient data availability and methodological considerations when assessing the financial stability implications of geopolitical risk, as most datasets do not capture episodes of large-scale geopolitical turmoil.

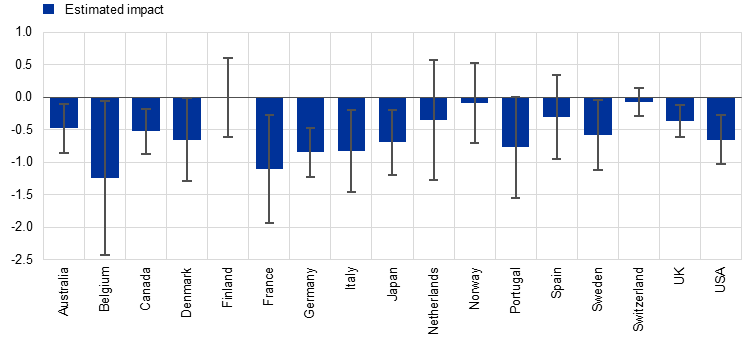

The impact of major geopolitical risk events can also vary significantly across countries. Econometric estimates capturing the effect of major geopolitical risk events on bank capitalisation across countries indicate a stronger capital contraction in some countries, with other countries experiencing a negligible or statistically insignificant impact on bank capitalisation. During major geopolitical shocks, countries like France, Germany, Italy and Belgium that were at the epicentre of the most extreme events in the 20th century – i.e. the two world wars – faced an average capital contraction of about 1 percentage point, while in countries like Australia, Canada, Finland, Norway, Spain and Switzerland the contraction was smaller or not statistically significant (Chart 4).[9]

Chart 4

The effect of major geopolitical risk on bank capitalisation varies across countries

(percentage points)

Sources: Jordà-Schularick-Taylor Macrohistory (2016), Caldara and Iacoviello (2022) , and ECB calculations.

Notes: See footnotes for information about the model specification and variables construction. The country-level coefficients are the sums of the individual coefficients for major geopolitical risk events (high GPRC) and the interaction term between high GPRC and country dummies. Confidence intervals are at the 95% level.

3 Implications for macroprudential policy

The findings above illustrate that geopolitical risk can have a substantial impact on bank capital and is thus relevant to ensuring sufficient resilience. As geopolitical risk is multi-faceted, the prudential response also needs to be multi-faceted. Microprudential supervision and macroprudential policy already take the risk into account in various ways. First and foremost, micro- and macroprudential capital requirements address potential losses that may result from adverse shocks, including geopolitical shocks. Geopolitical risk drivers also feed into various supervisory activities, such as those aimed at ensuring adequate governance structures and risk management practices, strengthening operational resilience and cyber defences, and ensuring that risks are properly factored into capital and liquidity planning.[10]

Releasable macroprudential capital buffers are particularly suitable for addressing geopolitical risk in the current environment of heightened uncertainty. The main benefit of such buffers is that they can be released when shocks materialise, which in turn can support banks in absorbing losses while maintaining the provision of key financial services to the real economy.[11] Moreover, releasable buffers are generally set at the banking system level and thus match the scope of geopolitical shocks that are likely to hit many banks simultaneously. Against this background, the raising of releasable macroprudential capital buffer requirements by many banking union authorities in recent years is a welcome development.[12] Besides addressing relevant macro-financial vulnerabilities, these buffers take into account the enhanced geopolitical risk environment and the possibility of further adverse shocks.[13]

Overall, macroprudential policy and microprudential supervision play important and complementary roles in ensuring that banks are sufficiently prepared to absorb potential geopolitical shocks. A coordinated and cooperative approach across policy areas and jurisdictions is essential to ensure that risks are properly addressed and information is shared effectively. At the same time, the primary responsibility for mitigating the risk remains at the political or broader economic level.

This definition of geopolitical risk is taken from Caldara, D. and Iacoviello, M. (2022), “Measuring geopolitical risk”, American Economic Review, Vol. 112, No 4, pp. 1194-1225.

For a more detailed exposition of how geopolitical risk can affect euro area financial stability, see, for example, Dieckelmann, D., Kaufmann, C., Larkou, C., McQuade, P., Negri, C., Pancaro, C. and Rößler, D. (2024), “Turbulent times: geopolitical risk and its impact on euro area financial stability”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, May, Special Feature A.

The empirical analysis presented in this article builds on the findings in Behn, M., Lang, J.H. and Reghezza, A. (2025), “120 years of insight: Geopolitical risk and bank solvency”, Economics Letters, Vol. 247, February.

The countries included in the sample are Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The country-level geopolitical risk index by Caldara and Iacoviello (2022) is derived from international press publications and provides a monthly measure of geopolitical risk at the country level since 1900. Jordà, Ò., Schularick, M. and Taylor, A.M. (2016), “Macrofinancial History and the New Business Cycle Facts”, NBER Working Paper, No 22743, October, provide a microhistory database covering 18 advanced economies since 1870 on a yearly basis.

A decline in bank capitalisation can be due to bank losses (which reduce bank equity) or an expansion of bank assets. It is likely that human losses, destruction of physical assets and corporate defaults during the world wars resulted in bank losses, thereby lowering bank equity, while the governments’ need to finance the war is likely to have led to an expansion of bank balance sheets. See Amrein, S. (2025), “Two World Wars: Overturning Conventions”, in “Capital in Banking: The Role of Capital in Banking in the 19th and 20th Century: The United Kingdom, the United States and Switzerland”, Studies in Macroeconomic History, Cambridge University Press, December, pp. 82-120. It is also likely that equity issuance was hampered during the world wars, thereby undermining capital restoration.

The estimations regress the bank capital-to-assets ratio on the geopolitical risk index and include a large set of country and banking sector-specific characteristics as controls, such as the growth rate of GDP per capita, the inflation rate, the level of the long-term interest rate, the logarithm of a country’s population, the logarithm of GDP per capita, credit growth, the loan-to-deposit ratio and the ratio of total assets minus capital and deposits to total assets minus capital. All variables are lagged by one year to take into account possible endogeneity with the capital-to-assets ratio. The estimations take into account persistence in the level of capitalisation by including the lagged dependent variable as a control in the regression. All the regressions include country and year fixed effects. Standard errors are robust to heteroskedasticity.

Major (high GPRC) and less major (medium GPRC) geopolitical events are captured by two dummy variables. The high GPRC variable takes the value 1 if a country’s geopolitical risk index is equal to or above the 90th percentile, and 0 otherwise. The medium GPRC variable takes the value 1 if a country’s geopolitical risk index is equal to or above the 50th but below the 90th percentile, and 0 otherwise. In this specification, we replace year fixed effects with decade fixed effects to compare the impact of high and medium geopolitical risk relative to low geopolitical risk within the same decade, rather than within the same year, as it is less likely that geopolitical risk will vary across all three categories within the same year.

The coefficient for Germany is likely to be downward biased, as data on bank capital-to-total assets ratios in Germany are missing for part of the Second World War.

For further details, see Buch, C. (2024), “Global rifts and financial shifts: supervising banks in an era of geopolitical instability”, speech at the eighth European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) annual conference on “New Frontiers in Macroprudential Policy”, Frankfurt am Main, 26 September.

For the experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, see, for example, Couaillier, C., Reghezza, A., Rodriguez d’Acri, C. and Scopelliti, A. (2022), “How to release capital requirements during a pandemic? Evidence from euro area banks”, Working Paper Series, No 2720, ECB, September.

For a recent overview of the build-up of releasable macroprudential buffers, see, for example, ECB/ESRB (2025), “Using the countercyclical capital buffer to build resilience early in the cycle – joint ECB/ESRB report on the use of the positive neutral CCyB in the EEA”, January.

See also ECB (2024), “Governing Council statement on macroprudential policies”, 28 June.