- 25 February 2021

- RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 81

Nothing compares to your loan officer – continuity of relationships and loan renegotiation

Loan renegotiations are expected to surge following the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak and the subsequent crisis, as more loans default during recessions. At such times, managing lending relationships effectively becomes even more important for bank governance, risk, and credit supply. My study presents evidence that continuous lending relationships between bank loan officers and corporate borrowers improve the outcomes of loan renegotiations. The analysis draws on a novel dataset on corporate loans during a bank reorganisation in Greece in the mid-2010s. This dataset allows us to empirically identify the causal effect of interrupted relationships. My main findings are that firms that experience an exogenous interruption in their loan officer relationship are faced with three consequences. First, the firms are less likely to renegotiate a loan compared to firms with continuous relationships. Second, when loans are renegotiated, firms with interrupted loan officer relationships receive tougher loan terms. Third, these firms raise more equity, reduce their overall borrowing, and partially substitute borrowing from other banks. These results point to the importance of lending relationships in mitigating the cost of distress for borrowers renegotiating loans. It therefore suggests that bank managers, supervisors, and resolution authorities need to be mindful of the potential costs of changing loan officers.

Introduction

How important are relationships with bank loan officers for corporate borrowers? Could stronger relationships help a firm secure better loan terms in a renegotiation? Firms in the euro area rely to a large extent on loans from credit institutions. Such loans account for approximately 30% of euro area firms’ total liabilities and approximately 85% of their total credit. At the same time, bank financing is mostly mediated by loan officers. For that reason, the relationship between a loan officer and a firm is expected to affect the issuance and renegotiation of a loan.

Whether the benefits of these relationships offset the costs is a challenging question. On the one hand, such relationships can reduce asymmetric information and improve loan monitoring. On the other hand, they may contribute to “evergreening” behaviour and potentially to an increase in non-performing loans. Evergreening means rolling over loans to firms at a high risk of bankruptcy in order to avoid losses. I study these trade-offs by looking at interruptions in relationships between loan officers and borrowing firms and their implications for loan renegotiations and firms’ sources of financing.

The central finding of the paper is that relationships between loan officers and firms do have a significant positive impact on loan renegotiation. In this study firms with interrupted relationships are less likely to renegotiate a loan compared to firms with continuous relationships. When renegotiation does occur, firms with interrupted loan officer relationships receive less beneficial loan terms – significantly shorter maturities and higher collateral requirements – even though interest rates hardly increase. Lastly, firms alter their capital structure and sources of financing after the relationship with the loan officer is interrupted.

Interruption of bank lending relationships

Lending relationships between loan officers and borrowers may be interrupted as a consequence of bank mergers and consolidations, interventions by banking supervisors, fintech developments or regular staff rotation policies. The most common reason for an interrupted lending relationship is the closure of a branch. For example, banks often consolidate their branch networks in response to financial distress, as consolidation reduces operating costs and centralises lending decisions. A banking merger can magnify this effect, as it often leads to the closure of a significant number of branches. Banking supervisors can give input on such branch closures, as they review bank mergers to ensure the safety and soundness of the new entity, including its governance and business models. Moreover, the development of fintech allows banks to move towards business models that rely less on branches and more on online communication with customers. Last but not least, the relationship between a loan officer and a firm can be interrupted if a bank applies a loan officer rotation policy. A policy of this type may be recommended as a measure to prevent excessively favourable treatment of borrowers, or evergreening behaviour by loan officers[2].

There are two main challenges for accurately estimating the impact of lending relationships on loan renegotiation. First, it is difficult to quantify the value of personal relationships. No direct measure of the value of a relationship exists. The length of a given relationship may seem like a straightforward measure, but the many inter-related factors influencing the decision to sever an existing relationship make it hard to interpret the effect. These inter-related factors create a second challenge. A bank’s decision to break an existing relationship may reflect its perception of the declining creditworthiness of the borrower. Under some circumstances a successful firm may seek to broaden its access to external finance by weakening its relationship with a particular bank. Such a decision reflects a choice by the firm and would bias any results estimated by treating relationships as if they are entirely unaffected by the firm’s actions.

To overcome these challenges, in Papoutsi (2021) I use confidential data on corporate loans from a major Greek bank, that is representative of the Greek banking sector, around the time of a large-scale reorganisation[3]. The reorganisation of the bank gives rise to variation in the length of the relationships between loan officers and firms that is exogenous, i.e. not influenced by any actions by the firms. Meanwhile the detailed confidential data on corporate loans allow us to quantify accurately the effect of interrupted relationships. During the reorganisation, some bank units are closed and the loan accounts from those units are merged with accounts in other, surviving units. A bank unit closure interrupts the relationships between loan officers and firms, because merged accounts are assigned to new loan officers. Thus, after the reorganisation, two types of firms are identified. First, there are firms whose loans have been transferred to another unit and whose loan officer relationship has consequently been discontinued. Second, there are firms that have remained assigned to the same unit. Hard information passes from one loan officer to another during transfers, because the transfer happens within the same bank. Therefore any differences observed between the two groups after the consolidation period should be the consequence of interrupted relationships.

Impact on loan renegotiation

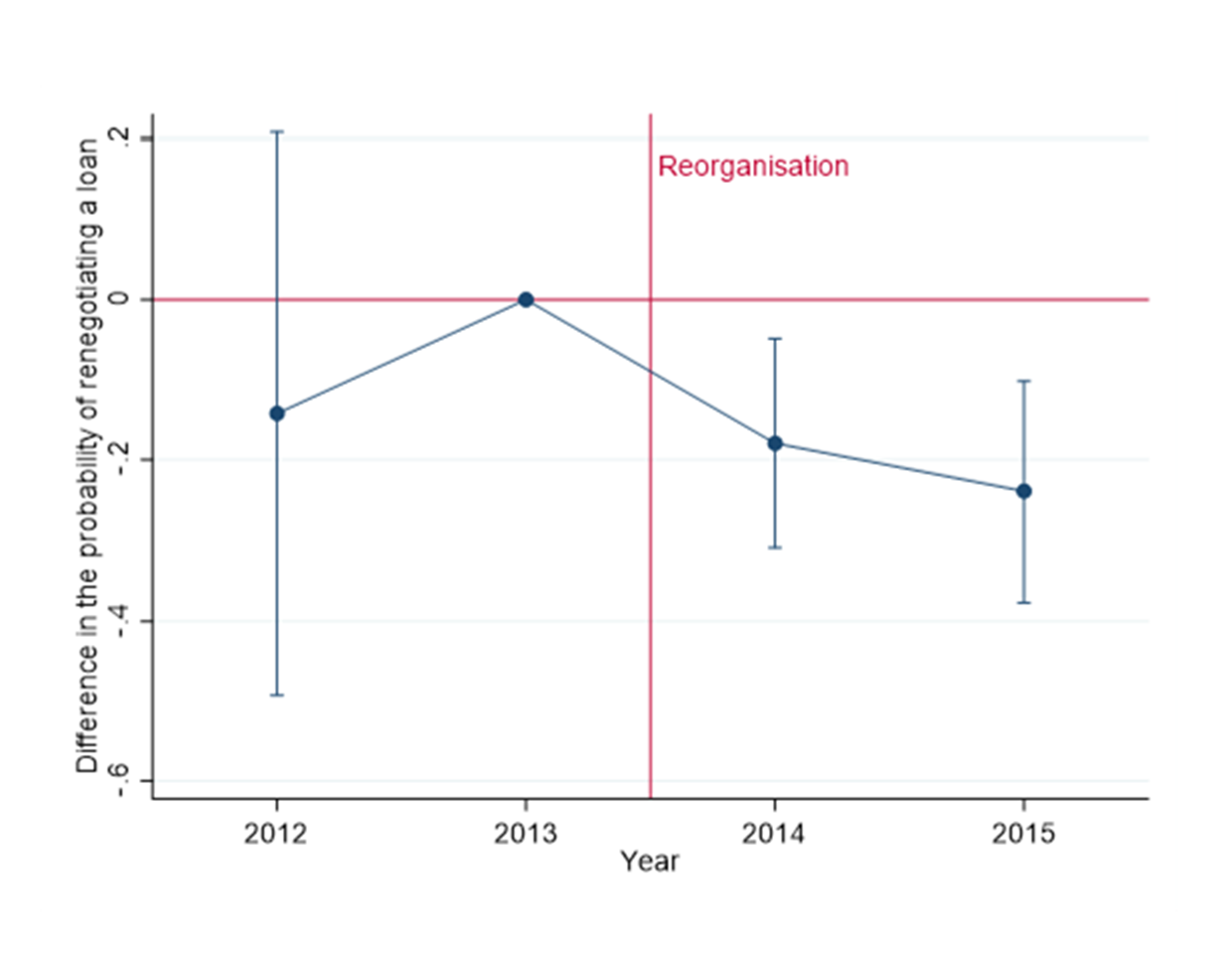

According to my results, firms assigned to a new loan officer were significantly less likely to renegotiate a loan. The empirical results show a statistically significant difference in the probability of these firms renegotiating a loan compared to firms with continuous relationships. In particular, the results imply a 49% probability of loan renegotiation for firms with an interrupted relationship, compared with a 59% probability for firms with a continuous relationship. Figure 1 presents the evolution of the effect over time. We observe that before the reorganisation (2012-13) there is no statistically significant difference between the two groups of firms when it comes to the probability of renegotiating a loan. After the reorganisation (2014-15), the probability of renegotiating a loan is lower for the firms with interrupted relationships. Moreover, this effect lasts for at least two years.

Figure 1

Effect of an interruption in the relationship between a loan officer and a firm on loan renegotiation relative to the year before the reorganisation (2013)

Source: Papoutsi (2021).

Notes: The y-axis shows the difference in the probability of renegotiating a loan (expressed in fractions) between the firms with interrupted relationships and firms with continuous relationships. The red vertical line shows the time of the reorganisation. The coefficients are obtained from a difference-in-difference regression of the renegotiation dummy on an indicator for interrupted relationships and on region and bank unit fixed effects. The bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals. The economic magnitude of the effect can be estimated in the following way: a loan is renegotiated on average with 59% probability and the plot shows that the fractional difference between firms with uninterrupted and interrupted relationships is 0.18 (vertical difference between the blue dots for 2014 and 2013). Thus, firms with interrupted relationships have approximately a 48% probability of renegotiating a loan.

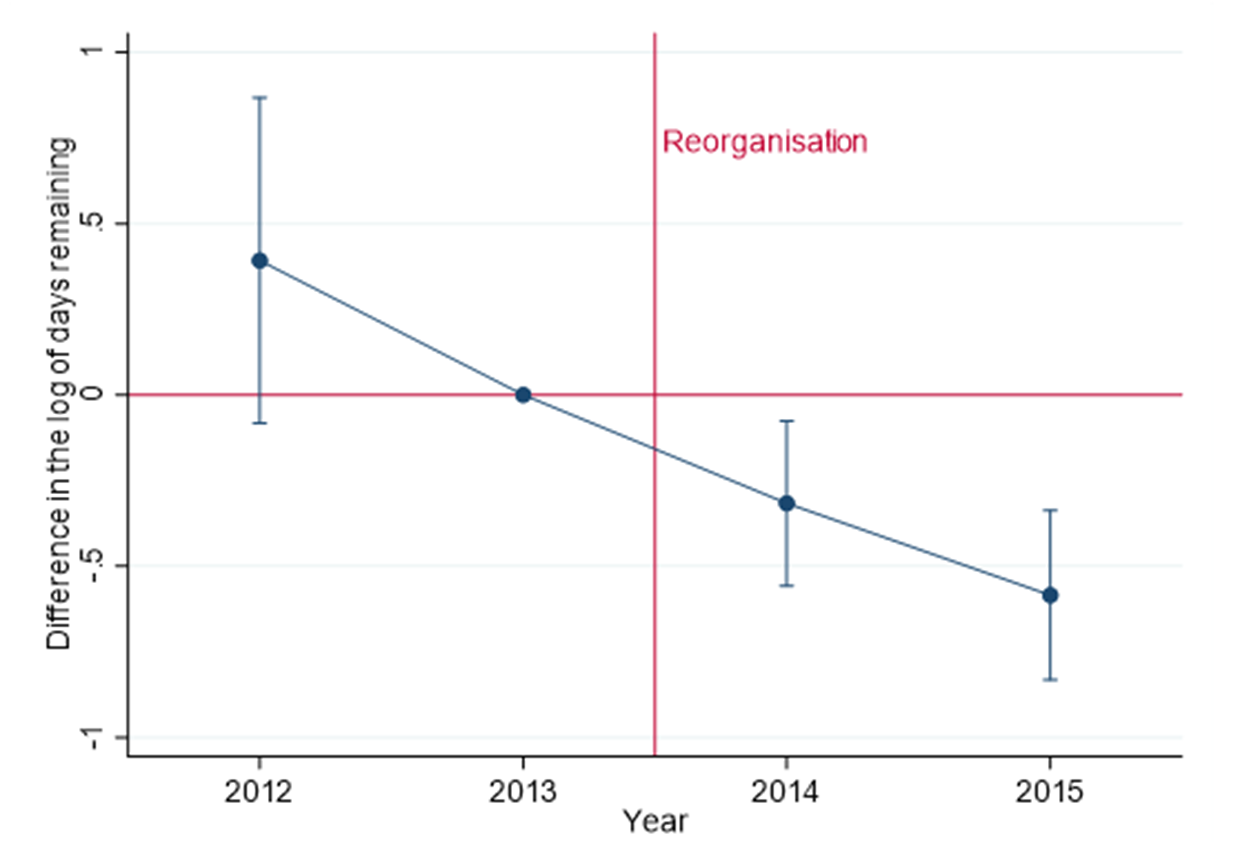

Moreover, when loans are renegotiated, the firms with interrupted loan officer relationships receive less beneficial terms and conditions on their renegotiated loans than firms with continuous relationships. Firms with interrupted relationships face higher interest rates and significantly shorter maturities, while being required to pledge collateral for an amount 65% higher than firms with continuous relationships. The economic magnitudes of the impact on loan maturity and collateral are significant as they correspond to a maturity approximately two years shorter and an additional €0.78 of collateral for each euro of loan amount. The plots below present the evolution of these results graphically. The difference in the loan terms appears in the first year after the interruption of the relationship and increases the following year.

Figure 2

Impact of interrupted relationships on renegotiated loans’ terms relative to the year before the reorganisation (2013)

Effect on interest rate

Effect on remaining days

Effect on collateral value

Source: Papoutsi (2021).

Notes: The y axis shows the average percentage difference on each of the loan terms between the firms with interrupted relationships and the firms with continuous relationships. The red vertical line shows the time of the reorganisation. The bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals. In panel (a), the dependent variable is the level of the interest rate. In panel (b), the dependent variable is the log of days remaining as a measure of loan maturity. In panel (c), the dependent variable is the log of collateral value. The estimated effects are obtained from a regression of the dependent variables on an interrupted relationship indicator and on region and bank-unit fixed effects. The economic magnitude of the effect on maturity is shown in panel (b) in the following way: a renegotiated loan receives on average a five-year maturity extension and the plot shows that the fractional difference between firms with uninterrupted and interrupted relationships is 0.3 (the vertical difference in the blue dots for 2014 and 2013). Thus, firms with interrupted relationship receive a maturity extension of approximately 3.5 years. The economic effect on the interest rate and on the collateral can be estimated accordingly.

Another finding of the study is that firms raise more equity and reduce their borrowing when the relationship with the loan officer is interrupted. A change in the capital structure indicates that firms cannot simply substitute lending from other banks without cost when the relationship with one bank is interrupted. Firms only partially substitute loans from other banks to make up for reducing the borrowing from the bank where its loan officer relationship was severed. This change in a firm’s sources of financing is likely to have material implications for the firm’s business model and investments, and consequently for the real economy.

The empirical results suggest that a stable relationship between a particular loan officer and a firm helps to alleviate debt overhang through the acquisition of soft information and that this mostly benefits the firms performing well. This conclusion can be drawn from several tests. First, we do not observe a difference in loan performance in the short run between firms with interrupted relationships and firms with continuous relationships. This means that the effects on the terms and conditions of renegotiated loans cannot be explained by firms performing worse economically. Second, one hypothesis to be examined is whether firms with continuous relationships receive better treatment due to evergreening. If this hypothesis were true, poorly performing firms would renegotiate more often and on better loan conditions than firms performing well, in order to prevent them defaulting on a loan payment. In contrast, the impact of an interrupted loan officer relationship on loan renegotiation is found to be stronger for firms with good repayment histories, high leverage, and positive growth in earnings.

Conclusions

The option to renegotiate loans is likely to gain hugely in significance following the COVID-19 outbreak and the subsequent crisis, as loan defaults rise during recession periods. This analysis shows that lending relationships have a significant positive effect on corporate loan renegotiation, mitigating the cost of distress for firms. Even though the analysis is not directly linked to the COVID-19 crisis, it provides strong evidence that continuous lending relationships help firms during default episodes. An uninterrupted relationship between a particular loan officer and a firm helps eliminate frictions that arise when loans are renegotiated. When a relationship is interrupted, the outcome of any renegotiation is less likely to be beneficial for the firm, and an efficient contract is less likely to be achieved.

The estimations presented are probably also representative of other European banks. The analysis draws on a novel dataset on corporate loans and bank reorganisation in Greece, as the uniqueness of the institutional setting combined with the data available allow us to accurately identify the causal effect on loan renegotiation of an interruption in the relationship between a loan officer and a firm. However, the results should be considered as relevant beyond the Greek banking sector. Several banks in the euro area have changed the organisational structure behind their loan officers during the last decade. This was sometimes due to a merger with another bank, and sometimes a cost reduction policy. The results therefore suggest that bank managers, supervisors, and resolution authorities need to be mindful of the potential costs of changing loan officers. For example, in a context of general stress, individual firms could experience interruptions to several different bank loan officer relationships. This in turn could have a significant effect on firms’ capital structure and borrowing capacity. These results clearly indicate net benefits for firms of stable loan officer relationships. Indeed, while no one is irreplaceable, when it comes to a firm’s relationship with a bank changing loan officer can be a big deal.

References

Cole, S., Kanz, M. and Klapper, L. (2015). “Incentivizing calculated risk-taking: Evidence from an experiment with commercial bank loan officers”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 70, pp. 537-575.

Drexler, A., and Schoar, A. (2014). “Do relationships matter? Evidence from loan officer turnover”, Management Science, Vol. 60, pp. 2722-2736.

Engelberg, J., Gao, P. and Parsons, C. (2012). “Friends with money”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 103, pp. 169-188.

Fisman, R., Paravisini, D. and Vig, V. (2017). “Cultural proximity and loan outcomes”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 107, pp. 457-492.

Haselmann, R., Schoenherr, D. and Vig, V. (2016). “Rent-seeking in elite networks”, SAFE Working Paper Series.

Hertzberg, A., Liberti, J. and Paravisini, D. (2010). “Information and incentives inside the firm: Evidence from loan officer rotation”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 65, pp. 795-828.

Karolyi, S. (2018). “Personal lending relationships”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 73, pp. 5-49.

Liberti, J., and Mian, A. (2009). “Estimating the effect of hierarchies on information use”, The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 22, pp. 4057-4090.

Papoutsi, M. (2021). “Lending relationships and loan renegotiation: Evidence from corporate loans”, ECB Working Paper series.

- This article was written by Melina Papoutsi (Senior Economist, Directorate General Research, European Central Bank). The author gratefully acknowledges the comments of Simone Manganelli, Alexander Popov, and Zoë Sprokel. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank or the Eurosystem.

- Related literature has shown that bank-specific governance policies have an effect on the moral hazard behaviour of a loan officer. Hertzberg, Liberti, and Paravisini (2010) present evidence that when a loan officer anticipates rotation, reports about a firm’s creditworthiness are more accurate and contain more bad news about the borrower’s repayment prospects. Cole, Kanz, and Klapper (2015) show that performance-based compensation leads to greater screening effort and more profitable lending decisions.

- This analysis is closely related to the literature that identifies the effects of relationships between bank employees and borrowers. These studies focus on how lending is influenced by factors such as cultural proximity (Fisman, Paravisini, and Vig, 2017), social connections (Haselmann, Schoenherr, and Vig, 2016), hierarchical and geographical distance (Liberti and Mian, 2009), the loan officer being on leave (Drexler and Schoar, 2014), strong interpersonal connections (Engelberg, Gao, and Parsons, 2012), or the interruption of a relationship caused by an executive’s death or retirement (Karolyi, 2018).